Lawyer Limelight: Leopold Sher and James Garner 10 Years After Hurricane Katrina

By Katrina Dewey | August 28, 2015 | Lawyer Limelights, 2015 Magazine Limelights, News & Features

Photo of James Garner (left) and Leopold Sher by Sara Essex Bradley.

Leopold Sher and James Garner have been through hell and high water together since leaving their old firm to start Sher Garner in 1999. But never was the water as high as on August 29, 2005. That, of course, was the day the levees broke in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

We sat down to talk with them in August, as the 10th anniversary of the disaster approached. By some accounts, the city has lost hundreds of lawyers in the 10 years since. But in that decade, Sher Garner has emerged stronger than ever in no small part because of a decision Sher and Garner made “in 60 seconds” to represent the city’s institutions against certain insurers in hopes of saving the city.

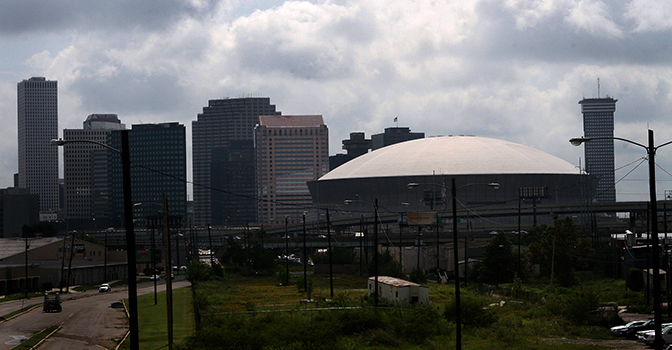

We’re sitting in their offices on Poydras Street, just blocks from the Superdome, where third-world scenes of devastation and misery played out. Outside, it’s humid of course, and there’s a sense that New Orleans is back in business. The Superdome is now the Mercedes-Benz Superdome and the Central Business District is more vibrant and bustling than ever.

The journey through those days, and the decade since, has been one of extraordinary determination by many New Orleans law firms, including Sher Garner. Their mission was nothing less than to help New Orleans survive by getting its critical institutions back in business – and helping one very special client while they were at it.

Lawdragon: Take me back to the days before Hurricane Katrina hit. What was going on with you both and the firm?

James Garner: I was sitting here on August 27. It was a Saturday and I was in my office with Chris Chocheles getting ready for a trial. I have a big TV in my office and we were watching as the hurricane was getting ready to hit Pensacola.

Lee Sher: I wasn’t here. On Sunday afternoon before the storm hit, my wife, Karen, and I were in the process of taking our daughter, Samantha, to the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia for freshman move-in and we were on the last plane they let fly out of New Orleans before shutting the airport down for the hurricane.

JG: My wife, Tracie, called around 2 p.m. and said we had to move. So we closed the doors and moved the computers into the conference rooms, away from the outside windows. I got home and we evacuated Sunday morning at 6 a.m. for the eight-hour drive to Baton Rouge. A drive that normally takes about an hour-and-a-half.

I was on the phone with Lee, who was in Philly, and was in touch with his 89-year old father, Joseph, who stayed in his home on Broadway Street near Tulane. We made it to Baton Rouge, to my grandmother’s house, which had no power. My uncle had a generator, so we got enough power to see what was happening, and I could call Lee.

LS: The day after the levees broke, the ground-floor basement of the apartment building where I grew up flooded with five feet of water. And my Dad was in his apartment on the first floor right above.

LD: How did you balance this – the fear for your father, and keep the presence of mind to get your firm functioning quickly in Baton Rouge?

JG: On Monday night, the levees had broken, and we’re seeing all the Google images. We were at my aunt’s house in Baton Rouge, and she’s a realtor. I realized we had to move. So by Tuesday, my aunt was grabbing up every rental, from Zachary to Prairieville. By that Wednesday, we had rented 30 houses in the Baton Rouge area.

Then on Wednesday, I hooked up with our partner Rick Richter, who had evacuated to St. Francisville. Rick, dressed in Jimmy Buffet fashion, picked me up, and we drove around to find rental space for the office and ended up on Essen Lane in Baton Rouge. All of our people had been in 30,000+ square-feet of space in New Orleans, and now we had 10,000 square-feet in Baton Rouge. It was very cozy.

That week, we had telephones and computers installed and were able to open the next week, the day after Labor Day.

We obtained supplies for everyone – from underwear to soap, and took folks to the Piccadilly Cafeteria across the street. Lee got back Sunday night before Labor Day and helped us put our daughter Margaret’s baby bed together.

We were going to Best Buy, Target, and Conn’s furniture for televisions, supplies, furniture and appliances. Everything was happening in such a compressed period.

LD: How were you feeling during that week?

JG: In the middle of it, you’re just reacting. Adrenalin keeps you from being distracted. We had 85 employees to take care of.

LS: And I was trying to get my father out of New Orleans, and keep everyone’s spirits up. It was the beginning of the school year, so we also had to get our people's kids into new schools in and around the Baton Rouge area. You need to remember that New Orleans was under water and closed down. Our team in Baton Rouge found clothing, housing, food, and supplies for our people, and schools for their kids. We told everybody we’d take care of their families, their insurance claims, and that they’d continue to get paid. And nobody missed a paycheck. Ever. And that was whether they could work or not.

Between the Sunday before Katrina hit and the day after the storm passed, the population of Baton Rouge nearly doubled with all of us evacuees from the New Orleans area. So it’s not like you had your pick of the litter of housing, office space, supplies, clothing, food and other normal stuff we take for granted. Our guys on the ground in Baton Rouge were running around like crazy trying to secure all those things for our people while everyone else was trying to do the same thing.

JG: Needing to house my parents, Adrian and Mary Ann, and my wife, Tracie, and our three children, Ethan, Caitlin and Margaret, I bought a house sight unseen from a bank on Perkins Road. The bank lent me the money with no backup, no documents and no signatures.

LD: Lee, tell me a bit more about your dad’s situation. I remember he is a Holocaust survivor. It’s unbelievable he also lived through Katrina.

LS: Three weeks before Katrina, my dad had a heart attack. He’s a strong man – not physically, he’s slight, about 5’3” – but considering all that he has been through in his life, he’s very strong. My wife, Karen, insisted on taking him on the trip with us to move our daughter into Penn in Philadelphia, but he would not go no matter how much my wife begged and pleaded with him. He said the rigors of traveling would be harder on him considering his then condition than remaining in his comfortable apartment. So he stayed. He said, “I’ve been through hurricane after hurricane. I will be fine."

When the city flooded, my dad got stranded. We appealed to the governor's office, the military, emergency-preparedness groups, social and religious service agencies, and people we knew in high places. And they all promised to go pick him up. But there was too much water and he was not a priority.

So, by the Thursday after the hurricane, he’d had no running water, no fresh food, no working bathrooms. He was doing OK, however, as he regularly told us and our daughter, Rose, who was calling him several times a day from Los Angeles, where she was safely ensconced in her third year of college at USC. Coincidentally, the week before the hurricane hit, Karen had arranged for “Lifeline” to be installed at my dad’s apartment and the installer must have fortified his telephone landline so it continued to work - not always, but intermittently. There might have been a handful of working phones in the city, and my dad's rotary phone was one of them!

LD: This is such a hard conversation to have, even 10 years later. What happened to him?

LS: While stranded in Philadelphia, we hadn’t slept in three days trying to get someone to rescue my dad. We were speaking with him regularly much to our relief and comfort. About noon on Thursday he called to tell us he was still doing well but added: “Look, there’s a guy here who wants to rescue me. Should I go?”

And we later learned the story of this “guy.” My dad and the three other people stranded in the same apartment building with my dad were on their front porches on that Thursday morning when they saw a young looking man walking through chest-deep water down Broadway Street in front of my dad’s apartment building. They called to the guy and told him that if he wanted to take a respite from walking in the deep water that he should come up and join them. And the guy shouted back “I don’t need rest. I want to save people.” That “guy” was just a solo Good Samaritan unconnected to any group or organization, an angel. His name, we later learned, is Juan Parke.

While I was on the phone with my dad that Thursday at noon, I thought it might be the last time I would ever talk to him. I told my dad to go with the man. I explained to him that everyone in the world had promised us they’d rescue him and nobody did.

I asked my dad how the man was planning on rescuing them. My dad told us that a skiff that had been tied to a metal roof of a garage at the back of their apartment building for the last 40 or 50 years had blown off in the storm, and it was just bobbing in the flood waters. One of the others in the building had seen the skiff in the water and directed Mr. Parke to the skiff. But the skiff only fit two people. So Mr. Parke used the skiff to rescue the four people in the apartment building one by one and took them to dry land at Loyola University on St. Charles Avenue - one of the rare spots in the city that was dry.

Incidentally, one of the four people in the apartment building with my dad was a retired Loyola ballet teacher who had parked her car at Loyola in its parking deck. My dad and the others were able to get in that car and they made their way to the Mississippi River Bridge through downed trees, power poles and other debris. At the crown of the bridge there were thousands of stranded, desperate people who had no place to go because the city was flooded. But they managed to get their car across the bridge and through that crowd and they drove to Baton Rouge where my dad was able to connect with my brother, who had that morning driven from his home in Dallas with the hope of helping to rescue my dad from there.

And Juan Parke? He went on to use that same skiff to rescue 20 other stranded people!

LD: There were so many heroic and so many tragic stories from those days.

JG: We had another one – another great client of ours, Enterprise Rental Car. They got us rental cars – 24-foot trucks. Toward the end of the next week – about 10 days after, once the water subsided – a group of our partners came and got into the building, grabbed computers and phones and took them all to Baton Rouge.

And then the phones started ringing. Children’s Hospital, Touro Hospital, individuals. They all needed help and we were available because we were up and back in business. This was around the time when people started writing articles about whether New Orleans should even be rebuilt! And Touro was shut down with $100 million in damage. Liberty Bank, the World Trade Center, Xavier and Dillard Universities, Canal Place. Everybody needed help.

LD: Did you have any qualms about suing insurers? After all your firm was only six-years old when the hurricane hit and you had a thriving commercial litigation and business practice.

JG: It was a fork in the road. We had been and generally are an hourly law firm – a defense firm doing insurance defense work. Most hourly defense lawyers didn’t want to sue insurance companies. And that decision has cost us some work. Some of our insurer clients certainly understood that we had no choice but to rebuild our homes and those of our families. We had an obligation to our City to help it rebuild and come back to life. We owe a great debt of gratitude to those insurer clients who understood and continue to use us until this day. Others didn’t understand. We could not in good conscience not take care of our families and New Orleans institutions.

And our will to stand with our families and City took us to the Louisiana Supreme Court. The case is Joseph Sher v. Lafayette Insurance Company - the named plaintiff is Lee’s father and involves the house that Lee grew up in at 1410 Broadway Street, a few blocks from our alma mater, Tulane University

Lee’s dad is a core part of this whole story, from getting him out to going to the Supreme Court where his bad-faith verdict against Lafayette was upheld. Lee’s dad is a modern-day hero. 89-years old at the time, he survived the Nazi concentration and work camps, and watched his family members die in the ghettos of Poland. After the war he and Lee’s mother, Rachel, traveled to New Orleans and landed at Poland Avenue at the Port of Embarkation on the Industrial Canal in the upper Ninth Ward of New Orleans. Lee was born in New Orleans and their family of four, including Lee’s older brother, Martin, put down their New Orleans roots. The family rode out Hurricane Betsy in 1965 at their apartment at 1410 Broadway and his dad, Joe, decided to do the same in Katrina.

Despite the evidence that water was wind driven through the windows, walls and roof, Lafayette Insurance Company refused to pay Lee’s dad’s claim, with the defense that the home was in poor shape. Fortunately for us, Lafayette’s underwriting file had notes about how well maintained the home was and the jury took very little time to award damages and find Lafayette in bad faith.

The insurance litigation raised our firm’s profile, but this wasn’t really about a business decision. We were making a decision to protect family, friends and our City. We are first and foremost New Orleanians. We dedicated ourselves to rebuilding the City, helping its institutions, our employees and one another. And we made that decision knowing there would be effects.

LS: We were sitting in our Essen Lane (Baton Rouge) office when a high-profile real estate developer client called. He was ready to throw in the towel and give up on New Orleans. We told him to buck up. We were confident New Orleans was going to come back behind leadership like the kind he would provide and we would be there for him to help however we could.

At that moment right after talking to our developer client, we felt we were at the fork in the road, asking ourselves and each other whether we should go with our heads and represent those certain insurance companies calling us for help, or whether we should go with our hearts and assist New Orleans in its return by helping our families, businesses, charities and core institutions that needed to come back or the City could be crippled forever.

And we went with our hearts. We agreed to handle the developer’s huge claim. We’re both natives to this area and both of us sustained serious water damage to our homes. We looked inward and told ourselves that we’ve got one chance. We’ve got to help Touro Infirmary, Children’s Hospital and Xavier and Dillard Universities. We must help the mom and pops, the grocery stores, the apartment complexes, the shopping centers and all others get rebuilt and re-opened. The City would not come back without healthcare, without schools, without banks, without living accomodations and without retail. We gotta help Liberty Bank because the city won’t be here if someone doesn’t help finance its rebuilding. We have to help our friends and families who won’t come back without help.

LD: How long did it take you to make that decision?

JG: We made it at the speed of light. We asked what it would take for this City to reopen – for it to establish its own economic and critical mass to come back. This decision was based on everything we grew up thinking; it was our own core values.

What comes out in you in those circumstances is who you are. We’re real people and these were real people and real institutions. It’s like Tom Cruise’s line in the movie Top Gun – when you’re up there, you have to react, not think. On August 30, 2005, we needed to react. There was little time to think. As a lawyer you want to think, but in this situation we needed to react. We needed to do something positively, quickly and constructively.

JG: That’s right. We reacted. Our discussions were limited to 60 seconds. We need to rent houses. What else? We worked 24 hours a day for three months. My oldest was 8 and my youngest 2, and we didn’t see our families. My wife was Trojan handling family matters while I was with Lee focusing on firm matters. We were fighting for our culture and home. Because we were irritated when people said let the City go into the Gulf. It was gut wrenching for people to say that the Saints and Hornets (now Pelicans) would leave. We said hell no. We were going to participate in the rebuilding of a great American city, our neighborhoods and our lives. There was gravity of who we were representing and what we were doing.

LS: We were doing great as a firm before Katrina hit. But it’s sort of what adversity does in catapulting you into another range and level. Post Katrina, our practice notched up to another level. All the big firms in town were representing insurance companies or afraid to do anything for fear of the repercussions.

And we felt there had to be some group of lawyers out there who could handle and pursue hurricane claims of all types and sizes - whether those claims were for $100 million, $250 million, $10 million, $100,000 or $5,000 – that had credibility, ability, drive, competence and excellence and, most importantly, a dedication to family and community. That we did it opened opportunities for us to become equal to the major firms that had longer track records and higher profiles.

When people meet me today they assume I am the child of the founder of our firm, and that our credibility and firm are ancient and that we’ve been around for generations. They don’t realize we are only 16-years old as a firm. Because of the support and confidence of our clients, we’ve established ourselves as an institution, though we don’t have hundreds of lawyers. But in terms of who’s recognized as players in town, I think that we are seen in that group. And to this day I can’t tell you whether it was our Katrina experience or my dad’s case that got us there. It might have happened anyway.

What we do know is Katrina hit and where we are now is what emerged after.

JG: It all comes back to building for the future. Sticking to our values, supporting our neighbors and our friends and the City of New Orleans. You need your friends when you are down. Everyone has friends when you’re successful. We put ourselves, our family, Martha Curtis’ mother, Lee’s dad, my parents, and our institutions first.

An Irish Catholic Brother at my high school in the Lower Ninth Ward once taught me, “Maturity is giving up a present good for a future good.” We focused on the future, building and investing in it. When I stood up at the United States Fifth Circuit for Xavier University, it was me versus lots of insurance lawyers. And the community remembers that. Even in the law business, the mechanics are Newtonian: every action has an opposite and equal reaction.

LS: And it’s really just our essence. We endured through Katrina and arrived where we are today because of our core values based on sticking together as a big family of decent people who want to practice law together to best serve our clients.

JG: A core value of the firm is the “being in the military, and in a foxhole” test. It’s trite but the truth. You can’t have someone guarding your back who’s going to stab you in the back. We wanted to make sure we would have the time to take care of each other and our families. We have to deal with lobbyists, politicians, landlords, judges, and opposing counsel. That’s enough to handle without fighting internally.

Unselfish players make it to the Hall of Fame, and there are not many show boaters in the Hall. Are they bad people? Probably not. But our philosophy is to be unselfish; we do not say 'my client'; we say 'our client'. We want the team player.

LD: Let’s talk about when you established the firm. It was 1999 and you had both been partners at another firm, one of New Orleans’ largest. Lee, you had been there for 25 years, and Jim, you had been for 10 years. Why did you decide to leave?

LS: We left with 25 people including us. All 25 started their careers at our former firm.

JG: There were 95 at that firm when I joined.

LS: And when I was a law clerk at the other firm I was a full-time law student in the morning and working every afternoon doing everything the firm needed me to do from cleaning up the break room, drafting pleadings and memos, making copies, doing court runs, interviewing witnesses – you name it. And Jim and all 24 of the others who joined us had the same experience. They were inculcated with the culture established by the founders of that firm. Over time, with the growth of the firm and particularly in the opening of the branch offices, a little of the culture began to change.

Also, the founders of that firm who established that culture and of whom we were disciples all died young. When they started the firm, they were energetic, creative, different, exciting, driven and dedicated professionals in sort of the newfangled way at the time, which was 1974.

There came a time after the death of the founders that the culture began to change and become diluted. With the regionalization of the firm also came further culture change. There is no one way to practice law which is right or wrong. But when you start bringing in new lateral lawyers to the firm you didn’t grow up with professionally who have a different way of looking at the firm, things change. Grains of sand in an oyster can make a beautiful pearl, but this kind of irritation, friction and sand introduced by new lawyers in a law firm may not be best for all. We don’t know what sparked it, but we all stepped back simultaneously and asked ourselves and each other, “Is this the culture we were trained under and bought into? Do we want to spend the rest of our careers in a changed culture?” We decided we didn’t want to.

We didn’t leave over a power struggle. The only question each one of us asked ourselves was: How do you want to spend most of your day and all of your professional life? What should be your law firm philosophy and with what people do you want to practice? It’s not a question whether our philosophy and culture are better or more correct, it’s that it is best for us. That’s one of the reasons we want to hire people right out of law school or judicial clerkship programs, because we do care about our culture. We want the first shot at impressing people with our own culture.

JG: It’s the best way for us. So we decided to leave on a Thursday and we were gone on Monday. We went from zero to 60 in no time at all – like doing a swan dive off a 50-story building. We left without one client. We walked out with 25 lawyers and 25 staff and an obligation to take care of 50 people and their families. And nobody missed a paycheck.

To this day, we have the same bank that helped us do that. The same IT person, the same health insurance advisor and consultant, the same telephone guy. All the things that made a go of it. There are four crucial things and for us at the time we started, those were the four.

LD: So pre-Katrina, how had the firm developed?

JG: In the beginning, my wife, Tracie, was pregnant, and Lee’s daughter, Samantha, was in the middle of Bat Mitzvah preparation. We had other things going on – heavy practices, community obligations and we knew we would have no income, and for a time no clients, nothing.

LS: Virtually every client we represented before we started the firm joined us in the new firm – whether as admiralty, corporate, banking, litigation or real estate clients. After we opened, we attracted a whole host of new clients.

JG: That’s right. We evolved exponentially. We were able to do plaintiff commercial work we couldn’t have done before, and had a lot more flexibility. We were humming.

LS: One of our philosophies is “always build and invest for the future.” A few weeks after we started the firm, we were thinking about our future and how we might grow as a firm. Following our number one philosophy of investing for the future, we contacted Tulane Law School to set up interviews for summer associates because we knew our future might be sitting in our library among our summer associate group.

We went to Tulane in February, and we were nothings. We only interviewed the top 10 people in the class. We made offers to all of them and they virtually all accepted.

We thought, “What have we done? We’re going to have a whole library full of 1L’s.” But our philosophy was to bring them in fresh out of law school so we would have the opportunity to show them our culture.

LD: And since then?

JG: With litigation, we handled major cases, representing New Orleans institutions like Touro Infirmary, Tulane University, Xavier University and others. In the beginning we were asked by Phelps Dodge to handle major litigation in El Paso for them and successfully resolved it. We have had the pleasure of representing Air Liquide America, Rain CII, and Murphy Oil Corporation for more than 20 years. We’ve handled several major commercial matters for New Orleanian Darryl Berger, who owns the Windsor Court Hotel, the Omni Royal Orleans and the Canal Place complex and have tried several cases for Darryl over the years. We are currently representing Texas Brine Company in major litigation in Assumption Parish and regularly try other cases. We represent major financial institutions and other Fortune 500 companies. People have enjoyed our aggressiveness. We were allowed to do some open-field running and the practice exploded.

For our market, we have 45 lawyers, which is the 10th largest firm in New Orleans. From the beginning, all of the clients we were representing at the bigger firm, we were able to serve working with a smaller, tighter group but off of a big-firm platform. And from the transactional side, we were able to rise and handle deals that were multistate, regional and national.

LS: And today, we’re handling some of the biggest matters in our firm’s history, including a multi-party sinkhole case that Jim is working on and where he is the lead trial lawyer for the defense. We would also note that one of our key litigators on that case working with Jim is Amanda Russo Schenck who just had a baby recently, so we’re celebrating that too. It’s part of our family approach to things, which in the long run, we hope, will make everyone here happier, both personally and professionally.

LD: So life is pretty good.

LS: We are so lucky. And we would be remiss if we did not emphasize that without the deep love, support, help, hard work, understanding and care of my wife, Karen, and Jim's wife, Tracie, we would not have been able to start the firm, nor endure the Hurricane Katrina adventure. We are forever grateful to them. They are the rocks of our existence and the foundations of our families.