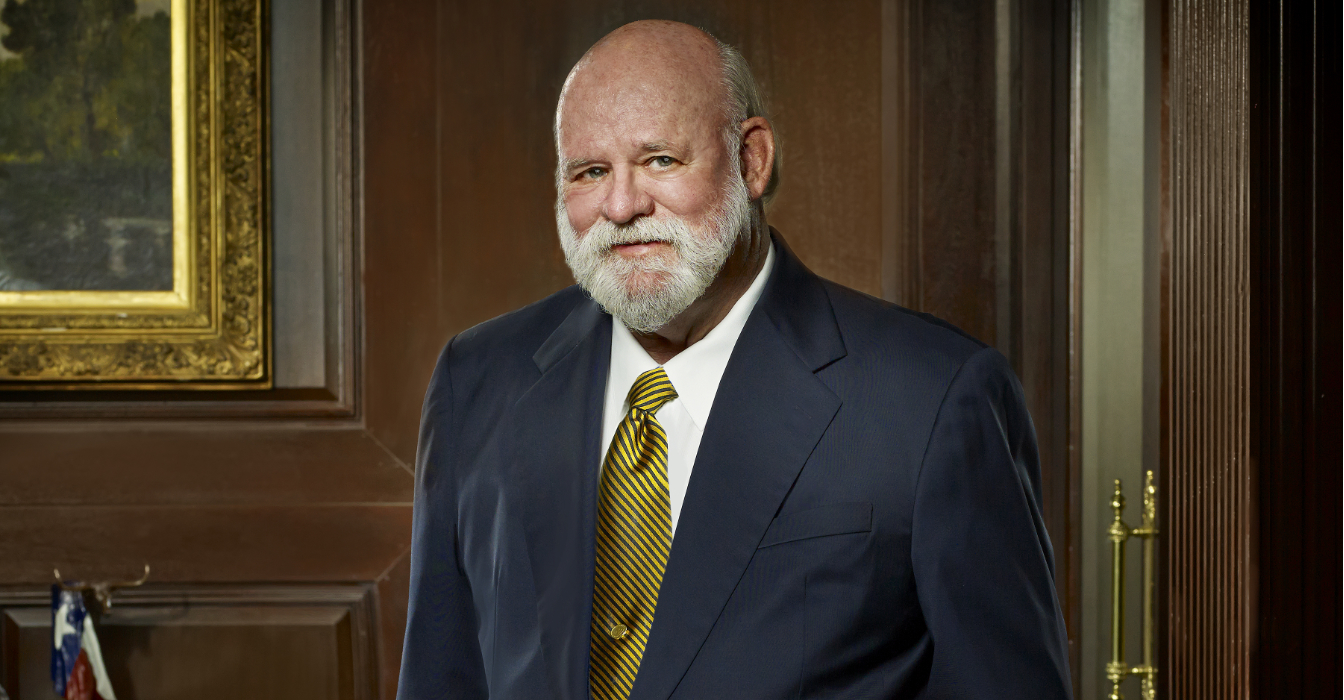

Frank Branson was in law school when he got hired as an independent insurance adjuster. The job offered the young student a sobering peek behind the curtain – a direct view of the complex machinations of the insurance industry. He saw, up close, the treatment victims were given by a system that was designed not to make them whole after catastrophe struck, but to save the insurance companies money wherever it could.

That experience became Branson’s super-fuel as he headed back to get his Masters of Law in legal medicine. His motivations now were crystal clear – he wanted to give victims a fair shot in the system. And Branson, using the insight he gained in the early days along with a vast toolkit he’s assembled over the years, has had major success doing just that since he began his practice in 1969.

In his expansive and monumental career, Branson has secured record-setting jury verdicts and jaw-dropping settlements for injured victims and families in a wide variety of cases, making Branson one of the most respected trial lawyers in the nation. He has been behind some of the most highly impactful personal injury cases in the country, cases that have shaped laws, re-structured industries and offered his deserving clients significant financial compensation. And while he has seen the insurance industry change, grow and reform to some degree, Branson believes that more can – and should – be done.

“I think that the emphasis has been on the wrong syllable,” says Branson, a member of the Lawdragon Hall of Fame. “Instead of attacking the people whose lives have been devastated by corporate and medical misconduct, if the insurance companies had spent the money to improve safety and their product, I think we'd have had a much better result for the people.”

At The Law Offices of Frank L. Branson – where Branson works alongside his wife and partner Debbie Dudley Branson – the firm is committed to their clients. They spare no expense when it comes to resources for each and every case. From experts, nurses, investigators to generating computer graphics or enlisting professional illustrators – there are no bounds when it comes to building the strongest case for their clients who are suffering.

“We've been fortunate beyond our wildest dreams,” says Branson. “Mostly, we've helped an awful lot of really good people who were badly in need of help, and because of the size and power of the defendants that caused their injuries, it was hard for them to deal with the system without a lawyer who would fight for them.”

At Lawdragon, as we look back on 20 years, it’s distinguished advocates like Branson who remind us just how far we have come and galvanize us as we look down the road ahead.

Lawdragon: How have you seen the practice of personal injury law change in the last 20 years?

Frank Branson: Juries in the Dallas area have gotten better. When I started practicing in 1969, Dallas was one of the most anti-victim counties in the state. It has since developed into being a fair county to try lawsuits in – on both sides of the docket – but it's much better for victims than it was when I began. I've felt the change throughout Texas, nothing hugely dramatic like in some of the other states, but when I walk into a courtroom in a trial lawsuit in Texas, I find a warmer environment for the injured party than I did back in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

LD: What do you think accounts for that?

FB: Well, there is a tremendous increase in empathy and understanding today than from how it was in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Not just juries, but the population in general have become more empathetic because they've had access to more information. The national press has been a big factor in illuminating some of the problems with corporate America and the insurance industry. The media has given them more information about some tragedies that have occurred, so there's a bigger diversity of views. People in general have become more aware of consumer issues.

There is a tremendous increase in empathy and understanding today than from how it was in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Not just juries, but the population in general have become more empathetic because they've had access to more information.

When I started practicing, the jury pools in Dallas had been historically drawn from property ownership. About a decade into my practice, they changed that to a driver's license, and that made a tremendous difference. Now, the jury panels are much more reflective of my clients.

LD: That makes sense. Can you tell us about some of the clients that you're currently working with?

FB: We always have a wide variety of clients. We currently have a client who was on a private toll road. These tolls were implemented, supposedly in part to keep the toll road free of ice and snow, or if it got too bad, it was meant to stop people from coming on the road. Our client was a businessman in his late forties, he came from a family of educators. His wife served as a superintendent in one of the school districts in the area. He was let on the toll road, which he should not have been. There'd been a serious accident three hours before. He came upon an icy portion of roadway, he couldn't stop, piled into the back, and then an 18-wheeler traveling way too fast hit the back of him – and that caused his death. It turned out there was no question the tollway had culpability, as did the truck driver. He left behind a wife and two children – a really nice family.

We had another case involving a man working on an oil rig and there was an oil blowout. He's about eight feet off the ground and is knocked off the rig, and as the oil and pipes come down from the blowout, they hit him on the head causing brain damage and a neck fracture. In that case, there's no question that safety precautions on the rig had not been followed and should have been.

Currently we're also working with a nurse who had a growth on her vagina that the doctors wanted to remove. The intent was to remove it with 4 percent acetic acid, and the nurses somehow brought the surgeon 100 perfect acid, due to poor storage practices at the hospital. This caused the victim severe burns throughout her vaginal area. She has since had trouble standing and sitting and has had to give up nursing.

LD: You really have a wide variety of tort cases. Looking back to when you started your firm in 1978, does it look today like you envisioned it back then?

FB: It does. We've been very fortunate. I trained in a firm that handled a large volume of smaller vehicle accidents and workers' comp cases. When I began my own practice in 1978, it was my hope to be able to move to a wider variety of types of injuries and to represent more severely injured clients. I think we've done what we hoped we could do.

We've had multi-million-dollar trial jury verdicts and settlements in cases involving commercial plane crashes, trains, automobiles, buses, trucks, healthcare providers and products liability. We've been fortunate beyond our wildest dreams. Mostly, we've helped an awful lot of really good people who were badly in need of help, and because of the size and power of the defendants that caused their injuries, it was hard for them to deal with the system without a lawyer who would fight for them.

LD: You've been practicing law with your wife all this time, tell us about that.

FB: It's been really good for us. I don't know that all husband and wives would be compatible enough to do it, but Debbie and I work very well together. She grew up in the law, her dad was on the Arkansas Supreme Court. She's got a master's in psychology and is enormously helpful in voir dire and throughout the trial. We've tried nearly every lawsuit that I've tried for the last four decades, together.

LD: Do you have advice for other married lawyers who might want to work together?

FB: You have to be able to rely on each other's strengths, I think you have to be personally compatible – I'm not sure all married folks are. You have to respect each other’s abilities. Debbie's stronger in some areas than I am, and it gives me another set of eyes in the courtroom to pick up anything I may miss.

We've helped an awful lot of really good people who were badly in need of help, and because of the size and power of the defendants that caused their injuries, it was hard for them to deal with the system without a lawyer who would fight for them.

LD: What stands out as the most challenging case of your career?

FB: Probably a case I tried back in 1984 – Birchfield v. Wadley Hospital. During the ‘50s the leading cause of blindness in children was something called retrolental fibroplasia (RLF). It pretty much had gone out of the medical literature by the early to mid-seventies, and was no longer the leading cause of blindness in children in the country, but there still were some of those cases.

A hospital in a very conservative part of the state had a series of babies who were blinded. What happens in RLF is some of the later developing vessels in the bodies are small retinal vessels. If premature children receive too much oxygen, the oxygen content as it goes through those vessels, obliterates the vessels, causing blindness. That happened to a young lady named Kelly Birchfield.

The community we tried it in was a conservative community without a history of large verdicts. The hospital and the pediatric group were the largest in the area. There was a lot of local sentiment in favor of the healthcare provider. During the trial, the healthcare providers would send nurses down throughout a long trial to sit and stare at the jury. The doctors hired a lawyer from Little Rock, Arkansas named Bill Eldredge, who had tried cases for 30 years and never lost. Debbie went to some friends in Arkansas and gathered up some of his jury arguments, which allowed us the opportunity to preempt a lot of what he did during the trial. It helps in trying lawsuits sometimes to get a scouting report the same way football coaches do on other teams. That was a very difficult, long trial, and it worked out for us. The verdict was a nice verdict. It was appealed to the Supreme Court, and we won it.

LD: Do you remember the number?

FB: I think it was $6.9M back in the mid ‘80s.

LD: That's great. Our justice system has taken some hits in recent years – from forced arbitrations, damage caps, and the politicization of our judiciary. Tell me if you agree, and more generally, what would you like to see in order to keep our trial courts strong for citizens?

FB: First of all, I very strongly agree with that. I think our courts have continued to be a bastion of protection for citizens, but certainly some of their protections have been taken away – forced arbitration is terrible. I really think if the doctors, and hospitals, and trucking companies, and manufacturers would spend the tens of millions of dollars they've spent trying to get tort reform to keep them from having to pay for the catastrophic injuries they've caused, I think if they spend that to improve their product, it would do a lot toward adding safety to our communities.

I think that the emphasis has been on the wrong syllable. Instead of attacking the people whose lives have been devastated by corporate and medical misconduct, if the insurance companies had spent the money to improve safety and their product, I think we'd have had a much better result for the people.

LD: Speaking of which, are there particularly meaningful wins of yours that have added to the general safety of products, procedures, or services?

FB: We had a family who had two sons on a ride at the State Fair of Texas, and the gondola car was thrown off the ride. One son was killed, the other had a skull fracture. We spent a lot of time and money and energy getting that case ready to try.

Even though it was resolved, it effected a change in the safety at the State Fair of Texas. They put in new procedures. For example, in this particular ride, there were a lot of stress fractures in the ride under the plastic cover. What we found out in that case has increased the safety for fair goers.

It helps in trying lawsuits sometimes to get a scouting report the same way football coaches do on other teams.

One of the areas we've enjoyed doing some work in is commercial airplane crashes. We've had a number of them over the years, and ended up trying one in Little Rock. It was an American Airlines crash, where a plane crashed in the middle of a big thunderstorm. They were trying to land and ran off the runway.

When we first started handling commercial airplane crashes, the insurance carrier for the airlines told me they’d like to settle them by seat. If it's a breadwinner, it's a certain price. If it's a housewife, it's a different price. If it's a child, it's another price. If the seat has an older person in it, they said it’s certainly less than a younger person. I said, "Look, I'm sorry, I've had a lot of tort cases over years, but I've never represented a seat. We represent people who are in the seat, and they each have individual cases. You'll either pay the price that we evaluate as the devastation to these people, or we'll try the lawsuit." It was a surprise to them that that's what turned out.

LD: Can you speak to any community or charitable efforts that are particularly meaningful to you?

FB: I've been on the board that governs SMU Dedman School of Law for over two decades. My wife and I've been involved in some of the Scottish Rite fundraising efforts. My wife really gets the credit for our community service work. She's had quite a history. She was on the Parkland Hospital board for a number of years and served a term as chairman. She's been on the State Committee on Rate and Policy Foreign Regulation. She’s been on the Judicial Council. She's been chairman of the Texas Women's Foundation, and has worked with Planned Parenthood and Annie's List. She had two presidential appointments, one with the Federal Aviation Management Committee, and the other with Security Investors Protection Corporation. As a family and a firm, we've been active in a lot of different community events.