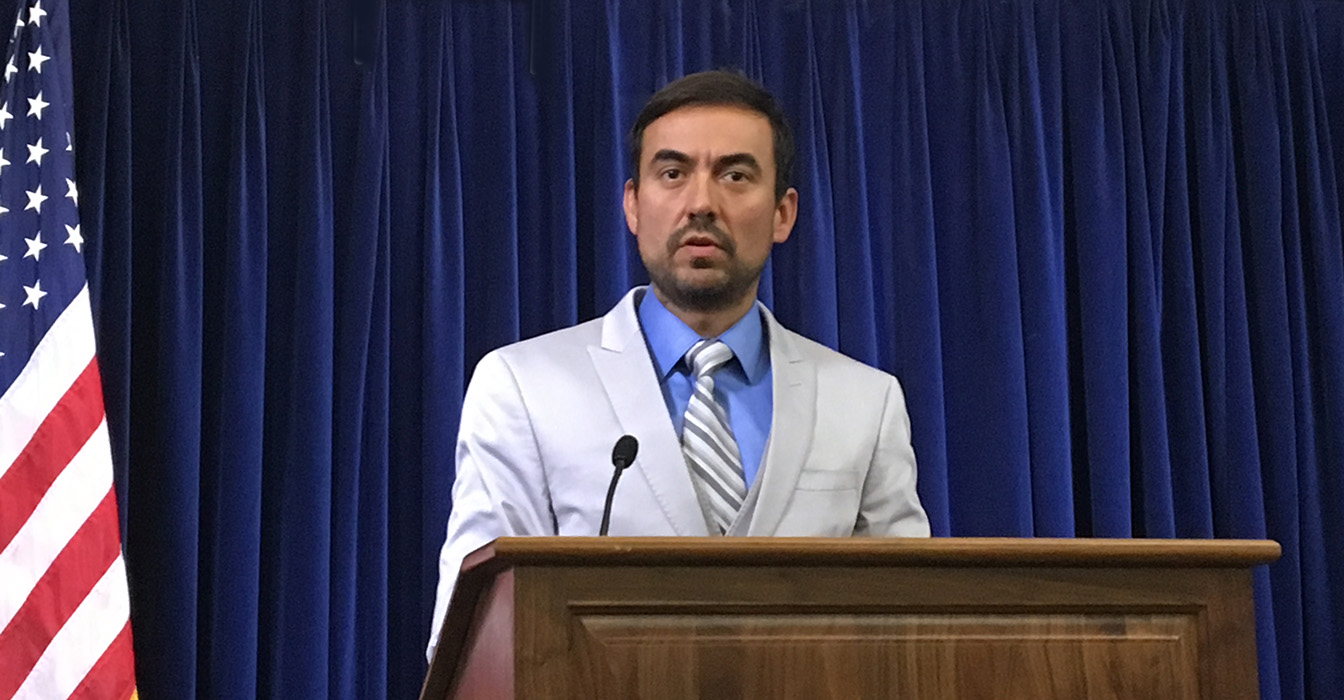

You wouldn’t guess by watching the Sept.11 military case at Guantanamo Bay that Walter Ruiz, as a law student at the University of Georgia, imagined himself a future prosecutor, or that he was disappointed after being assigned to a defense position as a young lawyer in the U.S. Navy. It was a serendipitous turn, however, one of many that has led the Colombia-born Ruiz to conclude that life has guided him more than he’s “driven life.” The role not only confirmed to Ruiz that he was a trial lawyer at heart, it also taught him that he liked fighting for the underdog.

“I learned in those first four years of military work that not everything is black and white,” Ruiz says. “What I tell people is that in this line of work I have to look for the good in people in some of the worst circumstances, to try to extract the positive.”

After those first four years, Ruiz left the Navy to avoid a supervisory position that would have taken him out of the courtroom. He instead served stints as a state public defender in Orlando and a federal public defender in Tampa before eventually returning to active duty for the military commissions. A triathlete who completed the Wisconsin Ironman in September, Ruiz is drawing upon all of his experience and physical stamina as lead defense attorney for Mustafa al Hawsawi, one of five men facing the death penalty for their alleged roles in the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. The case has been mired in pretrial litigation since the May 2012 arraignment.

Al Hawsawi is accused of helping the hijackers by sending them money and supplies. Like the other defendants, he spent multiple years at CIA black sites before he was transferred to Guantanamo Bay in 2006. The defense team portrays al Hawsawi as a relatively minor figure in the alleged 9/11 conspiracy and contend that the government should prosecute him separately to provide a fair trial. The judge, Army Col. James Pohl, rejected the team’s motion to sever al Hawsawi earlier this year.

Ruiz also portrays al Hawsawi as a torture victim who endured “sodomy under the guise of medical treatment” by his CIA captors, and whose continued suffering is hampering his ability to fully participate in the pretrial proceedings. The 48-year-old Saudi underwent surgery late last year to alleviate persistent pain in and bleeding from his rectal area. The government characterized the surgery as a hemorrhoidectomy; Ruiz says that “seeing is believing” and that a pre-operative photo would convince anyone of the severity of the condition.

As the pretrial phase has grinded on, tensions have risen between Ruiz and the military judge, largely over the defense team’s intermittent requests to either have proceedings postponed or special accommodations made for their client’s medical condition. Judge Pohl requires defendants to show up on the first day of each court session but allows them to subsequently stay back at the Camp 7 detention facility if their waiver to attend is voluntary – a potentially tricky standard to apply to al Hawsawi given his health. He often decides not to attend, far more regularly than his co-defendants.

One morning during the late August session, al Hawsawi signed the required waiver form but sent along a letter to his team that called into question the voluntariness of his non-attendance. Pohl grew annoyed with Ruiz and ordered the guard force to bring al Hawsawi to the Camp Justice courtroom. Ruiz pointed out that he, too, was caught off guard by the letter.

“What I'm struggling with is the fact that you seem to be irritated at defense counsel in this instance,” Ruiz told the judge.

In a December 2016 hearing, Pohl cut short Ruiz’s questioning of the Camp 7 Senior Medical Officer. Ruiz had called the witness to bolster his case that the session should be delayed because his client was in too much pain following the surgery. The judge allowed Ruiz to question the medical officer about the defendant’s current condition but not about how his past treatment at CIA black sites might be an aggravating factor. Ruiz and Pohl then engaged in one of the most tense exchanges of the pretrial phase – in which Ruiz criticized the commissions system as “disrespectful to the flag.” Pohl yelled when ordering Ruiz to sit down. (He eventually allowed Ruiz to finish his questioning of the witness.)

These defense efforts have not been fruitless. This summer, Pohl denied the defense team’s request to allow al Hawsawi to watch proceedings by video feed to Camp 7. However, after lawyers filed a supplemental motion on their client's health, the guard force decided to grant their request for a “special needs” van to transport al Hawsawi on his trips from the detention center to court and legal meetings.

Ruiz says he likely grew enamored with the idea of military service through his father, who was a military officer in Colombia before he moved the family to the U.S. when Ruiz was eight. Commission rules require capital defendants to have both “learned counsel” experienced in capital cases as well as military defense lawyers. For the first few years of the case, Ruiz, as a Naval Commander, wore two hats as both learned and military defense counsel – the only uniformed officer in the lead role. He is a reservist now in civilian clothes and said he occasionally misses wearing the uniform in court.

“I really wanted people to not forget that there were people in uniform who had sworn an oath to defend the Constitution, who are every bit as zealous, every bit as committed to the work we're doing defending this case,” Ruiz says.

Though a trial date has not yet been set, upcoming hearings could showcase a mini-trial of sorts as two defense teams challenge the commission’s “personal jurisdiction” over their clients. (The next hearing is scheduled for Dec. 4-8 with several more scheduled for 2018.) Before getting to trial, the government has to establish by a preponderance of the evidence that the defendants meet the 2009 Military Commissions Act’s definition of “alien unprivileged enemy belligerents.” Three of the five defense teams are waiting for additional discovery before making their personal jurisdiction challenges, but Ruiz has decided to push forward. The team for Ammar al Baluchi, led by James Connell, has also decided to make its challenge now. Prosecutors intend to show the two defendants supported hostilities against the U.S. and were members of al Qaeda.

Lawdragon sat down with Ruiz at Guantanamo Bay after the October session, which was cut from two weeks to one after the parties moved through all the motions ready for oral arguments. The session ended with one of the case’s signature twists – leading defense teams to assert yet again that the government is infringing on the attorney-client relationship – when Camp 7 guards seized the laptops of the five defendants over an alleged security violation. (The laptops hold case documents but are not connected to a network; the nature of the alleged violation was not discussed in open court.) Ruiz acknowledges that he may have annoyed Pohl again by arguing that the parties should stay for the second week to work through the issue and call government witnesses. Pohl refused.

Lawdragon: Looking back, almost a year later, would you say your client’s surgery was a success?

Walter Ruiz: I would say it’s mixed. If the definition of success is that it eliminates pain and discomfort, then no. From the perspective of reducing the size of the tissue, he doesn't have to do what he did before, reinserting skin tissue back into his anal cavity after having a bowel movement. So, yes, that's a positive thing. But in terms of the pain he experiences in the area, that's not completely eradicated. He's had additional hemorrhoids and additional fissures in the area of where the surgery took place. It still creates a lot pain and discomfort for him when he has to be moved. Getting the new vehicle for the transport has helped.

LD: How is his health overall?

WR: He’s not doing well at all. We talk about this as a team, in terms of his progression: When you start really low, you can’t help but go up from there. But when judging a male at the age of Mr. al Hawsawi, at 48, where they ought to be physically in terms of general health, he would definitely be on the lower end of the spectrum. He's got cervical injuries with bulging discs that have become degenerative over time. Then you couple that with ringing in the ears and hearing loss, sensitivity to light, chronic and extreme migraines, issues with kidneys and with blood in his urine without a definitive diagnosis of what's causing the bleeding. His sleep patterns have been erratic ever since the 2003 timeframe in CIA custody. He sleeps very little, and when he sleeps it's not quality sleep, which then of course causes him to have a much more difficult time recovering from his health problems.

LD: This issue seems to come up a lot – whether your client’s decision not to attend court is actually voluntary if he is doing so only for medical reasons. Is it ever voluntary with him or is everybody sort of just accepting a fiction to start proceedings on those court days?

WR: The judge, I think, certainly has incentivized us and Mr. al Hawsawi to engage in that fiction for the sake of him being able to stay in the comfort of his living area. I had this discussion with Mr. al Hawsawi because he doesn't want to be put through the transportation. Of course, I have the luxury of having the idealistic viewpoint that this is not the way it ought to be, that it's wrong for him to have to voluntarily waive his attendance because anything that he writes on the waiver actually calls into question the voluntariness. The judge has put him in that position and that has incentivized him to be dishonest about his condition, because if he is honest about his condition and it raises some real question of voluntariness, then the judge feels compelled to bring him to court in order to have that voluntariness inquiry.

The judge uses it to dangle over our head, almost in a threatening way, effectively saying: “Do you want us to just have him show up every day?” That really is not the way it should work. The way it should work is that, if there is a legitimate reason for him not wanting to come to court, the judge should allow him to fully articulate the reason. He then should address the issue as it comes up, but not engage in a fiction and certainly not threaten to take away the process he's put in place of defendants being able to not attend – just because it doesn't work the way he wants it to work every time. I found that very offensive. I found that to be very troubling and I didn't really understand it.

LD: Is your client able to participate in the defense in a way that you think is good enough?

WR: We don't have any questions about his competency. We haven't seen any of that, and his ability to communicate and engage with us, I think, is enough. The questions are whether he can watch and participate in court or to meet with us in an attorney-client meeting room for extended periods of time. When we do meet and talk, he has participated.

LD: Talk a little bit about your defense strategy, your desire to have him severed from this case. Why?

WR: It's the group mentality, the spill over. You see it often in court, not only when the prosecution speaks, but when the defense does as well, referring to the defendants as “these men.” The government has more serious allegations against other defendants but is using all-encompassing language in court. It’s a concern to us because we obviously want Mr. al Hawsawi to be judged based on the evidence against him – to have individualized justice. That’s very difficult when you have a group setting. We're very concerned ultimately about a fact finder being able to separate one piece of evidence against one person from one piece of evidence against another person, and not having that spill-over prejudice – the birds-of-a-feather and flock mentality, which is obviously what the prosecution wants to exploit and why they're fighting hard to keep it as a joint trial. [Editor’s note: At trial, the defendants’ guilt or innocence, and any sentence if there are convictions, will be decided by a panel of military officers.]

Mr. al Hawsawi’s case would move a lot quicker if he were severed. Obviously, you see the differences with our litigation strategy. We have a very different strategy in terms of how we approach things. Our strategy's not to delay. Our strategy is to get this to a point where it can be resolved because we think we have an opportunity to win. We have an opportunity to get a successful outcome for him and one that doesn't result in indefinite detention or life in prison or the death penalty. We really believe that we have a case that if we get it to a panel jury and they are faithful to the evidence, we think that there's a path for Mr. al Hawsawi either to go back home, sooner rather than later, or if he's found guilty of anything, that it would be a significantly reduced sentence. We want to get to that point because the alternative is for him to continue to sit here, without any kind of resolution. That's what drives us.

LD: You have pressed to get your personal jurisdiction hearing now. Three of the other defense teams are waiting until they receive more discovery. Why move forward now?

WR: We think we have what we need to win now – simple as that. We had other litigation strategies for filing this motion that have been served well. That’s about as much as I can say – that it has had the effect we've wanted. We're not here to survive, we're not here to endure. We're here to actually get to a point where we can have a successful outcome, and there's no need for us to push that day off. I understand the strategy of using this as a vehicle to try to get additional discovery, but it’s just not what we are trying to do.

LD: The al Baluchi team wants to call about 130 witnesses, many of them Bush and Clinton era officials whose testimony the team expects to undercut the government’s position that the U.S. was at war with al Qaeda on 9/11. You are taking a more minimalist approach by calling just one – Creighton Law professor Sean Watts. Can you preview what he will testify to?

WR: I'm not going to tell you what Professor Watts is necessarily going to say any more than I would tell the prosecution. But our position is that we were not in a state of hostility when the attacks of 9/11 took place. Our position is centered on the hostilities question. That’s why we filed the motion, that's how we framed it. Even though the rule has three different ways you can prove personal jurisdiction, each one of those has an element of hostilities. Whether you prove those elements or not, you still have to prove the existence of hostilities and we don't think the prosecution can. That is why we narrowed in on that particular prong and have said to the judge all along, "Judge, they can't prove the existence of hostilities – period.”

LD: When it comes to trying to get more information about what happened at the CIA black sites, you’ve mentioned in court that your client did not raise past treatment at the black sites to you. Your client did not complain to you; you learned much of it from the executive summary of the 2014 Senate report on the CIA and torture. Why is that?

WR: I've been so used to my clients wanting to tell me everything that's been done wrong to them: “The police did this, and the police did that,” and sometimes rightfully and truthfully so. But this was just so unlike that. I think it is cultural. I also think it was a matter of trust. For a long time, I was a military officer in uniform. From his perspective, he looked at me as somebody who is just an extension of the government, a citizen and a sailor. Why would he think that I would even care? I can absolutely see how I would just be seen as another government pawn who really didn't have his best interest at heart and wasn't going be there to listen and actually take action on what was done to him. I get all of that.

LD: Was there a time where that changed, that you can pinpoint, when he began to trust you? Do you think that doubt is still there?

WR: I would like to think that it's not, but I think it would maybe be foolish to assume that it isn't. I can't pinpoint it, but over time we've grown to have a greater degree of trust and respect. I think that's been just a gradual thing, battle by battle, issue by issue. He's seen me take some hits in court, and I think that's helped the relationship. I do think that every time you have a government intrusion, like the one this week [with the seizure of the laptops], I could imagine there being this uncertainty: Is this person really who they say they are? Could I be a CIA plant? It wouldn't be unreasonable for someone in his position to at least question that.

LD: Have you been able to get more information about his time at CIA black sites?

WR: Yes, we have been able to get additional details from him. Really, the Senate report was a conversation piece, for lack of a better term, because it allowed us to say, "Hey, can we talk about this stuff?"

Another part of it is that because the treatment was so brutal, there are just gaps in his memory. The whole point was to disorient him, so there are gaps in his memory in terms of what he remembers or the amount of detail. The reason we still continue to litigate for more information on that front is because I think it's totally reasonable that even if he was conscious for a period of time that things were happening, he wouldn't remember all of it. But maybe they were documented and that would give us additional insight.

LD: You had a big motion to dismiss this case based on national security reasons – that the national security concerns of the government are preventing a fair trial. Did you ever give closing arguments on that?

WR: The judge ruled against it on the pleadings and didn’t actually give us a chance to argue it. But it’s just a heartbeat away from being revived, especially after this week.

LD: Can you talk about what your reasoning is on that motion?

WR: At the very beginning of this process, one of the recommendations that the charging official had to undertake was: Can this case be tried fairly in accordance with due process and still be faithful to national security considerations? The advice was yes, but what we've seen from that time on is the tension between due process and national security concerns. You can't have national security thwart the due process. At that point, you've got to make a call, and the call has to be: "We're going to protect national security but we can't try this case. Because we are not willing to give up certain information.”

Gen. Martins [chief prosecutor, Army Brig. Gen. Mark Martins] at one point made the statement that the government is never going to give us the actual location of the black sites, and they are never going to give us the identities of people who were torturers. Even if the judge ordered that, they would absorb whatever the appropriate sanction is rather than give us the information. That’s the inherent tension between having a fundamentally fair trial and national security concerns. How in a capital case do we properly investigate what is essentially a crime scene? You won’t give us the actual location of the sites, or the identities of the torturers so we can do our own independent research and background analysis. When you continue to assault the fabric of a fair trial, and the justification is national security – the trial has just got to go away. That’s what we’re highlighting.

LD: If judge Pohl changes his mind and later decides that the defense should get the locations of the sites and identities of interrogators – and the government says “No, we’ll accept the sanction” – what should the sanction be?

WR: Dismissal. Dismissal with prejudice.

[Editor’s note: Pohl has approved the government’s proposed summaries and substitutions of the original CIA evidence, which does not include details on site locations. Defense teams have filed additional discovery motions including those seeking locations of the black sites.]

LD: You’ve had your moments where there’s been this push and pull of possibly leaving the case, as a protest to the system, but that would likely leave your client in a worse position. But by staying on you’re helping to legitimize a system you don’t like.

WR: I have thought long and hard about that. We're greasing the skids, we really are. When you think about it, we as defense lawyers are essential to the process and probably one of the most important cogs in the machinery. I do think that if tomorrow I was not on the case, they would find another cog and stick it in the machinery. It may cause a delay, but I think this beast and this machine is built to convict and to kill. That's what it's built for and taking me out of it may for a moment stop the process, but ultimately they would plug in someone else and it would just extend the process. If I really thought that my withdrawing from this case would mean the end of it, then that's a different analysis, but I don't believe that.

Some ego and personal pride factors into the decision as well. I'm sure there are lots of other professionals who would step in and do a good job, but I know that I would do it the way I would do it, so there's that control aspect. There's also my personality, an aversion to leaving anything that I start unfinished, even to my detriment many times. I'll start reading a book and feel compelled to finish it even if it’s horrible – just because I started it.

I do not think that I'd be able to live with walking away from it as unfinished business and feeling that I didn't finish what I started. I'm committed to seeing it to completion. I think I owe it to the case. I owe it to Mr. al Hawsawi. I think I owe it to principles of justice, if you can say that. Maybe even ideals – the ones I still have left and [with a laugh] that haven’t been beaten out of me over the course of time. Then, maybe a slight, faint, foolish hope that there is light at the end of the tunnel, that this case can be meaningful. Not just in terms of what happens to Mr. al Hawsawi, but in terms of what it means for us as a people, as a nation, and the evolution of justice and the way we engage with these kinds of things that happened. All of that makes me want to continue to, for lack of a better term, endure. Endure this process.

LD: There seems to be more tension between you and Judge Pohl. Has that entered your mind and how do you manage that going forward?

WR: There's absolutely, in my view, more tension. It has entered my mind. I don't intend to manage it. This is a situation where I don't think this judge is going to do us any favors. I think the longer the case has gone on, I've lost confidence in him as a jurist. Three of the fastest decisions he's ever made have had to do with his personal comfort.

[Editor’s note: The judge cancelled the July hearings after learning that leadership of Joint Task Force Guantanamo had ended the fast-boat service that takes him and his staff from the air terminal to the main part of the Naval base, separate from others who ride a ferry. Pohl determined that the process that had been in place for years was necessary to prevent “unacceptable commingling” between the judiciary and the other case lawyers, victim family members, media and NGOs who ride the ferry. The separate fast-boast service was restored before the August hearing.]

When they changed the method of transportation across the bay, he stopped all of the proceedings. But when I had asked to abate the proceedings, it was shortly after Mr. al Hawsawi’s surgery. He had just had a pretty invasive surgery and I was asking for a delay – or at least for him not to have to come to court on the first day. The judge wouldn't do that. I take that and I put in in the context of he's going to abate the entire proceedings for his boat. What does that say to me? What that says to me is that he cares more about that than he does about Mr. al Hawsawi’s health.

So, there's been a couple of times that got pretty heated. I don't see any incentive for saying things any other way than the way they are. I think for 99% of the time, I've done that respectfully and with due deference. I don't believe in sugar coating it with "Yes sirs" and "No sirs.” I always call him “judge” and I think have an appropriate dialogue with him. He's not the first judge that I've crossed that path with. I feel comfortable that I'm doing what I need to do to represent Mr. al Hawsawi and I'm not going to water that down because I'm somehow worried about managing that relationship.