The Great and Grand Adventures of Attorney Geoffrey L. Harrison

By Katrina Dewey | December 29, 2020 | Lawyer Limelights, News & Features, Susman Features

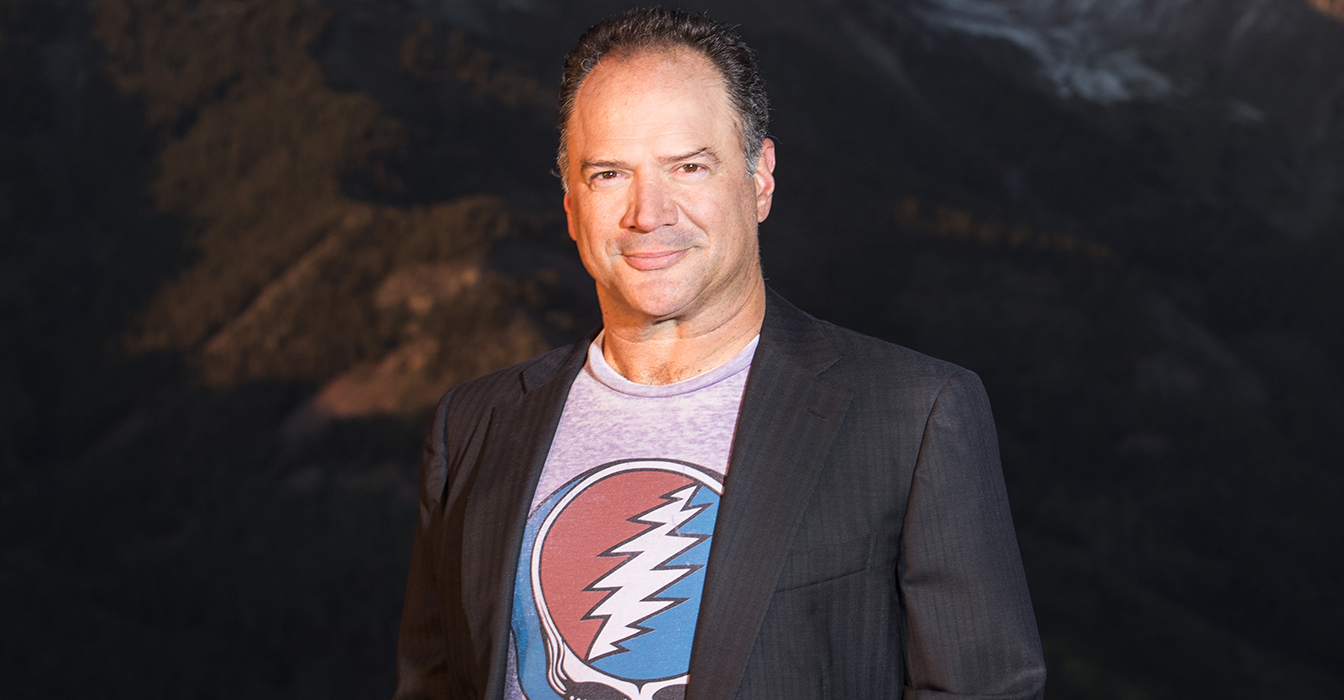

Photo by Kaycee Joubert.

If clothes make the man, Steve Susman was bewildered.

Before him stood the prodigy. The top first-year law student at the University of Chicago law school in the fall of 1989.

Yellow Sigma Alpha Mu fraternity sweatpants – right leg properly down at the ankle, the left one oddly pulled up to the knee. The white T-shirt was normal enough, but why was he wearing his red Champion Penn sweatshirt inside out?

And those shoes … Reeboks were one thing, but with Velcro closures?

A fraternity baseball hat on backwards. Because of course.

Ice ice baby.

The great and grand adventures of Geoffrey L. Harrison did not, of course, begin the day he met Steve Susman. And, to be complete, here is how the rest of that showdown went:

Steve Susman: “Hey, how’d you like to work at the best law firm in Texas?”

Vanilla Ice’s poorly dressed cousin: “I’ll give you half my summer.”

The kid don’t play.

The life and times of Harrison have been set to song by his partners in an homage of “Hamilton”; recounted in countless bars and seaports worldwide; and captured in his own private compendium – a Valentine to Susman Godfrey, his home of 27 years and counting. For this written account shared with Lawdragon, think “The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe” as written by Jack Kerouac and hosted by Anthony Bourdain:

Wearing cowboy boots, a white shirt, dark blue suit, blind-justice suspenders, and a tie, I stepped off the elevator on the 51st floor at 8.30am sharp and threw in my lot with the folks here at Susman Godfrey, LLP. It was Monday, September 27, 1993. … Receptionist Marie Trahan greeted me without a flicker of recognition – a fine reward for all my hard work as a summer associate at SG in 1990 and 1991. HR Director Madelyn Foster asked me to sign a letter acknowledging that my employment was “at will” such that the firm could terminate my employment any time, without notice, and without cause.

“It has been one hell of a fantastic ride, and the ride is yet young,” says Harrison in an extended interview this year. He has won countless victories on plaintiff and defense for insurers, oil and gas companies and global contractors accused of everything from pollution to oil spills to defectively manufacturing military gear to good old-fashioned contract breaches. He protected the Houston Equal Rights Ordinance and its LGBTQ safeguards. And while his practice has included disputes in Alaska, California, Delaware, Illinois, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas, Washington, Brazil, England, France, Greece, Morocco, Puerto Rico, Slovenia, Spain and Venezuela, it started off in downtown Houston.

That’s where, over a Treebeards’ fried chicken lunch, Lee Godfrey told Harrison he would be examining the next two witnesses in a hard-fought accounting malpractice battle against Deloitte.

That afternoon.

Just one month after Harrison started practicing law, he and the Susman Godfrey team won a verdict lawyers spend their whole careers hoping for: $77,685,000 against Deloitte.

That evening, Harrison learned the fine art of celebration Susman Godfrey style – in the wine room at Tony’s in Houston where they drank and sang show tunes until the accordionist packed up and the cows came home.

“One thing that I learned early from Lee Godfrey and Steve Susman and others was the importance of having not just fun, but a great time when you practice law, and the way you practice law, and the way you celebrate successes,” says Harrison. “It has stuck with me. I live it. I teach it. It’s part of what fuels my love for the firm.”

In truth, he had already picked up on the work hard-play hard vibe as a summer associate:

[Max] Tribble and Jeff Chambers had taken me out for a recruiting dinner at La Colombe d’Or. We spent 7½ hours, blew through the 1939 Armagnac, and made a respectable showing with the 1944. The maitre d’ tossed Tribble the keys at 2.30am and said lock up when you’re done. I never saw the check but a somewhat flushed Tribble and Chambers took me aside the next day and said “If you don’t accept our offer, we’re finished at the firm.”

Limits were imposed, but only on how much was spent. Not on investment in the ties that bind, which Susman Godfrey does better than perhaps any other firm. “That story, it really sticks with you, and frames relationships. Max and I have been extremely close for 30 years. I think we would’ve been close even if we hadn’t finished off the ‘39 and gotten into the ‘44 Armagnac. But who knows? Maybe not. Maybe that’s what it all comes down to.”

Harrison spent the first years of his life in Wilmington, Del., where his dad worked as an engineer for DuPont. His mom would pester his father: “‘Why don’t you go to law school? Why don’t you go to law school?’ Finally, my dad said, ‘Why don’t you go to law school?’”

She enrolled at Widener and transferred to the University of Houston when the family moved south during Harrison’s 5th grade year. His dad worked full-time as an engineer in the oil and gas industry by day and attended law school at night, becoming an intellectual property lawyer; Harrison’s mom practices family law.

A relatively good and responsible kid, Harrison sought an edge in basketball (lasted two weeks), and sartorial splendor (customizing the obligatory Polo shirt). At Houston’s Johnston Junior High and Bellaire High School, he found a perch in student government and competitive debate and oratory. As a senior, he won the Texas state championship for extemporaneous speaking.

“I always thought the trophy could have been bigger,” says Harrison. He attended the University of Pennsylvania for undergrad, continuing his passion for the Wars of the Words.

Eighteen countries sent their best debaters to the World Universities Debate Championship – where he competed in parliamentary style debate. He traveled to three global speakfests: at University College in Dublin, Ireland; University of Sydney in Australia; and at Princeton University. Trivia: In his senior year, he and debate partner Brad Handler debated Ted Cruz and his Princeton debate partner twice and won both times. “In fairness,” says Harrison, “we were seniors when Ted was a freshman and by the time Ted was a senior he and his partner won ‘team of the year’ and Ted won ‘speaker of the year’ honors.”

Double trivia: His senior year, Harrison and Handler took fourth in the world. “Which was great, although I think we got robbed,” he says.

On to the South Side of Chicago, accompanied by his then-rare laptop computer. Harrison excelled, graduating at the top of his class with law review and moot court honors. He garnered clerkships at Susman Godfrey and Fulbright; then New York and Chicago. After his 1L stint at Susman, he went down the block to Fulbright, where he luxuriated for six weeks in the corner office recently vacated by legendary David Beck, who had left to form his own firm.

Rarely one to say “Enough!” he clerked again after graduating, spending his third summer at Irell & Manella in L.A. instead of studying for the bar. He took two anyway: New York and Texas, all in the course of four days. He flew to Albany on Monday, met a friend for dinner at Sizzler, studied his notecards, took the New York bar Tuesday, flew to Austin, studied with UT friends, took the multistate Wednesday and the Texas bar Thursday and Friday. That night, July 31, was his birthday and some damage was done at The Oasis on Lake Travis.

Next to Jacksonville, Fla., where he clerked for Chief Judge Gerald Bard Tjoflat of the 11th Circuit starting late August 1992. Within a month, Steve Susman rang.

Steve Susman: “Harrison, we want you to come work at the firm. This is a job offer.”

Geoffrey Harrison: “Steve, that’s great. Can I think about it for a couple of days and get back to you?”

Steve Susman: “What the fuck are you going to think about?”

Fair point. Harrison accepted. “I was attracted to the way that Susman Godfrey was plainly a great firm with wicked smart lawyers but was still hovering about on the fringes of respectability,” Harrison says. “Where there’s a lot of smoke and mirrors out there, we are pure fire.”

His substantial practice may best be defined set to the tune of B.J. Thomas’ “Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song”:

Hey, won’t ya play another somebody done somebody wrong song

And make me feel at home while I miss my baby, while I miss my baby…

“I represent the wronged and I represent the falsely accused, the supposed wrongdoers,” says Harrison. “I have had the good fortune that it has worked out that my clients always seem to find themselves on the right side of the dispute.”

Take, for instance, Harrison’s journey to Oroville, Calif., to defend Aetna’s denial of coverage for environmental damage caused by Koppers, a creosote manufacturer. Harrison’s job was to cross-examine a plant manager who testified that while there was a bit of creosote on the ground, it was not much to be concerned about.

Harrison: “So you saw this creosote on the ground and you didn’t do anything about it?”

Witness: “No, not really.”

Harrison: “Why not?”

Witness: “I didn’t think it was that bad.”

Harrison: “You didn’t think it was that bad for your health?”

Witness: “Not particularly.”

Harrison: “Well, let me ask you this. Did you ever drink any creosote?”

Witness: “Of course not.”

Harrison: “Why not?”

Witness: “It wasn’t part of my diet.”

Harrison: “Not part of your diet? I’m sorry. Are you saying the only reason you never drank creosote was because it wasn’t part of your diet?

Witness: “Well, it wasn’t.”

That was one of 50 depositions Harrison took in his second year of practice. The following year, he bested Sullivan & Cromwell in a $150M Atlantic Tele-Network securities trial in St. Croix federal court. Hurricane Marilyn’s 115 mph winds bumped the original trial date, so with only mild hesitation from a client who was also 50 percent owner, Harrison led the three-day bench trial against a Sullivan & Cromwell team.

From Harrison’s written account:

Trial featured openings, closings, and eight witnesses. Our local counsel (who raised goats on the side) handled two witnesses and I handled everything else. The client rented us and our witnesses a grand house perched on an outcropping into the Caribbean, and I made aggressive use of the house’s in-ground trampoline as I fired myself up each day for my first unequivocally lead role at trial. …

Two weeks later, the St. Croix federal court ruled for us on all issues …. Two years later, the International Commercial Litigation magazine ranked Big Daddy Susman the No. 1 litigator in the world, ranked Godfrey No. 6, and ranked No. 3 the Sullivan & Cromwell lead partner I had crushed in St. Croix.

The defense of Enron affiliates took center stage as Harrison moved into his third year, spending months in Midland, Texas, defending multiple oil and gas producers every day. Alongside Susman and Neal Manne, Harrison successfully defended three of Enron’s pipeline affiliates that October. In December, they found themselves in an arbitration defending the same affiliates against nearly the same claims and certainly the same plaintiff lawyers – and again won:

That arbitration took place on Thursday, Friday and Saturday. During a lunch break on Saturday, Susman and Manne went to the partners meeting and returned 1 ½ hours later. Neither said a word to me or cast so much as a glance in my direction. We went back on the record and Susman rose and announced that I had just been elected to the partnership a year early. I was blown away and had to leave the hearing room. When I returned, Manne leaned over and whispered words in my ear that in many ways still capture the ethos of SG: “The good news is we made you a partner. The bad news is we f*cked you on your bonus.” Several of us went out that night, and Rivera gave me a bottle of DP and I drank it straight from the bottle.

Has any lawyer ever had such fun? Over so many miles and so many trials, the preening potential of “Yo, VIP, let’s kick it” became the loud, thumping “U Can’t Touch This.” The early success of Harrison, Tribble, Vineet Bhatia, Robert Rivera and now federal judge Charles Eskridge launched an annual bacchanal commenced the first time the young guns brought in real money. There was dancing throughout the restaurant and a riot over newfound wealth. Sidenote: Remember when making a million bucks was a cause for celebration rather than navel gazing over who made $1.2M? Not that the Susman Godfrey gang has rode in that rodeo class for many years now …

The joy in representing clients and winning – and making money – is matched by the friendship and the role he often plays as mentor to younger attorneys. Throughout Covid, as he and his closest colleagues have hung out in their Telluride aeries, Zooming while hiking through the mountains, he’s taken intense pride in helping to create the next generation of great Susman Godfrey trial lawyers.

Harrison’s story is particularly well told because he’s memorialized it – and because he has a crazy memory for what he ate, what hotel room he was in and what half marathon he ran in the midst of a trial. But among Susman Godfrey’s partners, there is a singular revelry in the joy of the law and its spoils – however they are celebrated. That continued unabated from second homes far and wide throughout this annus horribilis.

Wine Zooms were held, mass litigations were marshalled, bike rides were taken, a spirit captured by Harrison’s favorite band:

Reach out your hand if your cup be empty

If your cup is full may it be again

Let it be known there is a fountain

That was not made by the hands of men.

Steve Susman died on July 14. He fell on a bike ride in Houston with others from the firm. During his recovery, he was claimed by Covid.

When Harrison called from Telluride in late September, I was momentarily transported. Harrison’s relationship with Susman sprung from deep waters – and they continue to audibly echo in Harrison’s voice and vocal mannerisms.

“I loved Big Daddy and I miss him. Steve and I tried and won cases together. We jogged, traveled, dined, drank, cursed, and howled in laughter together. The Susman Godfrey family – partners, associates, staff, everyone, and most definitely me, included – owe our professional and personal happiness to Steve and to Lee Godfrey, too,” Harrison says. He and his wife Lauren and daughters Layla and Lilly, as well as Tribble, Bhatia and their families were quarantined in Telluride. They gazed at the mountains and more than one toast was made.

In true Big Daddy style, Harrison presented a contingency case at the next Wednesday meeting. “I was all red eyed and whatnot and I got through it and the firm approved the case.”

At the most recent “(Not So) Young Partners” celebration, Harrison had pre-ordered a mastodon-size tomahawk steak for Susman, whose appetite for life and its spoils were captured that night. The firm founder left such a profound imprint on those around him – the master of the F-bomb; the creator of plaintiff commercial contingency litigation; the partier in chief. The prankster who routinely made bets at firm retreats – $10,000 to swim in a shark tank, propose to a loved one, lasso a man-eating iguana. And who equally routinely did not pay, often following a legal objection over the currency in question, the definition of lizard or the like.

Talking to Harrison and his partners, those debts are paid – they always were. Forward.

There is a road, no simple highway

Between the dawn and the dark of night

And if you go no one may follow

That path is for your steps alone

Ripple in still water

When there is no pebble tossed

Nor wind to blow

La da da da

About the author: Katrina Dewey (katrina@lawdragon.com) is the founder and CEO of Lawdragon, which she and her partners created as the new media company for the world’s lawyers. She has written about lawyers and legal affairs for 30 years, and is a noted legal editor, creator of numerous lawyer recognition guides and expert on lawyer branding. She is based in Venice, Calif., and New York. She is also the founder of Lawdragon Campus, which covers law students and law schools. View our staff page.