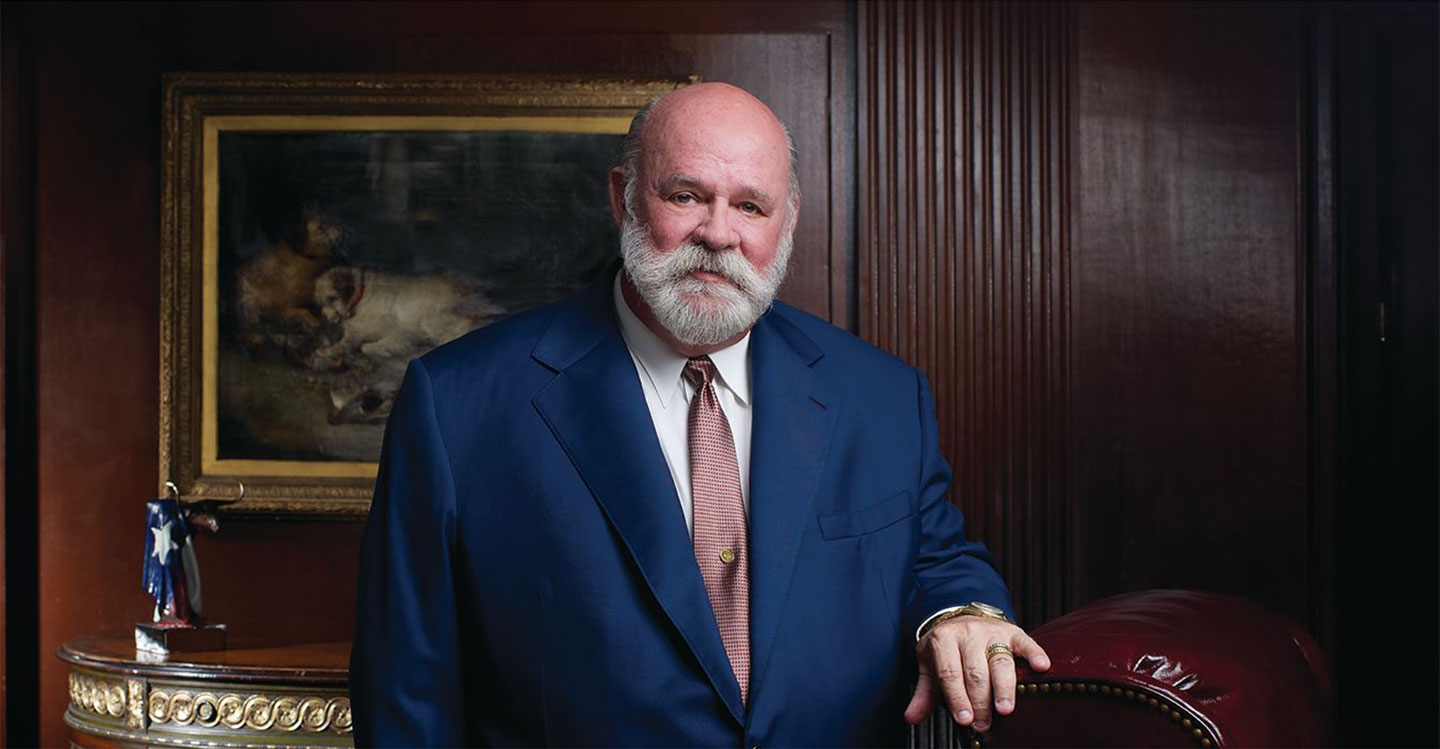

Lawyer Limelight: Frank Branson

By Katrina Dewey | June 16, 2020 | Lawyer Limelights, Plaintiff Consumer Limelights

Humankind grows more wise as the years pass – think of Apostle Paul writing of speaking as a child before putting away childish things or Robert Frost penning, “The afternoon knows what the morning never suspected.” That truism also applies to successful attorneys.

There’s a beauty in discussing the value of experience with Dallas’ top plaintiff lawyer, Frank Branson. At the end of his junior year at Texas Christian University, he was accepted into Southern Methodist University Law School. At the end of his first year in law school at SMU, TCU sent him his degree. He has since won every award there is, while continuing to belt monster verdicts out of the jury box every year.

As a young and ambitious attorney, the Dallas trial lawyer took a more calculated and singularly focused view regarding the value of prospective cases. He was less inclined to take on catastrophic injury or wrongful death cases involving elderly victims because, typically, as plaintiffs they had lower earning capacity which combined with a diminished life expectancy to make it more difficult to win higher damage awards.

After running his own practice for four decades, “I realized that sometimes a candle burns brighter at the end than it does in the beginning,” says Branson, whose victories in personal injury cases range from a $242 million verdict against Toyota over defective car seats that resulted in devastating injuries to two children to a $7 million verdict for a college soccer player whose leg injury in an SUV rollover ended his sports career.

A little over a decade ago, in 2007, Branson persuaded a Texas jury to award nearly $21 million to the 83-year-old widow of a 76-year-old man killed when the couple’s vehicle was struck by an 18-wheeler whose driver tested positive for cocaine afterward and had a history of crack abuse.

“I have enjoyed representing clients in their late 70s and 80s when bad things happen to them,” Branson says. “I believe it becomes a compelling story.”

The key, he learned, was relating that story to a jury, making clear that the value in an individual’s life is more than net worth, that it encompasses less tangible activities such as caring for family members, volunteering in community groups and artistic creations.

“You understand it when you begin to lose loved ones, your mother, your father,” Branson says. “It begins to dawn on you at that time.”

Lawdragon: With the population aging and health issues posing an increasing concern, to be able to tell an older person’s story - which by necessity incorporates their whole life - and negotiate monetary value based on that is a tremendous skill. It’s inspiring that you’ve found a way to get justice for older people.

Frank Branson: You can't always. But when you listen to their case on the front end, and you follow things, it’s easier. With the 18-wheeler case, the impact of the crash pushed Robert Bohne’s car off to the side and it broke his back and several ribs, causing him to have some mild traumatic brain damage. He was laid up at Parkland Hospital for about six months and died at the age of 76.

Kathleen and Robert had a storybook romance. She was British and had married an American GI during World War II; he died in his late 30s of an aneurysm. When she remarried, it was to Robert, a truck driver in his late 30s who had never married. After he retired, he got up every morning, drew her a bath, cooked her breakfast, drove her any place she wanted to go, and built a porch on the back of their house so that she could sit out and have coffee in the morning and watch the birds.

LD: That’s lovely.

FB: As we started digging into the case and ordered his funeral bills, we found out he was a decorated soldier from the Korean War.

LD: She hadn't known?

FB: No, she hadn’t. It was fascinating. She had this beautiful British accent and a real sense of humor. He was her life. And when the accident took his life…

LD: In a sense, it took hers.

FB: Before we got to trial, the defense called in a million-dollar offer, which we didn't respond to. A day or two into trial they raised it, and then asked for a meeting in our office one night and offered her $3 million, which they said was the most they would ever pay. We made a counter-offer, and they said, “Never happening.” Ultimately, the jury gave her $21 million.

LD: And that’s why you do this, right? When you can help people like Kathleen, you show others that if you fight, you can get justice. It’s wonderful to see value put on the lives of the elderly. You see that there’s more to a life than the value of a person’s earning capacity; these are parents, grandparents, they make coffee in the morning for their spouses, volunteer in the community.

FB: Right. It took me a while as a lawyer to understand that. And it took me a while as a person to understand that.

LD: And partly, that’s because economic analysis has become such a focal point in the law. It’s easy to forget that a value should be ascribed to humanity and to what you do with your community and your family, even if it's not that you would have earned $10 million from working over your next 30 years. It’s wonderful that you’ve taken on those kinds of cases amid what was already an inspiring career. What interested you in becoming a lawyer in the first place? Was it your parents?

FB: In a way, though neither of them were lawyers. My dad was a high school coach and my mother was a high school tennis coach, so competition came naturally. My favorite subjects were history, government and speech. My mother also wanted me to be a lawyer, and that had an impact.

LD: Where did she get that idea?

FB: I have no idea.

LD: No lawyers in her family?

FB: No. I assume it had something to do with how well I did in speech courses.

LD: Did you ever think about becoming a teacher like your folks?

FB: No, I really didn't. I was proud of both of them, but coaching would have been what I was interested in. I decided I'd rather do something else. My younger brother became a coach. I knew when I went to college I wanted to be a lawyer.

I didn't know any lawyers and didn’t have any idea, really, what lawyers did. I liked the concept of becoming a lawyer, though, and I have thoroughly enjoyed the profession.

LD: At what point did you develop the notion of being a courtroom lawyer, a plaintiff lawyer?

FB: When I was in college. At the end of my junior year at Texas Christian, Southern Methodist University offered me a scholarship and allowed me to enter law school and get a degree from TCU after my first year of law school. I got a job in my second year as a waiter, and I waited on tables at a steak restaurant for a while.

LD: Here in Dallas?

FB: Yes. Steak & Ale. So if you can wait on a table for six people who have been waiting in the bar for an hour drinking and are hungry, you can do just about anything that involves people. It provided great experience in selecting juries and getting along with people. And after about a year of that, I took a job as an independent insurance adjuster. And in adjusting claims for insurance companies, I became disenchanted with the way insurance companies treated the kind of people I had grown up with. They investigated cases early and slanted the testimony toward the defendant, then tried to starve the plaintiff out by drawing out the case as well as the payments to the plaintiff even after a settlement.

At that time, the insurance companies would pay the plaintiff without a lawyer “X” amount. Eventually, a long time after the accident, they would pay them “X”+5 if they got a lawyer who they knew was going to settle the case. And they'd pay “X”+10 if they got a lawyer who was going to do some work on it, try to settle it after some work, and then refer it to a trial lawyer if it didn't settle. At that time, the late 1960s, in Dallas, there were very few law firms that were truly plaintiffs’ lawyers who could afford to pay for preparing the case and trying it – and had lawyers capable of taking it to trial. The insurers paid those two or three firms whatever it took to get the case settled at the courthouse if they were worried about it. I decided I wanted to be in that group of lawyers.

LD: Good call.

FB: I thought I could change the dynamics. Even with the really good lawyers, the insurers would wait until they were on the courthouse steps to try to settle the case. So I tried to turn the dynamics around in the following ways. First, I went back after law school and got a master's of law in legal medicine at SMU.

And then I tried to move the decision-making point from the courthouse steps back further, using video. So I'd take video statements of everything that I thought was injurious to the defendant, or positive to my client, then invite the defense to my office, serve them a nice dinner and a nice bottle of wine, and show them the video, give them a demand that they could pay within 30 days. And if they didn't pay it, I'd raise the demand. And that worked. I had to try the first half a dozen lawsuits, though. You can't just say that and not do it.

LD: How long did you work as an insurance adjuster?

FB: For about a year and a half.

LD: So you saw that playbook.

FB: Yes. And I felt like Gen. George Patton in the movie “Patton,” where he says to the Desert Fox, General Erwin Rommel, "I read your book, you son of a bitch."

LD: It sounds like you were able to relate to the insureds early on, in part because of your background.

FB: Yes. We were just average folks.

LD: What was your first job as an attorney?

FB: I started out with a two-person firm in Grand Prairie because I knew, by that time, I wanted to be a trial lawyer, and they told me I could try whatever I wanted. A lot of the firms I interviewed with were going to put me in the books for two or three years and let me deal in the Justice of the Peace courts and the county courts. And I wanted to get in the courtroom and learn how it worked.

The first year I was with them, I tried a capital murder case, some other criminal cases and a truck wreck here in Fort Worth. Among others, I also handled a divorce, which showed me enough to know I never wanted to try a divorce case again.

LD: What other lessons did you learn from that assortment of cases?

FB: That the client and the justness of the client's cause made all the difference. And the lawyer is no better than the justness of their client's cause, no matter how hard you work.

I also learned that I really didn't want to be a criminal lawyer and that I enjoyed the civil side. After about a year, a larger plaintiff's firm, Bader Wilson, offered me a job and brought me downtown. John B. Wilson, a workers’ comp lawyer, was my mentor. I carried his bag for a long time, tried a lawsuit or two with him, and then tried other cases.

Like any law firm, manure flows downhill and the new kid on the block is at the bottom of the hill. So I tried a whole lot of lawsuits that in later years I wouldn't have taken. Over the roughly eight years I was with that firm, and became a partner in it, I got hit with cow patties thrown from virtually any direction in a courtroom. It was great. I won some and lost some, but I tried a lot of cases. And the result is that you feel comfortable when you walk into a courtroom.

Probably the most nervous I've ever been was the first case I tried, which was the capital murder case. When I went to the courthouse, I didn't know I was going to try it. I had done the investigation on the case, and an older lawyer, a highly experienced criminal lawyer, was with me and was supposed to try the case. Our client had participated in an armed robbery where the service attendant was stabbed 37 times. Both defendants were young people, and the older lawyer kept saying our client was going to get off because he was testifying against the other suspect. Then, at what I thought was going to be an arraignment hearing, the other suspect pleaded guilty to nine life sentences stacked. The older lawyer came to me and said, “Son, it's time for you to try your first case. I'll sit with you and keep you out of trouble.”

LD: What a way to get your first trial.

FB: His position was that the client had already admitted to going along with the armed robbery. He had confessed to that, and said he stabbed the deceased a couple of times at the insistence of the other defendant. Participating in the armed robbery made it a felony murder, so all we could do is try to keep him from getting the death penalty. I think he put on one character witness, and I put on the rest of the case.

I would go home at night and read black-letter murder law, and it worked out that the jury stayed out a long time and came back with a life sentence, which was a total victory. I've never walked into any courtroom since feeling nearly as anxious as I did every day in that case. It did make it a lot easier to try many of these other lawsuits, though.

LD: It gives you context for what’s at stake. So after those nine years learning to be a trial lawyer, did you start your firm?

FB: I started it in 1978. I took cases that I liked, where I liked the facts and I liked the clients. I thought I could help them. That's what I've been doing since.

LD: Is there much of a difference between the cases you liked then, and now? Or are they still largely the same kinds of cases?

FB: Cases today share some of the characteristics as my earlier cases. Things change. Your breadth of experience changes and the size and complexity of the cases that are referred to you change. Your understanding of what's happening in a courtroom changes. They call it practice for a reason. You really do get better as you do it more.

Instead of just looking in the front end at what happened, what the special damages are, you look at different things as you grow in experience. What is the story, what are the real facts going to show this jury? Is it going to be a compelling story? Are they going to feel like I do about the client when it's over?

LD: What would you say is the most important aspect of being a trial lawyer?

FB: It's real simple: It's hard work. And generally, those who work the hardest win the case. That's not always true, but it's a real high percentage. Credibility matters, too. And generally hard work produces credibility, but you have to be credible with the court and with the jury, and that takes time. It may take five years, it may take 10, it may take 50 to gain the respect of courts and juries. But you need to be credible. And you stay credible with both by telling them the truth.

LD: They know when you're not.

FB: That’s right. If you say, “I'm going to prove this,” and then don't prove it, they know. The one that I see more than you should is the court asking a lawyer, "We've got a break coming up, Mr. Johnson, in five minutes. How much longer do you need?" And Mr. Johnson says, "I can finish, judge." And 15 minutes later, he’s still talking. And then what do you say to the jury? “Not only am I not credible, I'm keeping you here over break.”

LD: And the jurors may need to use the restroom or be hungry. And every time that happens, it's such a clear signal that the lawyer thinks that his or her needs are more important than those of the judge and the jury.

FB: Right, and it's not a good thing. The other thing that I think is critical is watching the witness. A lot of lawyers have a list of questions, and they go over the list and go to the next question without fully taking in what the witness is saying. And when you can get a witness on the witness stand and begin to follow their thought processes, sometimes you get the witness to agree with your position.

LD: Right. But that, too, ties to the hard work. And it's so important to communicate these lessons. There's no shortcut to knowing your witness and knowing how they think, not just how they're going to respond to questions. And to know that you have to engage with them, and to really know where they're coming from.

FB: The other thing I think is important in trial lawsuits is imagination. You have to look for things that jurors are familiar with and link them to the case. In one trial, I got an expert witness retained by the other side to testify that he had made more money in a certain period of time testifying for defendants than it cost to run the National Guard or the fire department of Tucson, Arizona, where we were in trial. They were just some things that when the jury has the comparative size of what was paid to the expert witness, it makes a difference.

LD: Is that one of the techniques that helps when you get to the point of trying to resolve a case? What’s the most important item in your toolbox at that stage?

FB: That the defendant knows you will be ready for trial and have years of successful verdicts under your belt.

LD: Well, you seem to be a master of the telling detail, like talking about the gentleman who was killed in the car crash building his wife a porch so she could drink coffee and watch her birds.

FB: It's the difference in reading an outline of the book and reading the book.