Next 9/11 Judge Will Inherit Clashes Over Witnesses, New Defender and Covid Safety

By John Ryan | October 16, 2020 | Guantanamo Bay, News & Features

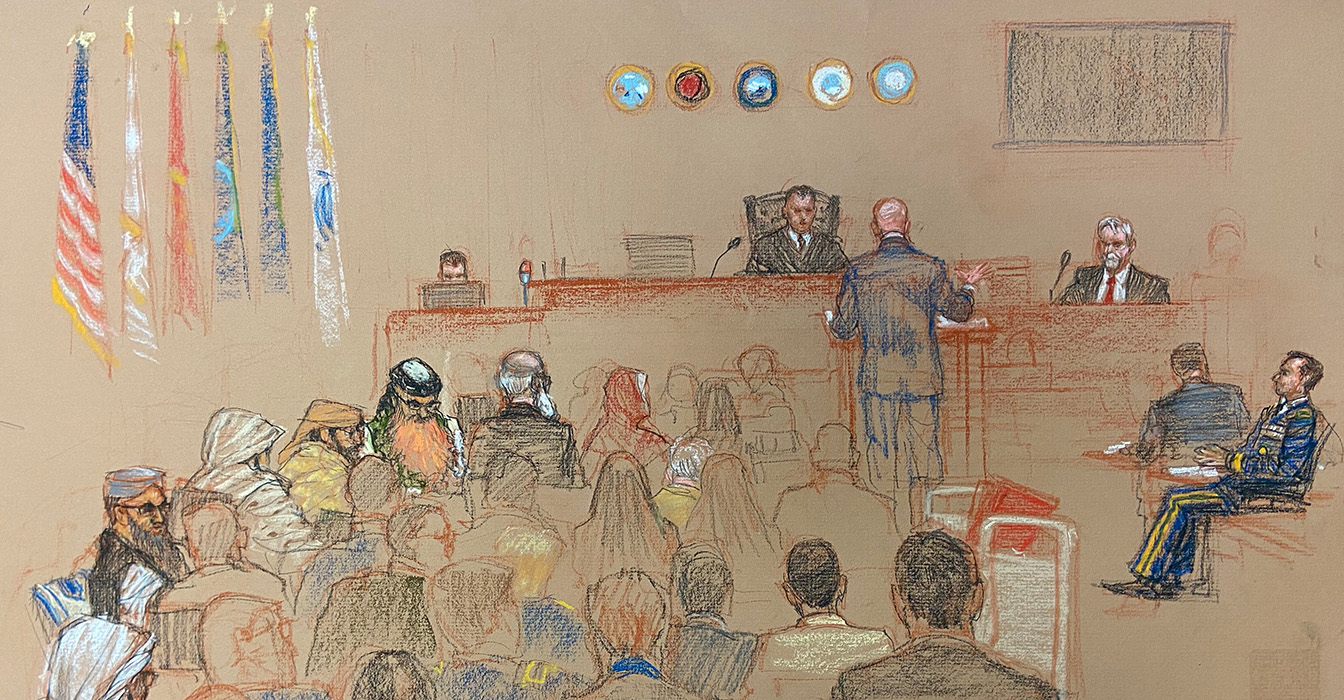

Sketch of Guantanamo courtroom by Janet Hamlin.

The January testimony of Dr. James Mitchell, the contract psychologist who designed the CIA’s controversial “enhanced interrogation” program, was undoubtedly a watershed event in the long-running Sept. 11 military commission on Guantanamo Bay. Much of Mitchell’s nearly two weeks on the stand proved riveting. He testified to his knowledge of the abuse at foreign black sites of the five defendants in court, including alleged 9/11 plot mastermind Khalid Shaikh Mohammad, who Mitchell personally waterboarded more than 100 times. Mitchell teared up on multiple occasions when discussing his work on the disbanded program, which he said was designed to save Americans from another mass terror attack.

“It's a genuine reaction, and anybody who doesn't like it can kiss my ass,” Mitchell said during an emotional exchange on Jan. 28 with David Nevin, one of Mohammad’s lawyers.

For significant stretches, however, Mitchell’s testimony was forgettable. Though all five defense teams view Mitchell as a critical defense witness providing details about what they view as an illegal torture program, his interaction with the defendants, other than Mohammad, appear to have been somewhat limited. Despite their often tense and combative exchanges, Mitchell and the defense lawyers were aligned on one point – that he was just one member of a vast government operation.

On Jan. 30, Cheryl Bormann, the lead lawyer for Walid bin Attash, questioned Mitchell about injuries suffered by her client at the black site referred to only as “Location 4.” Bin Attash’s right leg is amputated from the knee down, which created additional stress on his left leg during 72 hours of standing sleep deprivation for which the detainee was shaven, naked and shackled with his hands kept at chin level in a brightly lit room with loud music playing. (These were “standard” techniques, not the more aggressive “enhanced” techniques that required an additional level of bureaucratic approval.)

Bormann led Mitchell through a series of CIA cables about and photographs taken of bin Attash during the 2003 interrogations. At one point, the cables discuss putting bin Attash in a reclining sleep deprivation position to “avoid unintended injuries,” and later reported the circumference of his left ankle to be 10 inches. Mitchell acknowledged that one photo, which was not displayed to the courtroom gallery, appeared to show a left calf that was “swollen.”

“That would be an understatement,” Bormann commented.

But in that late January session, Bormann could only get so far with Mitchell, who wasn’t bin Attash’s interrogator. That CIA interrogator – identified in court only by the code “NZ7” – is not yet a witness in the case, and may never be.

Mitchell did not even clearly recollect seeing bin Attash at Location 4.

“You'd have to talk to somebody who was there, not me,” Mitchell said.

“Yeah,” Bormann replied. “We’ve tried.”

Whether Bormann and the other teams succeed in getting NZ7 and other CIA personnel on the stand – and how that might be done in a way to protect the witnesses’ covert status – is one of many complex issues awaiting the next judge on the Sept. 11 case. On Thursday, Air Force Lt. Col. Matthew McCall was assigned to the case as its sixth judge in the past eight years. By Friday evening, questions surfaced over whether he had spent the requisite two years on a military bench and prosecutors filed a notice indicating they would seek his recusal if he did not step away from the case.

Whoever the next judge is will inherit the leviathan amidst a cascading sequence of delays following Mitchell’s testimony the last two weeks of January. In February, one of the lead defense lawyers requested to depart the case for health reasons, gutting plans for additional witness testimony in that session – which proved the last to be held. The following month, Air Force Col. Shane Cohen, who had presided over the case since June 2019, announced his retirement from active duty on March 17, citing family reasons.

The chief judge of the commissions system, Army Col. Douglas Watkins, declined to hold hearings during his stewardship of the case as a placeholder judge. Watkins concluded at multiple intervals this spring and summer that the base’s Covid-19 safety restrictions, which require two-week quarantining on base for all visitors, made holding hearings “impracticable,” despite the prosecution’s contentions otherwise.

On Sept. 17, Watkins detailed a new judge, Marine Col. Stephen Keane, to the 9/11 case. Keane cancelled the remainder of the hearings set for 2020 so he could familiarize himself with the proceedings. Then, just two weeks later, he recused himself over potential conflicts of interest that he said could create an appearance of bias.

The chances of of any new judge presiding over the start of a trial before the 20th anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks next year have all but vanished. The prosecution team is seeking the death penalty against the five defendants, which in addition to Mohammad and bin Attash include Ramzi bin al Shibh, Ammar al Baluchi, and Mustafa al Hawsawi.

The next judge is expected to first wrestle with the government’s plan to restart hearings with Covid-19-related protocols, to which the defense teams have filed numerous objections. Once hearings resume, defense teams will have the opportunity to voir dire a new judge on matters relating to background and affiliations and could potentially seek the judge's recusal. Prosecutors oppose McCall because he has been a judge for less than two years, a threshold required by commission regulations.

If he remains on the case, McCall will be in the difficult position of attempting to hold hearings while catching up on the biggest criminal case in U.S. history, which includes almost 35,000 pages of trial transcripts. The next judge also will assume control of the case in the middle of its most pivotal phase to date – a culmination of exceedingly contentious and complex litigation over the Bush-era CIA enhanced interrogation program that has already spanned several years in the Guantanamo courtroom.

Defense teams have called witnesses including Mitchell and his partner in the CIA program, fellow psychologist Bruce Jessen, to support their claims that confessions their clients later made to FBI agents on Guantanamo Bay in 2007 should be suppressed. Lawyers contend that the prior torture and isolation of their clients at the CIA black sites render any subsequent statements involuntary and therefore inadmissible. Prosecutors argue that the 2007 statements – given to FBI agents roughly four months after the detainees arrived at Guantanamo from the black sites – were voluntary because the detainees were given the option of not participating and were allowed to end the interviews at any time. The government’s trial team has said in court that the Guantanamo statements are among the most critical evidence in the case, setting up a potential appeal if the defense teams succeed in their suppression motions.

Prior to issuing a ruling, however, a new judge will have to decide the scope and duration of the suppression hearings. The prosecution and the five defense teams are miles apart in their views on the number of witnesses required to hold fair suppression hearings: The government wants to limit the number to less than 20, while defense teams have argued that several dozen to more than 100 witnesses may be needed. In the military commissions system, defense teams must make witness requests to the prosecution but can ask a judge to compel a witness if the government does not agree to a witness' relevance or necessity.

One tranche of government-approved witnesses – the FBI agents who took the defendants’ statements at Guantanamo in January 2007 – is of great importance to both sides. Prosecutors believe these witnesses can attest to the voluntary participation by the defendants during the interviews, as well as their rational mindset and duress-free demeanor. Defense teams, in turn, have and will continue to probe the extent to which these same FBI agents participated in abusive black site negotiations by sending in questions to the CIA locations during the sessions – as well as the extent to which the agents reviewed information from the black sites before interrogating the defendants on Guantanamo Bay. Defense lawyers believe the level of coordination between the CIA and the FBI undercuts the government’s position that the January 2007 sessions were "clean" or sufficiently separated from the black site interrogations, which the government acknowledges were coercive.

The government wants to circumscribe the CIA witnesses to the two contract psychologists, Mitchell and Jessen, while the defense teams want to call many covert agents including NZ7 – known only to the teams by their code identifications – who either participated in or witnessed the treatment of their clients at the black sites. Defense teams also want to call officials and lawyers from the Bush administration who participated in the decision-making related to the program, formally known as the CIA's Rendition, Detention and Interrogation, or RDI, program.

James Connell, the lead lawyer for al Baluchi, who is Mohammad’s nephew, said in a recent interview that his team – through its own interest in streamlining the litigation and avoiding duplication of information already learned in court – was able to cut its initial list of 101 witnesses roughly in half. He has proposed using a mix of written interrogatories, depositions, and live witnesses in court. Connell said that he wants eight covert CIA witnesses for live testimony, an additional eight by deposition, and one by interrogatory.

“There has been no discussion of how the [covert] witnesses might testify,” Connell added. He said the government opposes his proposal.

Connell’s team was the first to move forward with its motion to suppress, though the other four teams have questioned witnesses, including Mitchell, who have overlapping relevance. Connell has filed a motion to compel his additional witnesses but has acquiesced to holding off arguing that motion until he and the prosecution team get through the witnesses approved by the government.

Mohammad’s team filed a motion to compel 134 witnesses to support its motion to suppress, according to a response filed by the government in late January. Lawyers for Mohammad did not respond to inquiries on whether that number has shifted during recent months.

The government contends that the CIA witnesses should be limited to Mitchell and Jessen because what happened at the black sites “is simply not a matter in reasonable dispute,” according to its response to the Mohammad motion. Prosecutors do not use the word “torture” in court or in pleadings – which they say is a legal conclusion best left for a judge – but they are not challenging the often unsettling and occasionally gruesome details of what was done to the defendants at the black sites.

Prosecutors have provided each team with a “Proposed Stipulation of Fact” related to the treatment of the defendants in the CIA program, and have said in court numerous times that they will sign off on any description of past treatment that is “tethered to reality.” Prosecutors argue that the agreed upon witnesses and the stipulations “will provide a more-than-adequate record of what happened” at the black sites, according to their filing in response to Mohammad’s motion for additional witnesses.

Walter Ruiz, the lead lawyer for al Hawsawi, said in a recent interview that the defense teams have an ethical duty to investigate the case and develop their own set of facts through “a defense lens.”

“We can’t take at face value information the prosecution is willing to provide,” Ruiz said. “There may be layers and layers beyond what is showing up in a stipulation. In a capital case, you can’t rely on a one-sided narrative to defend your client. That would be avoiding your responsibility.”

In fact, Ruiz said, his team’s interviews with covert witnesses have uncovered information inconsistent with that provided by the government and have led to his team’s interest in additional discovery and witnesses. At this point, Ruiz said, he was not sure how many witnesses he would want to call for his suppression hearing beyond those approved by the government.

The litigation over the witnesses the defense is allowed to question highlights conflicting interpretations of the fact pattern surrounding the January 2007 interviews by the FBI at Guantanamo. The prosecution team focuses on the four months that passed from when the defendants left the black sites, alongside reassurances given to them that they would not be returned to CIA custody, to argue that the statements were "attenuated" from the prior coercion.

Lawyers for Mohammad, however, argue in one of their suppression pleadings that it “defies common sense” to assume that their client would somehow be reassured by his new situation.

“Mr. Mohammad was still detained by the United States, still being held without access to family or lawyers, and still under the government’s total control,” the motion states.

The pleading adds that Mohammad was often hooded at the black sites, and his interrogators were often masked, so “he would have no way of knowing or confirming whether the 2007 interrogators” had earlier interrogated or tortured him at the black sites.

Lawyers for bin al Shibh argue in one of their filings that “a large number of witnesses” is needed to rebut the government’s contention that a four-month break creates a level of attenuation needed to support voluntariness.

“Mr. bin al Shibh was not punched by a police officer while resisting arrest an hour before his interrogation,” the pleading states. “He was held for years in a secret, multi-million dollar, global program that was approved by the highest levels of the United States government and that tortured him under the guise of pseudo-scientific theories.”

Producing Mitchell and Jessen instead of the CIA personnel who actually interrogated their client “is like producing the person who came up with the idea of hitting suspects with rubber hoses” instead of the individuals who implemented the techniques, the pleading states. (That filing does not list a specific number of witnesses; lawyers for bin al Shibh declined to comment.)

A lingering dispute over the defense teams’ ability to merely make contact with potential covert witnesses makes the litigation over suppression even more confusing – and surely even more challenging for McCall or any new judge to wade into. Three years ago, the government blocked defense teams from independently contacting any CIA personnel with knowledge of the interrogation program. The prosecution instead provided each defense team with an index of individuals listed only by the code identifications who had substantial contact with their clients at the black sites. Defense teams have had to go through the government to request interviews with these individuals, who are not required to participate.

The first judge on the case, Army Col. James Pohl, concluded that the investigative restrictions unfairly hindered the defense teams’ ability to litigate their motions to suppress the 2007 FBI statements. In August 2018, he prohibited the government from using the 2007 statements “for any purpose.” That ruling, which came just a month before Pohl retired and left the case, effectively suppressed the FBI statements without holding suppression hearings.

His successor, Marine Col. Keith Parrella, reversed Pohl’s ruling as “premature” and decided that the defense teams should move forward with their motions to suppress. Parrella said in his April 2019 ruling that he might ultimately agree with Pohl that the restrictions were too severe, but he first wanted the defense teams to “use all tools at their disposal” in arguing for suppression.

The third judge on the case, Air Force Col. Shane Cohen, adopted Parrella’s approach when he took the reins in June 2019; he moved forward with the first witnesses for the suppression hearings last fall. In rejecting defense motions to reconsider Parrella’s ruling, Cohen reasoned that the defense teams could develop a record through the hearings and later file motions asking for some type of remedy or relief based on any negative effects of the investigative restrictions.

Inheriting this regime, the next judge will be tasked with presiding over the suppression hearings while also assessing the fairness of the proceedings, into which he or she will be arriving midstream. This subset of the litigation may lead to a separate group of witnesses. Mohammad’s team has filed a motion to compel eight additional witnesses, including experts on the practice of capital defense, to testify on matters relating to the impact of the investigative restrictions. The government opposes that motion.

Even the more streamlined suppression hearing sought by the government is likely to stretch over multiple months once the case resumes; the parties have not yet finished with the former CIA contract psychologists. Mitchell testified for nine days in open session but still must face defense examinations in a closed session in which classified information will be elicited. Only Connell’s team for al Baluchi had begun its examination of Jessen during the January hearing.

However, even before tackling suppression or ruling on witnesses and defense requests for additional discovery – let alone any of the dozens of other motions unrelated to suppression that are pending – the next judge will have to resolve the status of the defense team for Ramzi bin al Shibh. In February, bin al Shibh’s lead lawyer, James Harrington, brought the suppression hearings to a halt by requesting to leave the case for health reasons. Cohen granted the request, though he required Harrington to stay on the team to serve as a resource for his replacement. Each defendant facing a possible death sentence in the military commissions is entitled to a “learned counsel” with experience in capital defenses.

Harrington’s replacement, David Bruck, said in a July transition plan filed with the court that he would need 30 months to develop a relationship with bin al Shibh, familiarize himself with the pretrial litigation and team strategy, and prepare for trial.

Bruck, 71, has represented several high-profile capital defendants, including Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and Dylann Roof, who killed nine people in a South Carolina church. Bruck noted in his filing that the 9/11 case involves about 500 substantive motions and 8,500 filings. He added that, to his knowledge, the 9/11 case also is “the first in the modern era of American capital punishment” involving more than four defendants facing a death sentence.

“The obvious problem with comparing this case to other similar cases is that there aren’t any,” Bruck wrote in his plan.

Bruck also said in his filing that he assumed the 30-month preparation period would not begin until face-to-face meetings with bin al Shibh are “practicable.”

Significant preparation time for Bruck, if allowed by a new judge, would raise the prospect of that judge deciding to sever bin al Shibh from the case so that the proceedings could move ahead against the other four co-conspirators.

The prosecution team was highly critical of the transition plan in its reply and urged the judge – at the time Watkins, the chief judge of the system then serving as placeholder – not to entertain either a 30-month delay or severance. Prosecutors contend that Harrington should only be released if Bruck “abandons his current posture and takes on an actual detailed role in the case.” Prosecutors said that Harrington could participate remotely for court hearings to assist Bruck and the other civilian and military lawyers who represent bin al Shibh. (Watkins did not rule on the dispute, leaving it for McCall.)

The Chief Defense Counsel overseeing the defense operations, Marine Brig. Gen. John Baker, described Buck as imminently qualified and a lawyer of integrity.

“If David Bruck says he needs 30 months, he needs 30 months,” Baker said in a recent interview.

Baker said that prosecuting bin al Shibh “before his capital defender is ready” would be a judicial error eventually resulting in the case being tried a second time.

“And I don’t think anybody wants to try these cases a second time,” Baker said.

In late August, the prosecution team filed a proposed “60-Day Plan” with a series of protocols involving quarantining and testing intended to allow the safe resumption of proceedings in the case, to which the defense teams have objected. Before recusing himself after just a few weeks on the case, Keane said he would use the government plan and defense-team input to develop “a realistic schedule for hearings in 2021.”

That task will be one of a mountain greeting McCall or whoever takes the case. However, even the most detailed and comprehensive safety plans may not reach a level of satisfaction among members of defense teams for age or other health-related concerns. Given the objections filed to the government’s plan, a new judge may encounter a situation in which he sets a hearing schedule but critical participants decline to show up.

Mitchell's highly anticipated testimony in January – and the progress in pretrial litigation it reflected – has become a distant memory. In February, Judge Cohen may have tempted the Guantanamo Gods by touting the progress in his oral ruling releasing Harrington from his lead role for bin al Shibh.

On Feb. 19, Cohen said that since taking the case in June 2019, he had successfully worked with the parties “to overlay structure on a process that for over seven years had none.”

Though his plan for an early 2021 trial date might shift, Cohen said, “there is no doubt that this case is on the best footing and has the best opportunity to get to trial that it has had in the past eight years.”

About the author: John Ryan (john@lawdragon.com) is a co-founder and the Editor-in-Chief of Lawdragon Inc., where he oversees all web and magazine content and provides regular coverage of the military commissions at Guantanamo Bay. When he’s not at GTMO, John is based in Brooklyn. He has covered complex legal issues for 20 years and has won multiple awards for his journalism, including a New York Press Club Award in Journalism for his coverage of the Sept. 11 case. View our staff page.