Lawyer Limelight: Ted Mirvis

By Katrina Dewey | January 22, 2017 | Lawyer Limelights, News & Features, Wachtell Lipton Features

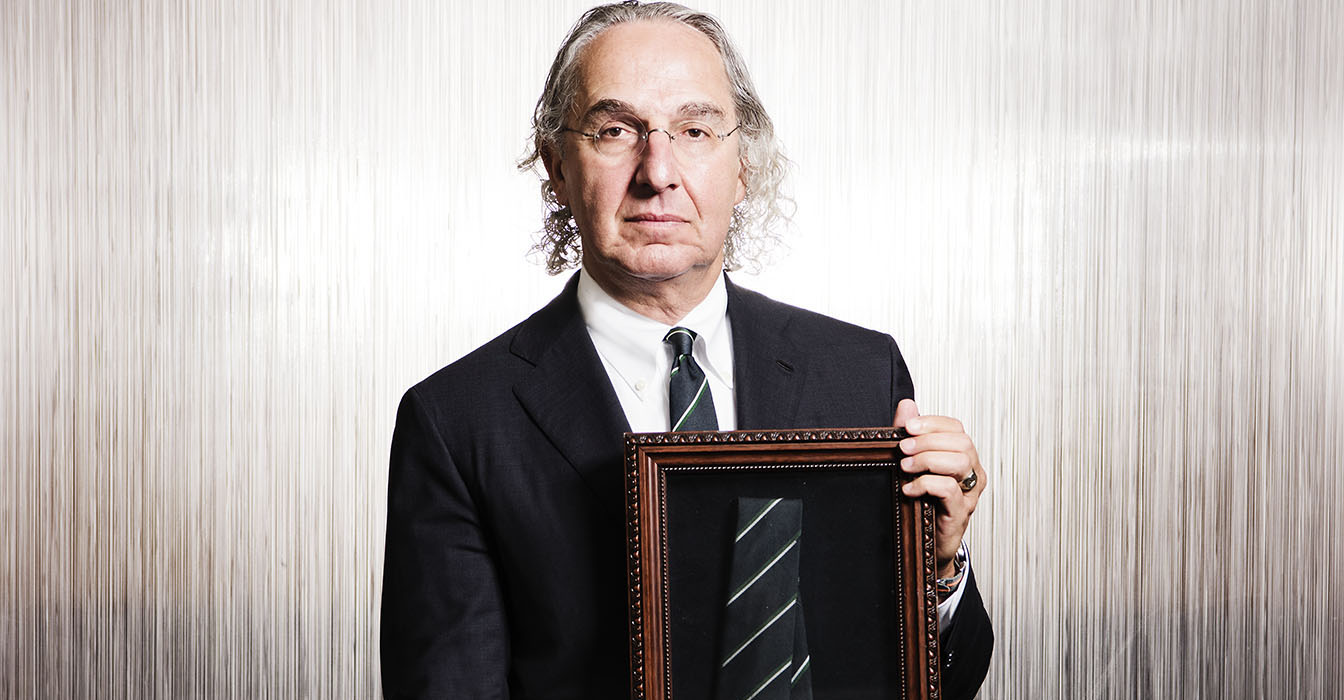

Photo by Laura Barisonzi.

Ted Mirvis tiptoed up the stairs to the attic in his family’s new home at 158 Algonquin Road in Hampton, Va. The inquisitive six-year old found boxes and could not resist the temptation to stealthily lift their edges and peer inside.

His newfound treasure confounded him. They were huge books! – in whose company he spent magical hours. After some time and pondering, he concluded they must be law books.

His father had been sent South from New York to be the rabbi in Hampton, so the young Mirvis reasoned the books were probably not his father’s religious texts.

Hmmm.

“Are you a lawyer?” he looked up one day and asked his mom. He knew she also worked as the accountant and buyer of her family’s clothing business, Sear’s Department Store, which catered to the large military presence in Hampton and around Norfolk, just across the Bay. “Yes,” Lena Sear Mirvis, told her son. She was also a lawyer, having read the law after graduating from Duke. In 1937, she took the bar and became one of the first women admitted in the Commonwealth of Virginia.

For those who know Mirvis, his pedigree is not surprising. He’s been called the greatest mind in corporate litigation, and his cases comprise a treatise on corporate governance battles. He’s the lawyer Bank of America turned to when they needed a mastermind to steer them through the financial collapse fallout. And, when the NASD turned its jaundiced eye toward Kenneth Langone’s firm, Invemed Associates, supposedly favoring certain of its clients with pieces of hot IPOs in the 1999-2000 craze, Marty Lipton reportedly told the Home Depot billionaire, “There’s only one person who can save you.”

And he did.

Lawdragon: There’s a mystique to becoming a partner at Wachtell. How did you join this firm?

Ted Mirvis: I’m the luckiest man on the face of the earth. When I joined Wachtell, no one at Harvard Law School had heard of Wachtell. It was 1976 and there was no Internet, no email, no American Lawyer. There was no information for students about law firms. So most of the people on law review with me assumed I had good grades but that I must have been convicted of a crime. They’d say, “What is that, a garment shop?”

But when I was a second year, Wachtell wrote to everyone on law review. And as I was opening the letter, another 2L walking by said, “That’s a great firm.” That night, I got a call from Nathan Lewin, a founder of Miller Cassidy, which was almost entirely Supreme Court clerks. I had worked with him at the National Center for Jewish Policy Studies one summer. And Lewin said Wachtell was a great firm – that I should sign up to see them.

Within the next 10 days, I was talking to my Mom, who came to New York once every season to buy fur coats for the family store from a guy named Katcher, who was the uncle of Richard Katcher, who had just left Simpson Thacher for Wachtell.

And then during my clerkship year, Judge Friendly called me into his chambers one day. He knew I wasn’t trying to get a U.S. Supreme Court clerkship after I completed my clerkship with him. And he asked, “Where are you going next year, Ted?” I didn’t have a real answer and I didn’t want to tell him I had a job with this firm no one’s heard of. He said, “What firm?” and I said, “It’s a small firm. They do a lot of securities work.” And he said, “WHAT’S THE NAME OF THE FIRM?” So I told him Wachtell. “Oh! That’s Marty Lipton’s firm. That’s a great firm.”

LD: I guess given Marty Lipton and Bernie Nussbaum, among others at the helm, it’s no huge surprise you became a corporate litigator. But how did you arrive at that rather than deals, and how did you become preeminent in corporate governance disputes?

TM: I didn’t set out to do anything. When I was asked if I was going to be a litigator or corporate lawyer, I’d say “I don’t know.” I was interviewing at some firm and said I didn’t know. And whoever was interviewing me said, “That’s not a good answer. You should say one or the other.” Civil procedure had been my favorite class in law school – I loved Paul Bator and David Shapiro – so from then on I said I wanted to be a litigator.

Then in the early 1980s, I’m a young whippersnapper and I’ve made partner. I get a call at 8 a.m. from a partner who says, “Can you fill in for me around the corner at 49th and Park? I’m on a panel on takeover litigation with [Delaware Supreme Court] Justice [Andrew] Moore?”

The answer is “Yes!!” The Unocal takeover case was starting and they’re talking about a director’s duty of care and Smith v. Van Gorkom. The panel is Justice Moore, the general counsel of the SEC, Gil Sparks from Morris Nichols and Steve Rothschild from Skadden, the number one Delaware litigator – and me. There was literally no law from the Delaware courts except stray sentences about the proper role of directors in fighting a tender offer.

We were not involved in Unocal. So I said, “If you step back and think about the Delaware statute, to approve a merger you need approval of the board of directors first. Shareholders cannot vote to approve a merger unless the board of directors has approved it. There is no such thing as a hostile merger. I don’t see why tender offers should be any different. Why should the board of directors not have that same power when it comes to whether a tender offer should go forward?”

And Drew Moore looked over at me and said, “That’s a really good point.” The Unocal decision came out not long after, and it was the first in Delaware to recognize the power of the board of directors to stop hostile tender offers. And the pivotal point is that under Delaware Corporate Law section 251 directors are the gatekeepers of mergers, so therefore under section 141(a), they should have the same power with respect to tender offers.

LD: That must have felt pretty cool. Is it safe to assume that experience had an impact on your focus on scholarly writing and speaking on panels about corporate governance, as you do regularly at the Tulane Corporate Law Institute?

TM: Absolutely. One of the things I’m most proud of is the exclusive forum bylaw, which I first proposed on a panel. I gave a talk on “ABC, Anywhere But Chancery.” The plaintiff corporate securities bar had begun to say they were not going to sue in Chancery anymore and instead were going to bring their cases in other jurisdictions that were less sophisticated and where their cases had greater settlement value.

I thought that was a terrible thing for the system. So I asked “Why can’t a corporation adopt by charter a provision that says a charter is a contract so it can have choice of forum provisions.” The late Frank Balotti of Richards Layton was sitting next to me and he said, “What are you saying?” And I said, “I think a corporation can put in its charter that all shareholder claims have to be brought only in the courts of Delaware.” He looked at me in front of 100 people and said, “That’s the most ridiculous thing I ever heard.” But people began to adopt it, and eventually in the Chevron case [now Delaware Chief Justice Leo] Strine approved it.

There are now more companies that have the Mirvis bylaw than the poison pill. Thousands of companies have adopted the Delaware exclusive forum provision.

LD: What other cases have you been particularly proud of over the years?

TM: One of the best oral arguments I ever made was in 1982 in front of Judge Walter Stapleton in Delaware federal District Court. We represented City Service trying to fight off a hostile bid from Mesa and T. Boone Pickens. I lost.

What I remember most is when I got back to the office around 8 p.m. I got a phone call, and I didn’t know who it was. The guy starts talking to me and I figure out it’s an arbitrageur. So I said, “I’m not going to talk to you.” But what he said was, “We figured since they sent such a young guy to argue, City Service must have a white knight and they don’t care about the motion; they’re going to sell anyway. But we were all in the courtroom and when we saw what a good job you did, we thought maybe you don’t have a white knight.”

One of my most fun victories was winning both federal and state court motions to dismiss for Salomon Brothers when they were sued by [Vincent Murphy] one of the original founders for supposedly breaching fiduciary duties to him and the other former partners after the firm merged with Philipp Brothers. After I got the federal case dismissed by Southern District of New York Judge Morris Lasker, the plaintiffs hired Arthur Liman and sued in state court. We won the state court equivalent of a motion to dismiss. Then, in my first appellate argument ever, I go down by myself and Arthur Liman is there with this huge Paul Weiss team. He gets up and says to the judges, “Not only should you reverse, you should grant judgment in our favor.”

And I’m thinking, “It’s one thing to go home and say the dismissal was reversed, but it’s another to say, ‘We just lost the case.’” I argued for 25 minutes and on Dec. 13, 1988, we got the decision. “Judgment is hereby affirmed. 5-0. Argued by Arthur Liman and Theodore Mirvis.”

LD: And there are a slew of other headliner cases, including representing Airgas in the Air Products takeover.

TM: Nobody thought we were right in our battle to defeat the Air Products hostile takeover. I thought I understood the bylaw issue very well, and if you can be passionate about a legal issue, I was passionate about that one. My longest oral argument was for Newmont Mining in 1987 fighting a hostile takeover bid from Pickens. I was not feeling well, threw up twice on the way down. But my argument went over two hours and I was in the zone. We won.

One of the longest-running matters lasted nearly 10 years. We represented MCA in connection with the Matsushita acquisition in a very complicated stockholder claim. On behalf of MCA shareholders, they claimed that MCA head Lew Wasserman had a sweetheart deal in the sale, and we reached a settlement of the Delaware state court claim. That was challenged ultimately in the U.S. Supreme Court, where Barry Ostrager, then of Simpson Thacher, argued and won a decision that state court settlements, including in the Court of Chancery, can as a constitutional matter release federal claims arising from the same facts, including claims within the exclusive jurisdiction of the federal courts. That was a critical doctrinal point that allowed deal litigation to proceed in Chancery. I must have written 30 briefs in that case.

LD: One of the more intriguing things about you is that you are by no means just another law firm partner, whatever that means. Everyone is always interested in your long hair, and I hear you even have a neck-tie made after you now.

TM: When I defended Ken Langone, I told him that I would not cut my hair until he was totally vindicated. I have no idea why I said that. That was in 2003. And even though the case against him was completely dismissed in 2006, he asked me to keep to my promise even afterwards. So I have.

And the tie story is funny. I had a lucky tie that I’d worn at every oral argument. It was very frayed and I decided to retire it after the win in the Invemed matter. And so Sabrina Ursaner at Wachtell, who had worked on the case with me, claimed she could have it replicated. But apparently she told the tie maker it had to be EXACTLY the same as the old tie. So when they sent back the new one, it had the same frays and wear as the old one. And now Turnbull & Asser are marketing a tie with fray marks based on her obsession with detail.

LD: It’s also important that people know of your close ties to and family in Israel. Can you talk a bit about that?

TM: Sure. My dad spent the last 20 years of his life in Jerusalem after he retired from the rabbinate, and my daughter lives there now with her husband and seven of my grandkids. So my wife and I visit as often as we can, and I have been able to teach some classes at Hebrew University law school and also participate on CLE -type panels with judges of the new Tel Aviv Economic Division of the District Court, a kind of Israeli Chancery Court.

LD: And what’s the Yom Kippur Open?

TM: Oh, that’s a small golf outing I started 20 years ago. We play every year around Yom Kippur with about 20 friends. It’s just a funny name, and we raise some funds for the NYU Langone Medical Center. The YKO is also a national sponsor of the U.S. tour of the Israeli Philharmonic Orchestra. It’s a great group of people.