[Editor's Note: This article was published on June 18, 2014. In August of 2015, Kathleen Kane was indicted on perjury and conspiracy charges. She resigned on Aug. 16, 2016, a day after a jury found her guilty on nine counts. Read coverage.]

Post-industrial, economically-depressed cities like those in Pennsylvania have seen an influx of low-cost, high-grade heroin. Attorney General Kathleen Kane and her Mobile Street Crimes Unit are trying to prevent their cities from descending into drug-fueled oblivion. If successful, the state’s innovative approach may influence others intent on stemming the root causes of a public health crisis.

Senior Special Agent Marshall "Jess" Freer gathers his crew of narcotics agents in a dingy basement office of Hazleton City Hall and calls them to attention.

"Ok, run it down," says Freer, a ruddy, solidly-built veteran of the Office of Attorney General for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

The dozen or so agents, selected from the Bureau of Narcotics Investigations to form a statewide detail known as the Mobile Street Crimes Unit (MSCU), brief Freer on the day's activities.

With what sounds like a routine array of search warrants and low-level drug busts, the agents roll out in plain cars and SUVs in their jeans, kevlar vests stenciled generically with "POLICE" and guns strapped to their thighs.

Past granite buildings and Victorians of a once-prosperous era given way to decaying tenements and humble storefronts, they head out of town on a road lined with boneyards, quarries and semi-rural homes on cluttered lots.

Dotted with gritty, post-industrial cities such as York, Redding, Scranton, and Wilkes-Barre, this region is a gateway to surrounding states along the North-South and East-West interstates that carry commercial traffic out of Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York City.

And just as these cities receive their meat, produce and consumer goods from trucks traveling along these routes, they receive a steady diet of an increasingly prevalent but undesirable commodity that is poisoning an entire region: Heroin. Cheap, strong Mexican heroin that drug cartels channel through Mexico and into the United States across a porous border that has vexed law enforcers, health providers and the U.S. government for decades.

Freer's unit is the vanguard of an effort to bring resources to local jurisdictions overwhelmed by the drug cartel product, and outmanned by legions of local dealers that make Hazleton a regional hub for well-connected gangs from New York and Philly.

If successful, the MSCU could influence neighboring states intent on beating back the ravages of a drug that governors, the U.S. Attorney General and even the president of the United States have described as the root cause of a public health crisis.

It is not sexy or rewarding work – at least not at first.

The first warrant yields little, so the unit returns to Hazleton in a loosely staggered convoy, setting up on one side of a "half-double," two multi-room houses attached by a common wall and porch.

Elderly residents on the block peer out from behind stained curtains and a stooped old man in a wife-beater, chinos and suspenders ambles out onto the adjoining porch to see what the fuss is about.

The lead agent knocks on the door and then forces it open with a battering ram, as the rest of the unit – including members of the Hazleton Police Department – rushes in from the rear with guns drawn.

Moving from room to room the agents survey the scene, an unoccupied stash house resembling a yard sale, but with air rifles, withering pot plants, foil pipes and chairs jammed up against the doorknobs of the rear and basement doors.

The agents begin the tedious, painstaking work of processing the scene, which contains multiple stashes of Oxycontin that must be gathered up, counted and catalogued by prescription number, prescriber, type and any other identifying marks.

Back in the basement of City Hall a couple of hours later, the smell of stale cigar smoke hovers over the agents as they get to work at their computers and work stations arranged on vintage metal desks.

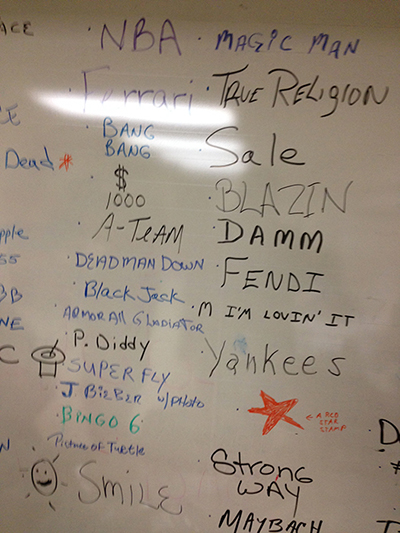

A white board displays two rows of "stamps" for the cheap heroin that will take over the lives of abusers and addicts – after they have virtually bankrupted themselves on prescription pills like the ones the unit just confiscated.

Names like "Foxy," "Maybach," "True Religion" and "Dope Dick."

Once the prescription pill haul is logged in, the information will go to a drug diversion unit that will "run traps" on the prescribing doctors.

Meantime, agents will contact their confidential informants to see if they can locate the doctor or the owner of the house to induce a sale of pills to the C.I. or an undercover agent.

All of the information will be logged into a database that will form the basis of investigations that reach into the pill and inevitable heroin market in Hazleton and its surrounding areas for months to come.

Eventually, when the MSCU moves on to another small city, the information will be left with local police to assist them in their seemingly never-ending battle. Meantime, the unit will share their data with federal law enforcement agencies with an eye toward piecing together money trails that lead into drug cartel ranks.

For now, however, the unit's street-level detail is just beginning.

"A.J., you wanna hit that trailer in Wilkes-Barre?" Freer asks, as they wait for a local judge to sign off on another search warrant. "I can call everyone back, grab a cup of coffee and we can go blow that door in."

"I'd like to," the agent replies.

"I'll be here all night," Freer says, almost as if to himself. "I'm only getting paid for eight hours, but I'll be here all night."

THE PROBLEM AND THE PLAN

Heroin is no longer a big-time inner city drug. According to the Drug Enforcement Administration, in recent years, it has proliferated in wealthy suburbs, poor rural areas and small cities such as Hazleton that have seen better economic times.

Because it is cheaper than prescription opiates that serve as a gateway to addiction, heroin is increasingly popular amongst younger Americans and those who are uneducated, out-of-work or otherwise struggling to make ends meet.

From 2008 to 2013, the amount of heroin seized at the Southwest Border increased from 558 kilograms to 2,111 kilograms per year. Such an increase appears to correspond with increasing levels of Mexican-heroin production and the expansion of traffickers into new U.S. markets, according to the DEA.

At the same time, heroin overdoses increased 45 percent during the last decade, due to an increase in production and the movement of Mexican traffickers into regions such as Northeast Pennsylvania, with its conveniently located trucking routes that connect the surrounding states.

Little surprise then that law enforcement officials in the post-industrial, economically-depressed and increasingly immigrant-populated cities have spotted an increase of low-cost, high-purity heroin available at the street level.

The flood of cheap drugs and resulting drug cash also has led to the proliferation of what the DEA refers to as "trade-based money laundering operations," or, "shadow facilitators," which can be anything from a nail salon to a used-car dealer.

Attorney General Kathleen Kane is in her office in Harrisburg one day last fall, discussing this phenomenon and the genesis of the MSCU, which operates on a $2.5 million budget championed by her and a bipartisan group of state legislators in 2013.

A Democrat in an essentially Red State with a Republican governor and legislature, Kane, in her first year in office, is the first female and first Democrat to serve as Pennsylvania's Attorney General.

The General, as her staff refers to her, is a former street level prosecutor and mother from the Scranton area, and in a short time has become a rising star in Pennsylvania politics. Though she ran for office promising to focus on the job at hand and not her own ambitions, it is tempting to envision her making Republicans - such as Governor Tom Corbett, her predecessor - nervous.

Kane, a 1993 graduate of Temple Law School, is plainspoken and attractive. She speaks with conviction and exudes populist appeal. But it is the audacity to go after entrenched criminal networks that hide behind layers of middle-men, street gangs and cash businesses that could someday mark her legacy.

She describes Pennsylvania – the third-largest state on the Atlantic Seaboard, situated amid major shipping corridors connecting the Northeast, Midwest, South and coastal cities from Maryland to Maine – as a "good place for drug cartels to do business."

"There has to be a better model than getting dealers off the street," she says. "There are billions of dollars of drug money being laundered in this country and we have to try and cut off that money supply.

"What we're doing, it's not your typical task force. And it's not just a community-based approach."

Yet it starts in the community, she says, where state drug investigators can go into harder-hit areas with a saturation patrol that would be impossible for police in cities and townships to muster.

"Our goal is to gather intelligence and trace it beyond the street level," says Kane, noting the importance of also partnering with local police. "We won't stop at the county or the state line."

A key aspect is educating and cultivating residents, Kanel says. "We want them to see how to report a drug deal in their midst and we want to gather more and more information from them. People are begging for it," she adds. "It's actually sad."

For the MSCU's first deployment, Kane says she chose Hazleton based on need, demographics, size and location. With a population of 33,000 and just 38 police officers, the city is big and central enough to a surrounding network of smaller townships to thoroughly test the concept, yet not so large as to become overwhelming, she says.

Last August, as the unit was still getting established in the greater Hazleton area, Police Chief Frank V. DeAndrea Jr. already liked what he was seeing.

DeAndrea is a wiry, intense man with a love of history – and a knack for hyperbole. In his nicely appointed office in Hazleton City Hall, DeAndrea likens Kane and her MSCU concept to General William T. Sherman and his then-modern methods of using raw numbers to outflank the opponent, a break from traditional war strategy that altered the Civil War.

"She's a modern day General Sherman," DeAndrea gushes. "She is changing the way urban drug and drug-crime battles will be fought in the future. She's Mrs. Clean, and she's coming to scrub the place. And when she leaves, she's gonna leave the tools behind for us to protect the community."

According to DeAndrea, Kane deserves credit for "recognizing a problem and coming up with a solution that goes against what everyone else is doing."

He describes with frustration his past dealings with the DEA and FBI, which utilize his local officers as members of a task force that generates proceeds from seizures to fund their future investigations, all while his city is crying out for more help.

"We have 39 gangs and 38 officers," he says. "And the General calls up and says she wants to meet with me about our problem with drugs and violence.

"After we collaborate on this effort, the FBI and DEA call up and say, 'We're already in your town, we don't need another task force.' But we're broke, and overmatched. It's like a high school team going up against an NFL team."

DeAndrea insists that he wasn't "seeing the ball move" with the FBI and DEA - that is, until Kane and her troops came into the picture. "When someone wants to bring in 20 state cops [on a mission-focused unit], why wouldn't I?" he says.

THE PITCH

With 2,500 municipalities in a state with 12.7 million people, Kane realized early on that a lack of coordination between local and federal agencies had created a vacuum for criminal organizations to exploit.

"No one played well together," she says matter-of-factly. "It was like a T-ball game, where everyone jumps on the ball and parents are cheering with delight. Those days are over. We're cultivating an environment that puts ego aside. It's not about credit for a bust. Our resources are thin. We can't go on simply chasing dealers off the street then stop."

A National Geographic Channel segment for the investigative show "Drugs Inc." last year showed Kane on the streets of North Philadelphia, seeing for herself how deeply the heroin epidemic is rooted. Earlier this year she traveled to Arizona and Texas to experience the other end of the supply chain.

"If there's a problem on the border there's a problem in Pennsylvania," Kane says. "You can be anywhere in two hours. There are no local police in some regions and the State Police can only be so proactive.

The cartels have seized on a marketing opportunity east of the Mississippi River based on the economy, lack of coordinated law enforcement and geography.

"The most frightening and shocking fact for me is that dealers used to pay for drugs upfront," she says. "But the drugs are so abundant, and the cartels are so arrogant in believing they are here to stay, that if they lose a load they know there's plenty more."

The traditional role of the DEA, with just 5,000 agents scattered in some 90 offices in 63 countries, is to investigate the biggest and baddest organizations and to cut off that massive supply of dope before it flows into cities and towns like Hazleton.

Kane says she is re-purposing that approach and tailoring it to her state's geography and economy. That means connecting the street level drug busts to the larger supply chain and prosecuting drug dealers and middlemen in between.

"Mass [drug] seizures have been a success, but there's absolutely more going on behind it," she continues. "We can't assume the feds aren't working beyond dope, but in Pennsylvania we aren't interested in a one-pronged approach."

A spokesman for the DEA in Philadelphia says, "We support the efforts of the Attorney General’s Office, however, we cannot comment on how we may integrate law enforcement investigative efforts and resources. We do make every effort to support State, County and local investigations where plausible."

The DEA over the years has deployed "Mobile Enforcement Teams" and similar units to conduct mini-operations aimed at cleaning out particular cities, and it recognizes that something as seemingly insignificant as a traffic stop in Philly could blossom into an international drug-trafficking probe. But, generally, a Washington-based spokesman says, "We don't have the resources to focus on small-time local yokels that produce limited impact. Our resources are limited too. We have to be careful when evaluating a potential investigation to get a bang for the buck."

Kane is on a tight financial leash, which she recognizes, but says the other option was to watch cities like her hometown descend into drug-fueled oblivion. Of her effort to fund the MSCU, Kane concedes it was not easy to go asking for funds. "There were naysayers [in the State Capitol]," she says. "Some didn't believe what we were saying, but when we showed them where drug cartels are known to operate we were able to convince people."

As for skeptics, she says, "You don't want to sign on? Fine. We can proceed without you. The more the merrier. We haven't even sought federal grants yet."

That day could be not too far off. But for the time being, Kane is making her mark in a state with cities that see her as bringing in the cavalry to rescue their drug-infested communities.

Shortly after being elected in 2010, State Senator John T. Yudichak, a Democrat, suspected Hazleton was on the front lines of a major heroin network. A 2011 Department of Justice Report "crystallized" findings that the town was being used by sophisticated criminal organizations as a regional distribution center smack in the middle of the I-80 and I-81 corridors.

Yudichak represents Carbon County and parts of Luzerne County, which have a total of 99 municipalities. He notes that in 2013 just 60 percent of the cities in the area with a population less than 5,000 had a full-time police force. Today just 6 percent do.

"It's perfectly suited for a drug distribution network, with such a limited presence of law enforcement," Yudichak says, noting that it was an easy call to seek involvement from colleagues on both sides of the aisle, with assistance from U.S. Rep. Lou Barletta, a Republican from Pennsylvania's 11th District.

"We wanted to take the 'D' and the 'R' of politics out of it and we needed state and federal assistance," Yudichak says of bipartisan efforts to address the problem. "We needed to break down silos and get the community engaged. People were in a bed of denial."

Yudichak and his colleagues passed an anti-gang law in 2012 and then moved toward creation of the MSCU, which led to a $2.5 million appropriation, "a small investment that has already proved successful as a force multiplier," he says.

"We had to come up with something innovative," Yudichak continues. "We didn't have time to come up with resources for all of these individual cities. So we kicked around a few ideas with General Kane and brought together federal and local partners to create a counter-insurgency unit, with the goal of driving out, disrupting and cutting off drug supplies and dismantling drug operations."

Rep. Barletta, the former mayor of Hazleton who is on the House Homeland Security Committee and the Subcommittee on Border and Maritime Security, says he's been talking about gangs and illegal immigration in the U.S. Capitol since he came to Washington in 2005. But after seeing violence increase dramatically compared to the days when one murder would keep folks talking for seven years, he realized the drug trafficking problem was more than a city could handle.

"For anyone in Congress who has been a mayor, they understand very well how these things are tied to drug cartels," Barletta says. "They know damn well that it's an endless battle, and that if you take a drug dealer off the street there's three more waiting to take his place. It's like drinking water through a firehose."

Of the Hazleton operation and its inevitable conclusion, Barletta says, "The biggest challenge now is to give the local chief of police the resources he needs to keep going, because these cities are cash-strapped. That's where the feds can play a role. I think we can do a better job there.

"The [MSCU] is going to get attention," he predicts. "Cities are crying out for it. And when other states see what is happening they'll want to replicate it."

THE PAYOFF

Six-foot mounds of filthy snow line the pot-hole dotted streets of Hazleton on a mid-February day. Dark clouds promise a steady, freezing rain by dark.

Inside Hazleton City Hall, however, the mood is buoyant, as Sen. Yudichak, General Kane, Chief DeAndrea and the police chiefs of several nearby towns stand before TV cameras to announce the success of the Mobile Street Crimes Unit.

Myriad uniformed local, state and federal law enforcers and officials who participated in the operation pack the gallery above. Mixed in with the uniformed crowd – which includes the members of the National Guard – are the plain-clothed MSCU agents, having just a day before donned their State Attorney General vests for the first time in a climactic sweep in which they kicked in doors, executed warrants and seized alarming amounts of contraband.

To the side of the podium there is a display consisting of the mugs of over 100 arrestees and ominous piles of heroin, cash and guns.

After bunking for five months in local motels away from their families, living on coffee, lack of sleep and carryout from Frankie's Pizzeria, this is the moment these special agents have been working for.

Sen. Yudichak recounts the 2011 Justice Department report that defined the influx of heroin to Northeast Pennsylvania as a "clear and present threat." He attributes the regional spike in homicides and violent crime to gangs and drug trafficking organizations setting up shop in communities that are outmatched by sophisticated criminal organizations.

He recalls a pivotal moment in the origin of the plan, shortly after Kane was elected: "I paid a visit to the Attorney General, and we sat at her kitchen table in her home outside Scranton, and she asked me bluntly, what's the one thing she could do to address the proliferation of violent street crime."

Yudichak then thanks Kane for "listening to the people and staring down the naysayers" in finding the right partners and resources to fight back.

Taking her turn at the podium, Kane harkens her own moment of inspiration: "Three months and four days ago I took an oath of office and swore to uphold the Constitution and the laws of Pennsylvania and the United States, and I also swore I would not forget towns like yours."

Describing herself as a street fighter – "I'm from Westside, that's what we do" – she speaks of how she "begged, borrowed and stole" the money to fund the project as "an investment in the future, in the people of these town and regions."

That investment has already paid off, Kane says, ticking off the names of the gangs the MSCU has disrupted – the Bloods, the Latin Kings, Folk Nation and Dominicans Don't Play, some of which recruit children as young as 9-years-old.

She details the results of the operation: 30 arrests and 9,060 packets of heroin seized in the past three days alone; 35,000 bags of heroin and 120 arrests in all; 97 criminal cases filed in just five months' time; guns, vehicles, cash, and jewelry seized – all in a town of 33,000 which has just 38 police officers.

Even the users and dealers have indicated that the heroin supply has dried up since the MSCU arrived, she says, promising that "we will not have forgotten you, even as we move to another town."

Kane calls for a round of applause for the agents and officers who made it all happen, then looks up into the gallery, smiles and says, "Alright, you've had your applause, now get back to work."

Stepping to the microphone, Chief DeAndrea holds forth with a flurry of references ranging from the Liberty Bell to the Battle of Iwo Jima to the sea battles of John Paul Jones.

"We are dividers of good and evil," he says, invoking the memory of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a fellow student of the Greek philosopher-poet Aeschylus, who wrote about hope, empowerment and faith restored.

In a different time and place such lofty rhetoric might ring hollow. Not here, though, not now. This is DeAndrea's moment of relief and gratitude. He thanks Jess Freer and his unit for "adopting [Hazleton] as your own," for making it a better place. "You've made this a personal mission," he says.

Turning to Kane, the chief says, "Now I know why Justice is always depicted as a woman." The compliment draws fond laughter from the gallery. "You have accomplished more in six months than most accomplish in a lifetime," he says. "I call this Operation Rising Star, because we now have a light to follow. You are my rising star, and it's an honor to stand in your light."

DeAndrea is on a roll. He thanks the officials and agents in his midst, visibly struggling to contain his emotion. But he does.

As the event wraps up, law enforcers of all stripes – FBI, DEA, State Attorney General, cities of Hazleton and West Hazleton – disperse in all directions with an air of purpose and intent.

Kane talks with local TV reporters, the National Geographic crew and a reporter from Washington, D.C., who has seen the restoration of hope in a city that just five months ago was on the brink of despair. She will be attending community events throughout the rest of the day – an effort to connect with everyday people more suited to a political candidate than a recently elected law enforcer.

Freer and his crew descend back to their cluttered war room in the bowels of City Hall to process evidence, update their database, and prepare to deploy to the next town.

About the author: Jeffrey Anderson is a veteran feature writer and award-winning investigative reporter from Washington, D.C. He previously has worked at the Los Angeles Daily Journal, L.A. Weekly, Baltimore City Paper and The Washington Times. He can be reached at byjeffreyanderson@gmail.com.