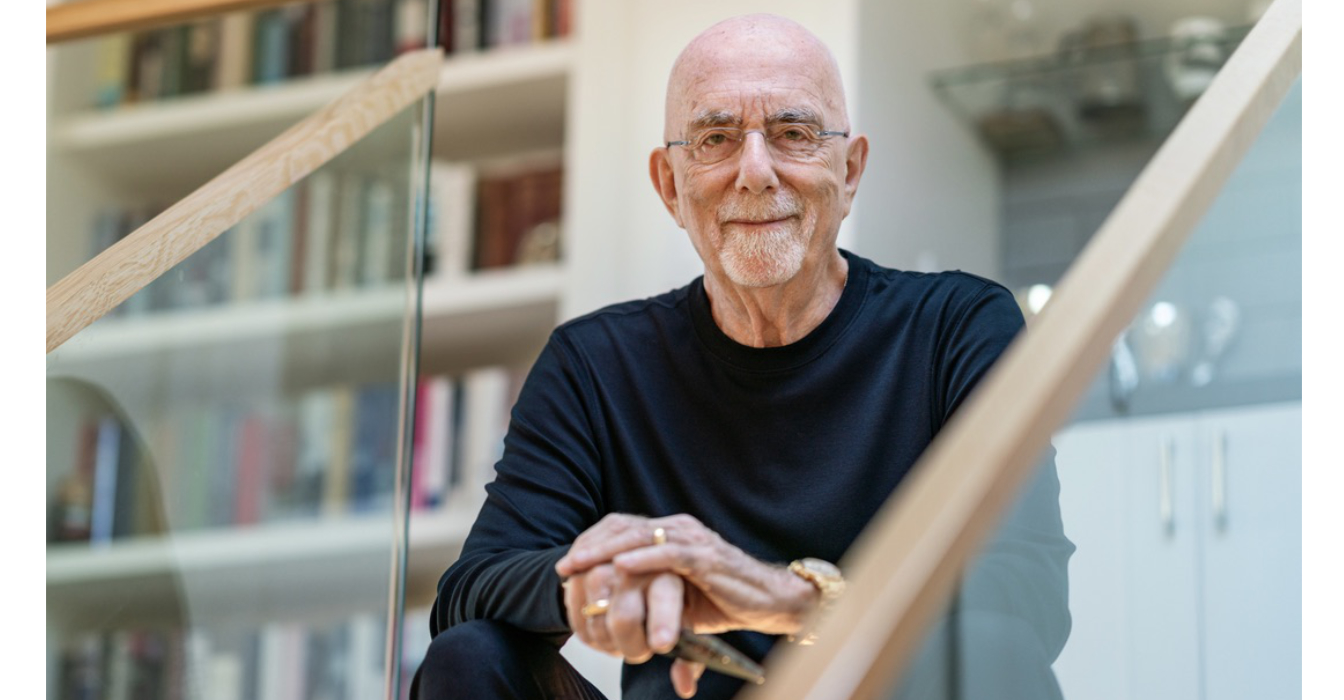

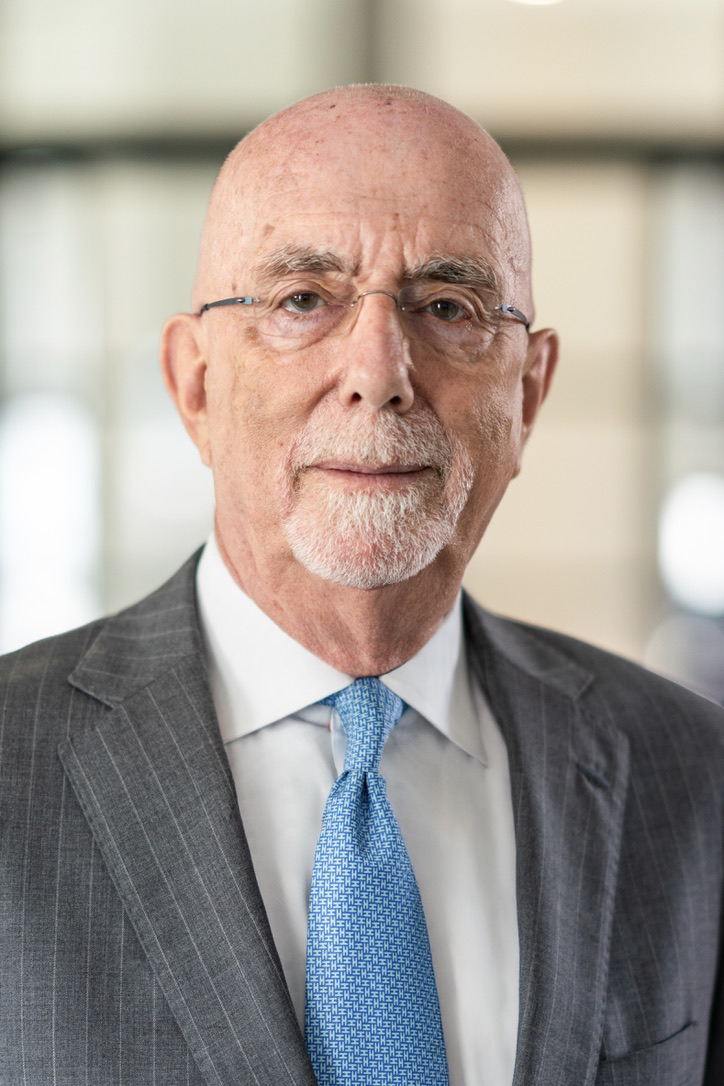

If standout litigator Jonathan Kitchen isn’t in the courtroom, he’s most likely found on the racetrack, flying down the asphalt in a Formula Ford.

A supercharged, competitive environment where cerebral preparation and diligence meet speed and quick thinking, where years of experience and a broad base of knowledge meet precision and power.

The courtroom and the racetrack aren’t so different.

Kitchen grew up in both worlds. A car aficionado since he first began building them with his uncle at age 12 (and even hiding one in the woods abutting his boarding school), Kitchen has been working on cars for decades and racing them with his son for the last 14 years.

At the same time, Kitchen is the grandson, son and nephew of solicitors in England. Kitchen earned his M.A. and PhD from the University of Cambridge, where he was a Fellow of Churchill College, and became a barrister – an English courtroom lawyer. The author of two books, he was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship and moved to the U.S. to teach at Stanford Law School and then began practicing in Big Law – where he began bringing the thrill of the race to the opening statement for a jury.

Over more than four decades as a high-profile practicing lawyer, Kitchen’s cases have only shifted more and more exclusively toward the courtroom. As his experience learning clients, judges and juries inside and out has deepened, Kitchen has built a specialized practice as a “parachuter” – a battle-tested trial lawyer who is unafraid to come into a case at the last minute when experience is needed in the courtroom.

If a typical lawyer is more of a Swiss army knife – helpful across a variety of areas – then Kitchen is a scalpel. Precise, razor-sharp and highly specialized, his expertise is bringing cases to trial. He enters a case with the exactness necessary to execute a successful strategy when a client or referring lawyer is in crisis.

Taking a case to trial is not as frequent an end-result as it used to be, and as a result many lawyers have never actually completed a trial. Kitchen has, again, and again, with the success record to back it up. Contrary to being worried about bringing a case to trial, trial is Kitchen’s lifeblood.

“Trial is the high point of what we do. It's incredibly stressful, but there's a huge amount of satisfaction in doing it,” says Kitchen. “It requires a lot of thought, a lot of chess-like strategy, a lot of preparation.”

Trial is the high point of what we do. It's incredibly stressful, but there's a huge amount of satisfaction in doing it.

In 2020, Kitchen capitalized on that unique practice, starting his own firm, Kitchen Law Group, devoted to both longtime clients and the ability to join any case in the nation when lawyers need help going to trial.

The firm consists of Kitchen and colleagues Sean Fischer and Eric Lode, who have been practicing with Kitchen for years – in Fischer's case going back to his time at the San Francisco office of Baker & McKenzie, where Kitchen began practicing in 1981. There, he took on a wide variety of general litigation for foreign entities, or American entities doing business with foreign companies, mainly in securities law and commercial contract cases. In doing so, Kitchen built substantial relationships with lawyers in high-stakes cases globally – the seeds of the relationships he’d foster traveling around the country to try cases later in his career.

From day one, Kitchen was involved in impactful litigation. In one matter, Kitchen tried a case against the Islamic Republic of Iran in a dispute over the ownership of the airplanes his client used to flee the country. (He not only won, but collected the judgment.) In another case, he represented EMI and Capital Records in a dispute with the Franchise Tax Board in California over whether EMI could be taxed for Capital Records’ sales of Beatles and Pink Floyd albums. Kitchen flew back home to England, where he spent time with “the fifth Beatle” – Beatles producer and arranger George Martin – eventually persuading him to come to San Francisco to testify.

“Ultimately, the threat that somebody as significant as George would actually testify for us along with other people at Capital Records was enough to get that resolved quite well,” Kitchen remembers.

Eventually, Kitchen moved to real estate-focused Cox, Castle & Nicholson. Real estate runs deeply in his family – Kitchen’s wife, Nina Hatvany, has been repeatedly ranked the number one realtor in San Francisco, and their three children (two of whom are also lawyers) have joined the family business. The whole family, then, has a unique insider view into real estate from a variety of angles.

It was at Cox Castle that Kitchen began his long-running representation of real estate giant Taylor Morrison. Kitchen has been litigating cases on behalf of the company – which builds over 12,000 homes nationwide each year – for more than 15 years. That’s since before the company went public – even since before they merged to become Taylor Morrison. In that time, he’s represented the company in California, Florida, Virginia, Texas and Colorado.

Kitchen’s first case on behalf of Taylor Morrison was also the first time that he parachuted into trial at the last minute. He is typically brought in for major litigation – class actions or significant subdivision-wide issues. In one action in Florida, a class asserted that hundreds of houses had been built over unexploded bombs from World War II.

In cases like those, Kitchen builds close partnerships with local lawyers, bringing his trial prowess to their extensive workup of the case – often building years-long friendships. In Texas, Kitchen says, he’s been working with the same Taylor Morrison lawyers for the last 12 years.

The process is not without its challenges though – challenges that Kitchen not only faces, but revels in, diving into what others have started. But that’s the way of the game, Kitchen says.

“You have to be a quick study, you have to be respectful of the choices that other people have made, and you have to bring a second set of eyes to what people have already done,” he explains.

With those eyes, Kitchen brings in his sharpest sets of skills – using evidence, presentation, and experts to put the case in front of a jury in the most effective method possible.

But the true key to his success: psychology.

“Psychology is a huge part – if not the most important part – of working with juries,” Kitchen says. It’s a perspective he’s taken on thanks in part to his wife’s doctorate in psychology, and her thesis on the rehabilitation of discredited witnesses. “I was a very early user of jury consultants and gathering data on how people absorb information – how they learn,” Kitchen explains. In a two-week trial, a jury may have to learn more than they would in two years of college, Kitchen says. So, he focuses on conveying information to a jury in a way that is not only compelling but fits most jurors’ learning styles.

Particularly these days, people think in pictures, Kitchen says. People are far more likely to gather information from their phone screens than from the paper documents lawyers sift through – and they’re used to getting that information rapidly. So, you need to figure out how to get the point to them quickly, Kitchen says.

“The popular image of the trial lawyer is somebody who's asking these devastating cross-examination questions,” he adds. “Of course, that comes up from time to time. But actually, the really significant work is figuring out how to make the arguments sensible and understandable."

The key is to answer the jurors’ most pressing question immediately. That question, he says, is universal: “What is really going on here?”

Jurors want to know why they’ve taken the time to change their schedule and come downtown to be on a jury, he explains. “But, in order to win, in my view, you not only have to be right in the legal sense, but you also have to be right in the sense of communicating what really happened,” he says.

You have to be a quick study, you have to be respectful of the choices that other people have made, and you have to bring a second set of eyes to what people have already done.

That understanding of humanity gets Kitchen off the page and into the jurors’ minds in a way that has yielded crucial results in cases ranging from big to small. Knowing how juries react to given situations is critical. They instinctively do not like cases that they think should not have been brought, no matter how much money is at stake. In one pro bono case, which was a stark contrast from the usual large commercial cases he handles, he represented a young woman who had a nice one-bedroom apartment in San Francisco. She went to stay overnight with her boyfriend, and when she came back in the morning, her apartment had burned down.

“It was devastating. She lost everything,” Kitchen says.

The woman had renters’ insurance, so she was able to replace vital items like her laptop and bed and secure a new apartment. But because the suspicion was that she had unintentionally started the fire by leaving a poster next to the heater, the insurance company sued her for the cost of repairs to the apartment – around $50,000. She had $226 in her checking account.

Kitchen decided to take the case to trial – a move that would shock most lawyers. “The people on the other side called me up and said, ‘What do you mean you're going to trial? I've got a fire report that says your client is responsible,’” he remembers. “I said, ‘Here's the deal. Come to San Francisco and we'll try this case. I'm going to give you two pieces of information: 70 percent of the people who live in San Francisco are renters. And one hundred percent of the people who live in San Francisco hate insurance companies.’”

Kitchen knew the psychology of his jurors. It didn’t matter what the defense had on paper; he knew where the people’s hearts lay.

The company abandoned the case the day before the trial.

“It was a little case, but it stands out because trials are not only about whether you are right as a matter of the documents or the liability, they're about people,” Kitchen says, “You have to have some kind of right on your side in a more profound sense than just the documents.”

Kitchen is widely sought after for his thoughts on the keys to the courtroom – and the ways in which the legal industry is shifting. As the face of trials continue to change, Kitchen says his biggest concern with jurors today is that the chances of getting in front of a jury where they don’t research some aspect of the case themselves, even if they are instructed not to, “is practically zero.”

“If you go out to lunch and you say, ‘Now, what was the name of that thing?’– what’s the first thing you do these days? You pick up your phone and you ask Google, you ask ChatGPT,” he says. “So, even if the judge tells them not to do any private investigation or examine social media and to listen only to the evidence and witnesses as presented, and decide the case based solely on what comes into the courtroom, one of the jurors is still going to look it up before they've finished dinner.”

With that access to potentially one-sided information, Kitchen says, communicating truthfully with the jury is more important than ever; the case a lawyer presents must line up with the story the jurors will learn on their own, and they must portray the truth in a way that gets through.

But Kitchen can’t do it alone. There’s a reason he didn’t hang out his shingle by himself. One of the most important aspects of trial, Kitchen says, is teamwork – and to enable a team to work together, you have to recognize where everyone’s strengths lie, not just your own. He says, “To be good at anything, you have to understand and consistently work at where you can improve, as well as trust and rely on people whose skills you value and appreciate.”

Racing cars, he says, is the same. “There's a lot more to it than just driving a fancy car around the track. You have to put a lot of time into it, a lot of thinking, a lot of preparation with a team behind you. They're not dissimilar.”

After practicing law for the last 45 years, much like racing, Kitchen does not show any signs of slowing down.

“I can't imagine not doing what I do. I don't really have any plans beyond trying to figure out how to do more of it,” he says.

As on the racetrack, he will continue to get ready, suit up, focus in and drive.