The road to greatness was not easy. In 1998, when Outten & Golden opened its doors, it was a Mom-and-Pop shop, comprised of the two founders, Wayne Outten and Anne Golden, plus Wayne’s wife Ginny handling administration and one other lawyer. Golden and Outten had worked together for several years at Lankenau Kovner & Outten.

Outten used his payout from his previous firm and a home-equity line of credit to pay the bills for the first few years. It was a gamble, fueled by Outten’s determination to create better representation – and rights – for workers.

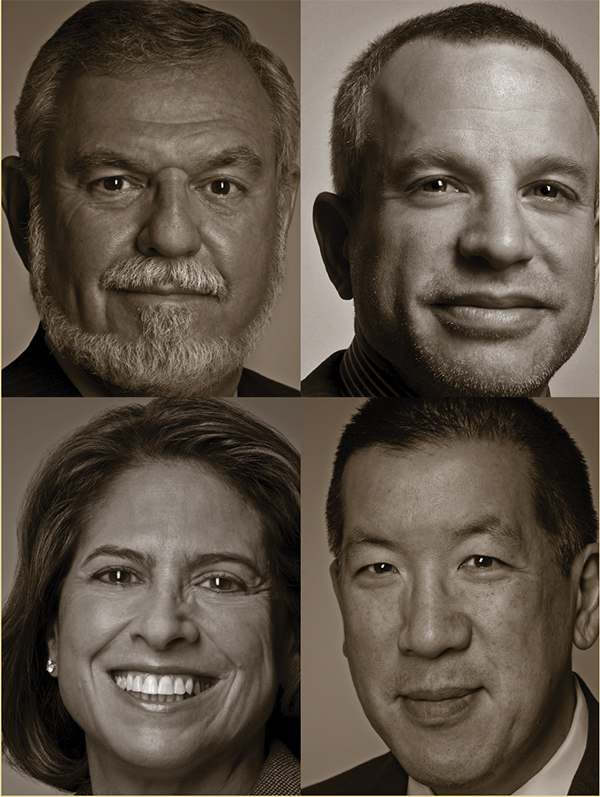

The firm focused initially on representing individual employees in all areas of employment law, including discrimination, retaliation and contractual agreements. In 2000, the firm started a fledgling class and collective action practice – led initially by Adam Klein – forging new frontiers for workers’ rights and fighting against wage theft as well as gender and other forms of discrimination. During the ensuing years, Outten & Golden grew to become the nation’s largest employee-side employment firm, whose two complementary parts together created much more than one whole.

Wayne Outten served as Managing Partner until the end of 2018, when he became Chair and Adam Klein became the Managing Partner. Anne Golden retired in 2015.

A tireless and surprisingly soft-spoken titan, Outten fell into representing employees by writing a book about employee rights. After college, he was supposed to rejoin the family furniture business (Outten Brothers in Pocomoke City, Md.). But as he came of age during the late ‘60s, he saw a different path for himself.

“As a product of the time, the reason I became a lawyer in the first place was to ‘change the world.’ I didn’t do it to make a big living. That is why, while I was in college, I shifted directions and decided to become a lawyer,” says Outten, who graduated from Drexel University in 1970 with a business degree. “The people making things happen then tended to be lawyers or preachers – and I knew I didn’t want to be a preacher.”

He enrolled at New York University School of Law because of its focus on public interest law, and he met Norman Dorsen, the head of the ACLU and a professor and champion of civil liberties. Dorsen was editor-in-chief of a series of handbooks on individual rights; and in 1978, he asked Outten to write “The Rights of Employees.”

Though he had never even taken a course in labor or employment law, his path was laid before him. “Most people become an expert in something and then write a book about it. I did it the other the way around,” says Outten. “I knew nothing about the subject when I started the book. Literally nothing.”

Starting in 1979, he spent the next two decades at Lankenau Kovner becoming a leading advocate for employees.

“I happened to be in the right place at the right time because, until the ‘70s, there really wasn’t a body of what we now call employment law,” says Outten. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 laid the groundwork for civil rights in employment; the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 provided some protections for older workers and job applicants; the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (the year Outten graduated from NYU Law) set standards for retirement and welfare funds; the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed in 1990; and the Civil Rights Act was amended in 1991. These and other laws enhanced the rights of minorities, women, the disabled and other employees.

Although employee rights were expanding, financing a firm that would solely enforce those rights was scary. “I was 50 when I started Outten & Golden. I wanted to build and grow a public interest law firm representing employees, based on sound business practices, that could go toe-to-toe with any employer-side firm in the country. From age 50 to about 57, I never worked harder in my whole life,” recalls Outten. “I was generating the bulk of the money initially and I sometimes had to lend money to the firm to meet the payroll.”

Outten & Golden’s potential began to come into focus on January 1, 2000, when Klein, a far-thinking and determined advocate, joined. He set to work creating the class-action practice that has come to define a major part of the firm’s mission.

Its partnership is a model of diversity in law practice. Sixty percent of the firm’s partners are women, and more than 20 percent of its partners are Black, indigenous and people of color, or BIPOC; three of the seven members of the firm’s Executive Committee are women. The firm has developed a team of about 55 attorneys, with offices in New York, Washington, D.C. and San Francisco, creating a corps unmatched in its national impact.

Its civil rights practice represents the alchemy that extends its reach and defines its mission. A virtuous circle is created by the funding from its long-term successes in class actions, which in turn are bolstered day-to-day by its representation of individual employees and executives. The firm’s lawyers choose to make less by donating generously to civil rights and workers’ rights organizations, while also serving in leadership positions in organizations that seek to do the same.

“We have a real presence within the community of civil rights organizations of people who are serving the community’s interests in a way that’s impactful,” says Klein, who until recently was Co-Chair of the Executive Board of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. “That’s a real part of our DNA; that’s important to us. It’s not just pro bono work that we do because the bar requires us to do it or because of good corporate citizenship. We’re doing it for a different reason, completely different reason. It’s who we are.”

Among the firm’s voluminous contributions to civil rights, Klein led the landmark lawsuit against the Census Bureau that challenged the use of arrest and criminal history records – or any interaction with the police – to screen out approximately 500,000 Black and Hispanic applicants to be enumerators for the 2010 census. In 2016, the federal government settled the case, which led to fundamental reforms in the hiring process for future applicants and creating a class-member Records Assistance Project.

While Klein leads the discrimination unit of the class-action practice, Justin Swartz generally calls the shots on wage-and-hour cases, which Outten & Golden was among the first private firms to take to federal court.

“We started by filing some lawsuits on behalf of low-wage workers in the grocery store industry, the bank call-center industry and the restaurant industry,” says Swartz, who joined the firm in 2003. “What we realized was that there was mass non-compliance across those industries and others and that there’s a real need for private enforcement, because the government enforcement agencies like the federal and state departments of labor – despite all good intentions – were not sufficiently resourced or staffed to even make a dent in the need to enforce those laws.”

Over the past two decades, workers’ claims and employers’ efforts to insulate themselves from costly fallout have morphed into what Swartz calls a “game of cat and mouse.”

“The employers’ bar comes up with new ways to cheat workers, obscure their violations, or keep workers from enforcing their rights, and the plaintiffs’ bar figures ways around that,” he says.

“The most recent example is forced arbitration,” Swartz adds. “More and more employers have forced their workers to agree to resolve any dispute that they have with the employer in arbitration, as opposed to court, which in many cases effectively renders the employee’s rights unenforceable because arbitration is a difficult, expensive process that is weighted in favor of employers.”

Among Outten & Golden’s successes in wage-and-hour cases is a series of cases filed on behalf of unpaid interns that helped level the playing field between college students and recent graduates from relatively privileged backgrounds – who could afford to work for free – and lower-income peers who couldn’t.

“These cases were important not just because they ended up with workers getting paid, but also from a social justice perspective, because unpaid internships have always been a ticket to highly paid jobs,” Swartz says. “Our efforts have resulted in a lot of companies paying their interns, and that opened up internships for people who couldn’t afford to work for free, including people of color and people from economically disadvantaged backgrounds and anybody else who needed money for their labor. That was particularly satisfying.”

But like a literal pipeline that must be laid, there are years of, well, laying pipe, before any oil flows. “In the early years, we could not find adequate capitalization,” says Klein, “which is a fascinatingly difficult barrier to entry.” Without it, the firm was taking on employers defended by the biggest, most well-resourced law firms around. “With fewer than 20 lawyers, it was hard to compete.”

But somehow, they did. Because sometimes nothing succeeds like passion fueled by determination and necessity, plus excellent lawyering and the strong merit of their cases.

Laurence Moy, now the firm’s Deputy Managing Partner and co-head of the firm’s Individual Practice Area, brought 18 years of experience in financial arbitrations (including 10 years at a plaintiff employment competitor) when he joined in early 2004. He also brought the life experience of working in his family’s Nanuet, N.Y., Chinese restaurant and a side passion as a pool shark and author.

“I worked in the Chinese restaurant as a dishwasher and a waiter. My sister worked up front. My mother worked seven days a week – she worked full time during the week as a customer service supervisor for the local utility company and at the restaurant on weekends. My dad worked six days a week. By the time I became a lawyer, compared to what we did at the restaurant, I didn’t think the hours were so bad.”

“I always felt like I’d rather be on the side that’s pushing to level the playing field,” says Moy, who had advocated before FINRA and the NASD regarding exits, compensation, discrimination, you name it.

Larry, the name he usually goes by, has built a tremendous practice advising individuals, particularly in the financial world, in a range of disputes. Among his achievements are a $70M arbitration award in an international arbitration for a group of finance employees and an $18.9M arbitration for two finance executives, two of the largest arbitration awards in employment cases.

The case that boosted Outten & Golden’s future came from a client Outten counseled in 1998, a former Morgan Stanley institutional equity saleswoman, who alleged that she had been denied promotions and pay commensurate with her male colleagues.

Working with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Outten – with Klein’s key assistance – transitioned that individual discrimination case into a case involving 340 women. In 2004, after years of battle, Morgan Stanley paid $54M to settle the case on the eve of trial (including $12M for the lead plaintiff), resulting in the first relatively substantial fee for the firm.

Exhale. Briefly.

When Wendi Lazar met Wayne Outten around that time, she found synergy and admired his vision for Outten & Golden. She had her own successful boutique law practice representing individuals and small companies in business, individual employment and immigration. Early on, she represented women in sexual harassment cases as well.

When Outten invited Lazar to consider joining the firm, Lazar was concerned because she’d have to give up her corporate clients. It’s Law Firm 101 that, to make money, you need to represent corporations, or at least have a reliable base of hourly or other predictable revenue.

But it was worth the risk because Outten and Lazar were forging a different path. Representing high-level executives domestically and globally in negotiations and transactions is a highly valued service. And “you can do well while doing good,” Outten told Lazar. He has said that so often over the years that it became the firm’s mantra.

Lazar brought an executive compensation and employment practice to O&G, with a healthy dose of entertainment, advertising and media clients. She also continued to take on gender discrimination cases.

With Outten, she realized, they “could build a larger combined practice for executives and talent. We would be as good as any of the large firms and able to produce excellent work for executives on the level of a Simpson Thacher or Paul Weiss…we could build a practice and brand that really gave executives another alternative,” she said.

“Wayne and I were probably the only employee-side lawyers on the East Coast who were dealing with individual representation of talent on a global basis, especially multi-national executives,” she said.

The firm’s Executives and Professional Practice Group, as it is known, is without much competition among employee-side firms, especially with its focus on a problem-solving, strategic approach. For many lawyers, financial professionals, private equity players, founders selling their businesses and female executives, there is only one call to make when they need help. And it is to Wayne or Wendi – or one of their other practice group colleagues. “We understand their world,” says Lazar.

That practice fits nicely into the firm’s public interest mission. “Our civil rights work is definitely on everybody’s mind. It is the glue that binds all of us,” says Lazar. “No matter whether we’re representing CEOs or undocumented workers, getting our clients what they deserve is our priority,” Lazar says.

As of January 2019, Jahan Sagafi, Tammy Marzigliano and Ossai Miazad became equity partners of the firm.

Marzigliano, who is a national leader in representing whistleblowers, among other workers, joined the firm in 2004. Like her partners, she is passionate about the law and takes great pride in her representation of her clients. “Often times my clients just want to be heard and I give them that platform – when they cannot speak for themselves; I speak for them. When they cannot fight for themselves; I fight for them.” Marzigliano believes that “every worker should be treated with dignity and respect.” She not only co-chairs the firm’s Whistleblower and Retaliation Practice Group and its Financial Practice Group, but she also is a member of the firm’s Sexual Harassment practice, where she is often struck “by the imbalance of power in these cases” and the “utter disregard for the law.” It is good to be on the “right” side of these issues.

“What drives me every day is that I have the ability to help people and make a difference in their lives. What’s even better is that I get to practice in a place with like-minded caring people,” says Marzigliano.

Like Klein, Moy and Lazar, Marzigliano has been there for the good times, as well as the rough ones, and understands that, with growth in the size of the firm, “You may lose intimacy, but you also get to meet amazing, brilliant people and to do great work with them.”

Sagafi leads the San Francisco office, which he opened upon joining from Lieff Cabraser. Another member of the firm’s class-action powerhouse corps, he has recovered more than $100M against companies including Uber, Hertz, IBM, Wells Fargo, Walmart and Farmers Insurance. Most recently, he’s been working on gender and racial discrimination and harassment in the tech industry.

He followed in the footsteps of his mother, who worked at the EEOC and then as a sole practitioner representing employees. She met Sagafi’s father while serving in the Peace Corps in Iran. Sagafi was raised Quaker, “steeped in the moral principles of equality and the fight for justice, and the civil rights movement,” he says.

When he decided to join Outten & Golden, he was impressed with the firm’s work, “but the most important part was just that they are good people. I didn’t know Wayne at first, but I knew Adam and Justin and other folks from the ABA and from co-counseling.”

Miazad, who co-chairs the Discrimination and Re-taliation practice group, was a key member (along with Klein) of the team on the Census case – work for which the group earned the Public Justice 2017 Trial Lawyer of the Year Award.

Miazad, herself an immigrant to the U.S., is leading the firm’s class action discrimination cases on behalf of Dreamers. “There is real value placed on innovation and thinking outside the box which makes this firm an incredible place to work,” she said. She is motivated, in part, by the impact that creative lawyering can have on chipping away at structural barriers to equality. She is co-chair of the firm’s Equity and Engagement Committee. “I am deeply aware that there are very few women of color who rise to equity partnership in law firms. I am excited to be in the room and to bring new perspectives,” Miazad added.

The firm’s partners are remarkably of one mind about its values – which is especially impressive given their diverse backgrounds. To a partner, they share a belief that their individual compensation is not their measure as lawyers or as people. Instead, it is making enough for a good middle-class lifestyle and contributing to workers’ rights that is the goal.

“We’re not trying to maximize everyone’s net worth. Because people here are smart enough that they could’ve gone into investment banking, if money was all they had in mind,” says Moy. “That’s why we get a talent level, especially from our newer lawyers, that almost we don’t deserve. It’s unfair. Because for the people who come here, it’s a calling for them to get involved in work that has a public interest dimension and a civic dimension.”

There are lessons in Outten & Golden’s story of passion, dedication, decency and commitment to something beyond oneself. There is also – and this is important – that rare non-cautionary tale of what can happen when someone steps away before his or her partners wished it were so.

Outten talked about his transition and the craft of moving on more than two years ago, as he ate a salad at his desk in Midtown Manhattan. He showed a photograph of a marvelous country house near Ocean City, Md., where he was going that Thursday afternoon for a long weekend.

After more than 40 years representing workers, he is practicing his own advice with a rare self-awareness that to stay would not only be gratifying his own conceit but also would be robbing those he brought into the firm of the opportunity to advance in their own field. In the firm whose doors he opened (and which bear his name), he won’t be the one to turn out the lights.

The transition from Outten’s “create it and grow it” era to Klein’s methodical running of a mid-size business with a powerful practice began in 2018 as Outten approached 70.

Golden, Outten’s co-founder, had retired three years earlier, after leading the firm’s Discrimination and Retaliation Practice Group. During her career at O&G, Golden earned the respect of both management-side and employee-side lawyers as a gentle but firm advocate for her clients. She represented employees in trials, appeals, mediations, arbitrations and negotiations in every aspect of employment law; she litigated groundbreaking cases involving summary judgment, retaliation and attorneys’ fees; and she negotiated many agreements on behalf of executives and other employees. As she approached retirement, the New York affiliate of the National Employment Lawyers Association awarded Golden its highest award.

As part of his plan to hand over the reins, Outten launched what he called O&G 2.0 to examine and re-create every aspect of the firm – from finance to technology to benefits – to build a solid new foundation for the next 20 years, with a particular focus on leadership and management.

Since January 2019, Adam Klein has been the Managing Partner. In truth, the transition had always been in place as Klein helped build the firm from the outset and always had his eye on the future.

“So much of the credit goes to Wayne for always having in mind preserving a legacy by letting go. Like he always had in mind the transition. He could’ve easily continued to be the dominant figure in the firm for as long as he wanted,” says Moy. “And I think that would have created a different legacy for him. But instead he had the long view. He created something that’s going to outlive us all. It comes from his wisdom and unselfishness.”

The Covid pandemic presented major challenges for everyone during 2020, including O&G and its clients. The firm’s offices were closed, and the progress of cases was delayed as the courts shut down and or dramatically changed their procedures. Meanwhile, the firm’s clients needed help navigating the changed workplace.

The firm’s leadership responded in a deliberate and compassionate manner to address the interests of its people and its clients. Among other things, the firm created an internal taskforce to figure out how to help clients, which included adding substantial information to its website to inform workers about their rights. The transition to remote work for everyone worked quite well and will continue as long as necessary to protect its people. The firm’s lawyers adapted to the changes in the practice of law, including virtual mediations and depositions and client conferences by video.

As he planned his gradual transition out of firm leadership, Outten considered the importance of the firm’s culture. It was the entire focus of the last all-attorney meeting he led as Managing Partner; and that culture may – perhaps more than even the astounding impact on workers’ rights he has created – ultimately define Outten & Golden. For, it turns out, if you really believe in and make your living from advocating for the rights of workers and for better workplaces, there is no place like home.

“To be immodest, I envisioned and molded the firm culture,” says Outten. For the firm’s first 20 years, he personally participated in and made the job offer to every single lawyer hired. His criteria from day one were threefold:

First, the lawyer must be smart and industrious with good judgment – someone who can provide excellent service for every client. “But that’s not enough,” Outten says.

Second, the lawyer must have a passion for Outten & Golden’s cause. “They want to help people. It’s not just a job. It’s a mission,” says Outten. “We’re a civil rights firm; we’re a public interest firm. So, everybody who comes here must come here because what they really want to do with their legal skills and as a professional is to help people – to help employees specifically – and to help improve the law, to educate workers and to advance their interests on a one-by-one, person-by-person basis, on a class basis and systemically and societally.”

Third, every lawyer (and every other person who works at the firm) must be a nice person. While hard to measure, “it’s not as hard as you might think. Somebody can have the greatest credentials in the world and really, really want to work here; but if the person is a jerk, we’re not going to hire or retain that person,” says Outten.

Firmwide, and especially in the leadership ranks, there’s a recognition that the values Outten & Golden fights to uphold in court must be reflected in its own offices. “We’re advocating for clients to have a fair workplace, to be treated with dignity, to have outcomes that they understand and for them to be treated with respect and not discriminated against,” Miazad explains. “So, the firm itself can’t work any other way. We wouldn’t be able to survive that kind of hypocrisy.”

Indeed, Outten says, the firm’s mission is “excellence and integrity above all else” – all work must be done with integrity.

“Nobody’s allowed to cut corners. We say, if anybody gets close to any ethical line, then they’ve gone too far. We’re known for that out there in the world – that we’re responsible, that the lawyers here will tell the truth and that the lawyers here will be honorable,” says Outten.

Outten’s path over the past few years is heartening in a world of “hanging on” as a public art form among those who – for many reasons – can’t walk away. It’s a funny transition. Outten and Klein are not alike, but Outten does not try to shape Klein in his own image. Which would not be possible. Which is another part of the transition lesson: For founders who believe that only they, or someone in their image, can carry on, shouldn’t you ask what it is you’ve created if it’s still all about you?

Outten is quiet, still, even. Klein is also on the low-decibel end of the spectrum, but the energy that jumps out of his head is a chaotic symphony. Klein is co-lead plaintiffs’ counsel in a long-running gender discrimination lawsuit against Goldman Sachs. He also is focused on the use of technology in hiring practices, “gamified psychometrics” by which companies replace interviews and longstanding hiring protocols with video games that purportedly measure instincts and other values that allegedly correlate with hiring.

Klein was raised by a father who ran a motel and a mom who worked at a local newspaper in Riverhead, N.Y., a working class Long Island town. They were relatively poor, and he observed early on the difference in outcomes from those with more resources. That underdog sense fueled his success as a litigator – and now has made him an astute leader of Outten & Golden.

“The practice of law has radically transformed. In a way, it’s sort of like a driver-less car relative to, like, a Model T Ford,” he says. Klein’s made it his mission to transform the firm for whatever comes next.

“We hit that button after realizing there’s no way to grow people internally that would have the skill set. We cannot just rely on our talent. It doesn’t work,” he says. “We’ve learned that you need a mix. You need homegrown talent and to retain your talent. But you also sometimes have to bring in external talent.”

He is unafraid of the challenge of the future; and as a civil rights litigator, he has seen that “a common thread of successful people is that they ignore their failures.”

“I often think about our firm challenging normative behavior,” says Klein. “What was tolerable then, becomes intolerable and offensive now. There are so many contemporary examples of the firm leading the charge on addressing social ills in the workplace or with other aspects of our society. I wake up every morning thinking about what we are missing – how can we make the world a better place. I wish everyone had that type of career.”

Outten & Golden has been the beneficiary of traits Outten passed along from his parents, both of whom grew up in large farm families during the Great Depression. The business savvy of his father (Norris Outten) is reflected in the firm’s business-like approach to running a public interest law firm. The kindness and decency of his mother (Marie Perdue Outten) is reflected in the firm’s culture; Outten has imbued the firm with “Perdueness” – a salt-of-the-earth genuine nature.

Pass it on.