Attorneys in Sept. 11 Case Battle Over Adequacy of Bleak Torture Descriptions

By John Ryan | November 15, 2018 | Guantanamo Bay, News & Features

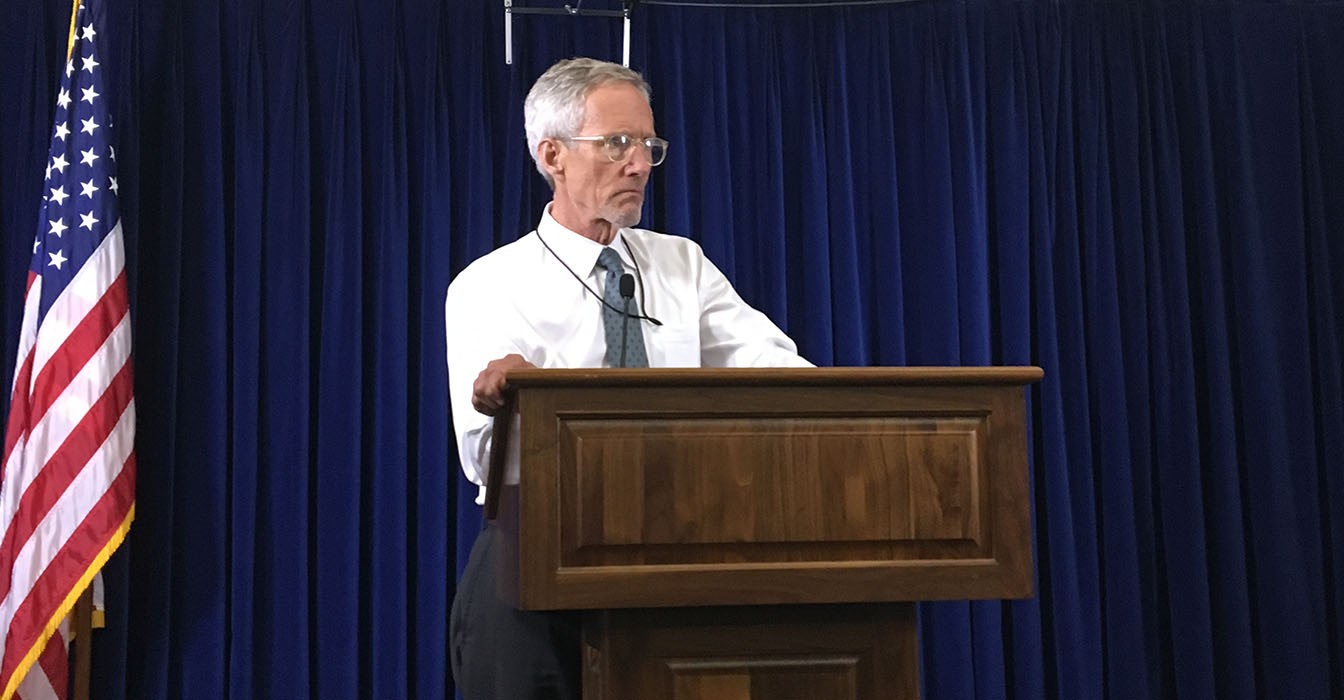

David Nevin is the lead defense attorney for Khalid Shaikh Mohammad.

Guantanamo Naval Base, Cuba – Prosecutors and defense attorneys in the Sept. 11 case argued on Thursday over what constitutes a “rich and vivid” account of the abuse the five defendants suffered at CIA black sites before their arrival at Guantanamo Bay in September 2006.

As in every phase of the long history of pretrial litigation over the CIA program, the two sides differed sharply in their assessments and even its appropriate terminology: What the government summarizes as rectal hydration, the defense calls rape.

The tense and uncomfortable exchanges came as the prosecution team asked the new judge, Marine Col. Keith Parrella, to reconsider the order of his predecessor barring the government from using any statements the defendants made to FBI interrogators at Guantanamo in early 2007 – statements prosecutor Jeffrey Groharing said was some of the most “critical” evidence in the case.

In one of his final rulings, the prior judge, Army Col. James Pohl, held in August that the government’s restrictions on defense investigations into the CIA program would inhibit the defense teams' ability to make the case that the FBI statements were tainted by past torture. He decided to exclude the FBI statements – even before the defense teams had filed their long-planned suppression motions – concluding they could never fairly litigate the issue.

“They won the lottery without ever buying a ticket,” Groharing said of the defense.

The prosecutor attacked Pohl’s ruling for the better part of 80 minutes Thursday morning, calling it a “manifest injustice.” Pohl's decision came in response to the government’s request for a protective order prohibiting the defense teams from independently contacting any current or former CIA personnel who participated in the black site interrogations. In his ruling, Pohl signed off on the restrictions but decided they would prevent the teams from developing “rich and vivid” accounts of CIA abuse.

Groharing portrayed the order as a strange, out-of-the-blue and premature sanction against the government that completely undercut dozens of Pohl’s earlier decisions that approved the black-site evidence provided to the defense teams. Most of the thousands of pages of evidence about the CIA interrogations are substitutions and summaries of original evidence that Pohl concluded gave the defense teams “substantially the same ability” to defend their clients as if they had the original materials.

Groharing read from selections of the summary evidence to support his argument that the defense teams were “well-armed” to offer very vivid accounts. One summary of a CIA cable described the accused plot mastermind, Khalid Shaikh Mohammad, being stripped and shaved before subjected to slapping, stress positions and water dousing. Mohammad moaned, cried and chanted at various times and was eventually “rectally hydrated” after refusing to eat or drink.

“Mohammad clearly hated the procedure,” Groharing said, reading from the summarized cable, as the defendant sat 20 feet to his left.

Groharing also read statements that CIA personnel gave to the agency’s Office of Inspector General, which investigated the program. One agent said she was “shocked” to see Mohammad hanging from a bar; she said she was “ashamed” for participating in the “nightmare” program. Another unnamed individual described a black site as something “teenage boys” would come up with if deciding to build a horrible prison. Yet another described a black site as a “dungeon” that was effective in establishing detainee expectations.

The defense teams could combine this discovery with open-source documents and the recollections of their clients, Groharing claimed. He said the government had “no intention” of disputing details of past abuse and would even stipulate to lengthy and graphic accounts developed by defense teams, so long as they were “tethered to reality.”

Finally, he said, the defense teams can make requests to interview CIA personnel who are identified in the government’s summaries by codes. These individuals can voluntarily agree to be interviewed under protocols that keep their identities hidden.

James Connell, the lead attorney for Mohammad’s nephew, Ammar al Baluchi, who was also in court Thursday, said that Pohl was right to conclude that the defense teams were unfairly hindered in building vivid accounts. He countered Groharing’s summaries with a list of missing details: what the slaps or Mohammad’s cries sounded like; how he looked when hanging in stress position; whether steam rose from his naked body when being doused with water in a cold room.

His voice nearly breaking from emotion, Connell said those are the details needed to recreate the feel of a dungeon built by teenage boys.

In this instance, Connell said he would want to ask the CIA interrogator what it feels like to “drown” or to “anally rape” a person.

Parrella wondered whether accounts generated by the defense teams and stipulated to by the government could ever suffice. Connell said that was an impossible task. He cited a recent a news article about how the CIA considered using a truth serum on detainees.

“My imagination fails when it comes to how badly these men were treated,” he said.

David Nevin, the lead attorney for Mohammad, said that Groharing’s summary of about a page or so in length was meant to document interrogation sessions lasting 15 hours.

“You think to yourself, ‘What’s not there?” Nevin said.

He added that just the mention of rectal hydration raised several follow-up questions, such as whether he was face down or on his back, or whether lubrication was used.

“Did someone hold his legs apart?” Nevin asked.

The defense lawyers also challenged Groharing’s claim that Pohl’s ruling came out of nowhere, or that it contradicted his earlier approvals of summarized evidence. In fact, they argued, Pohl had been signaling to all the parties over the past several months of increasingly contentious litigating that defense lawyers would need to question CIA witnesses to gather more details.

The attorneys contended that the prosecution motion did not meet the standards for reconsideration and that the judge should show deference to Pohl’s reasoning and conclusions, which were based on years of exceedingly complex and document-intensive litigation.

Nevin said that the summarized discovery provided to the defense was meant to be a starting point, not the end of the road for any investigations. He said that a failure to completely investigate past torture would make any defense lawyer a “walking” constitutional violation of a defendant’s right to effective assistance of counsel.

In his argument, Connell said that the defense teams also lost out in Pohl’s August order, which ratified the investigative restrictions. In addition, Pohl concluded in the ruling that the prohibitions did not unfairly effect the teams' ability to litigate mitigation in the event of any convictions. If Pohl had reasoned differently, he likely would have removed the death penalty as a sentencing option, Connell argued.

Connell asked Parrella to revisit the mitigation issue if he decides to reconsider Pohl’s ruling.

If Parrella does not rescind Pohl’s exclusion of the FBI statements, the government will likely appeal the ruling to the military commissions appellate court, a move that could delay the case for months. Pohl did not set a trial date before departing.

The bleak content of Thursday’s session put in stark terms the sprawling mess that the disbanded CIA program has created for the prosecution, the defense teams, Pohl and now Parrella, who is presiding over just his second session in a case that dates to the May 2012 arraignment. This week’s session is the 32nd pretrial session in the case; the next session is scheduled for Dec. 3-7.

About the author: John Ryan (john@lawdragon.com) is a co-founder and the Editor-in-Chief of Lawdragon Inc., where he oversees all web and magazine content and provides regular coverage of the military commissions at Guantanamo Bay. When he’s not at GTMO, John is based in Brooklyn. He has covered complex legal issues for 20 years and has won multiple awards for his journalism. View our staff page.