Inside Guantanamo: The Military Commission Against Abd al Hadi al Iraqi

By John Ryan | October 1, 2015 | Guantanamo Bay, News & Features

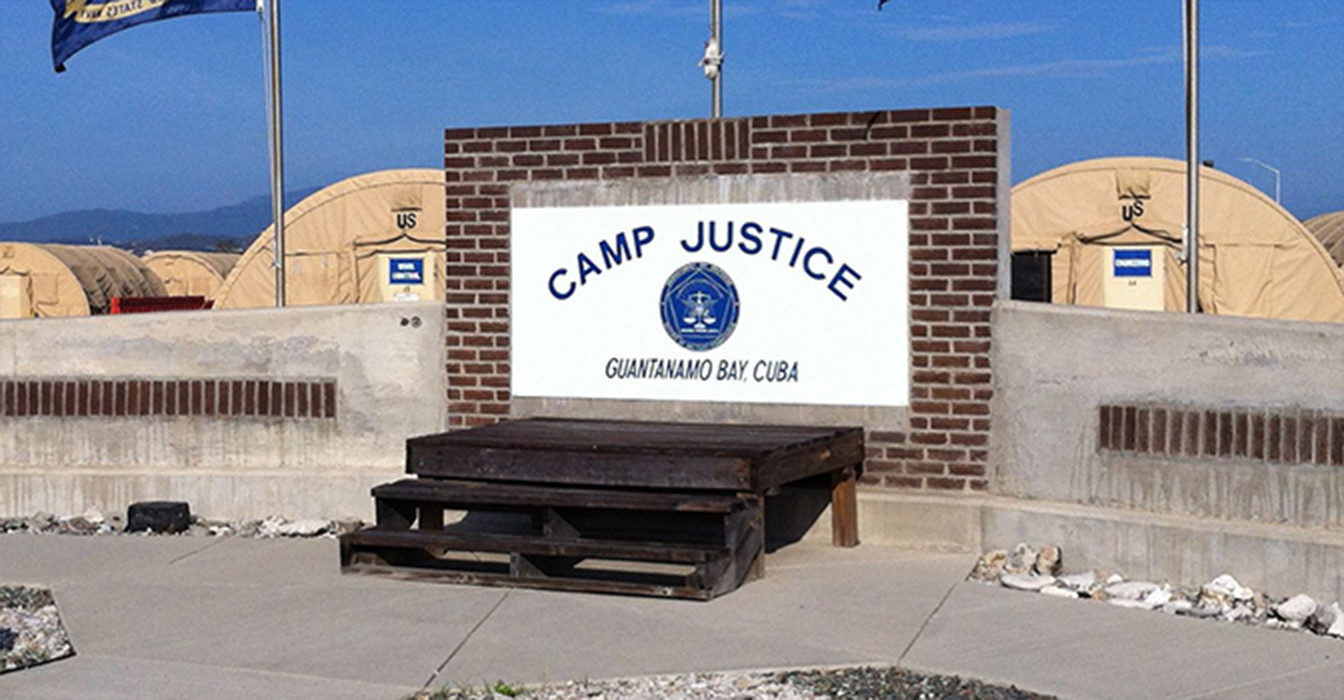

Photo: Camp Justice houses the legal complex on Guantanamo Bay where detainees are to be tried.

Watching proceedings in Courtroom II of the Expeditionary Legal Complex on Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where high-value detainees held on the U.S. Naval base are to be tried through military commissions, is not your typical court experience. The spectators gallery is separated from the court by soundproofed glass with an audio and closed-circuit video feed on a 40-second delay, which allows the judge to block classified information from reaching the public. On a recent tour of the facility for media and NGO representatives, a court official joked that watching live proceedings with the delayed audio was like sitting through a poorly dubbed foreign film.

It remains unclear when these and other high-tech features of the complex will be used for actual trials. At a Sept. 22 hearing in the case against Abd al Hadi al Iraqi, an alleged senior al Qaeda operative accused of war crimes, a judge granted Hadi’s request to have his two defense lawyers removed from the case – creating a delay of indeterminate length. Hadi’s case has a lower profile than the two other active cases at Guantanamo: one against the five defendants charged with key roles in the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, the other against the alleged planner of the USS Cole bombing in 2000.

Both of those cases are also stalled in pre-trial legal proceedings without trial dates in sight.

The reason for the dismissal of Hadi's attorneys was not discussed in open court. Judge J.K. Waits, a Navy Captain, said he did not find “good cause” – such as a conflict or breakdown in attorney-client communications – but that he was “basically giving Hadi a free pass,” allowing him “to fire his counsel one time.” Earlier in the case, two of Hadi’s defense lawyers were removed against the defendant’s wishes, which Waits said played a role in his flexibility this time.

Still, the judge told Hadi that he didn’t want the issue to be used as a way to affect the proceedings. The warning struck a nerve with Hadi, who said that “all the delays that happened in the past wasn’t because of me.”

“I stayed here in Guantanamo for seven years and six months without trial, and then after that, my case was sent to court,” Hadi, speaking in Arabic, said in response to Waits asking him if he understood his rights to counsel. “It took a long time.”

So did Hadi’s attempts to voice his complaints, as he and the voice of a female translator – who is not in the courtroom, a measure to protect the safety of the translators – were soon speaking over one another. (A translator also sits in open court at the defense table to further assist with communications.) A frustrated Waits reminded Hadi to “speak in snippets.”

Hadi is being tried under the Military Commissions Act of 2009, which replaced legislation establishing military trials during the Bush administration. President Obama initially halted military commissions shortly after taking office in 2009. However, within months he was touting the planned due-process reforms of the commissions – including prohibitions on using coerced testimony – and signed the MCA into law in October 2009. Obama ordered the resumption of military trials in Guantanamo in March 2011. Congress has blocked the transfer of detainees to U.S. soil, removing for now the option of federal court trials.

Hadi was captured in 2006 and held in CIA custody until his transfer to Guantanamo in 2007; he was arraigned in his military commissions case in 2014. He faces numerous charges for his alleged role as the leader of al Qaeda operations in Afghanistan and Pakistan, between 2002 and 2004, that targeted U.S. soldiers, coalition forces and civilians. Hadi, an Iraqi who is believed to be in his 50s, also allegedly played a key role in al Qaeda’s insurgency in Iraq in 2005 and 2006.

Under court rules, he is automatically given a military lawyer but not a civilian lawyer, which is required only when the death penalty is on the table – as in the 9/11 and USS Cole cases. Hadi is facing a life sentence. His present team, Marine Lt. Col. Thomas Jasper and Air Force Maj. Robert Stirk, will continue to represent him in a limited capacity until his new lawyer – identified as Army Maj. Robert Kincaid – can take over the case. Kincaid needs to receive his security clearance first. The timing of that was uncertain, as were the chances Hadi would want to work with him.

“Once I meet him, I will present my opinion,” Hadi told the judge.

Hadi also wants a civilian lawyer and seems likely to get one. Under the rules, he can either pay for one, find pro bono assistance, or the chief defense counsel for the commissions can use government money to hire one. Brig. Gen. John Baker, a Marine newly installed in the top defense post, told reporters in a brief post-hearing meeting that he intended to use his authority to find a civilian lawyer for Hadi.

Waits’ decision halted the case as it approached oral arguments on some important legal issues. Hadi’s military lawyers were seeking to suppress statements their client made to FBI agents at Guantanamo between May 2007 and January 2009, contending that the interrogations took place after Hadi asked for and was denied legal counsel. In their brief, Jasper and Stirk argued that Miranda guidelines and the 5th Amendment protections against self-incrimination should apply to commission trials, though they acknowledged that the MCA was “silent” on the issue. The MCA requires judges to take into account “the totality of circumstances” when deciding if a statement is voluntary.

In the government’s response, Army Lt. Col. David Long argued that Hadi’s statements – in which he “made substantial admissions” – easily met this standard, and that Congress never intended Miranda to apply to the commissions. Long contended that the defense was confusing domestic arrest and custody – a typical Miranda situation – with Hadi’s capture under the Authorized Used of Military Force in the war against al Qaeda. The FBI told Hadi he was not entitled to a lawyer because he didn’t face charges at the time, yet he continued the interviews voluntarily, Long said in his brief. (He added that the “stringent” due-process protections contained in the MCA should prevent Waits from even getting to the issue of whether the 5th Amendment applies.)

The chief prosecutor of the military commissions, Army Brig. Gen. Mark Martins, declined to comment on the Miranda issue as it related to Hadi’s case during a pre-hearing meeting with reporters at Joint Base Andrews, in Maryland, on Sept. 20, the day before the flight to Guantanamo. The government has prevailed on this issue before: In the USS Cole case against Abd al Rahim al Nashiri, the judge rejected similar Miranda arguments by his lawyers in a November 2014 decision.

Martins did briefly discuss the other procedural step looming in the Hadi case – the government’s burden to establish the jurisdiction of the military commissions by presenting evidence that Hadi was an “alien unprivileged enemy belligerent” in his alleged role in al Qaeda. Martins said that the process speaks to the “narrowness” of the commissions, in terms of when and how they should be used.

“You can’t use wartime authorities any old time,” Martins said of the threshold issue. “You gotta get across the 50-yard line, if you will.”

Before arguments on the jurisdictional issue, lawyers from both sides and the judge would need to hold closed hearings to discuss the potential evidence involved, to identify what may be classified and unsuitable for open court. Progress on this front was theoretically possible last week, but these will now be a matter for Hadi’s new team.

The one-hour hearing seemed especially brief given the effort involved in holding it. The Department of Defense charters a flight out of Joint Base Andrews for lawyers and staff working on the case, as well as for family members of the victims (none attended this hearing), media and NGO observers. Lawyers working on other commissions cases and habeas proceedings for detainees also join these flights. (Judge Waits has to start his trip from his base in Naples, Italy.) A 20-minute ferry ride then takes the group from the airstrip to Camp Justice, the part of the base that houses the court complex. The hearings are also viewable on a closed-circuit feed at Fort Meade in Maryland and Fort Devens in Massachusetts.

For hearings at the Expeditionary Legal Complex, the detainees are brought from their detention facility elsewhere on the base to small holding cells a short walk outside Courtroom II. An empty cell opened up for last week’s tour had a TV monitor – which allows a defendant to watch hearings remotely – and an arrow on the floor pointing towards Mecca.

An adjacent storage unit contained a B.O.S.S. – a body orifice security scanner – that allows security personnel to detect metallic objects in detainees when they sit or stand behind the device, which is less invasive than strip searches. On the walkway to the courtroom – surrounded by covered chained-link fencing – visitors passed several chairs with security straps that are used for unruly detainees who must be in court. No photography is allowed anywhere within the court complex, and photographs cannot be taken of the outside fencing.

On the day of his 10 a.m. hearing, Hadi was sitting calmly at the defendant’s table by the time observers filed into the spectators gallery. He appeared somewhat off in the distance – separated by the glass as well as several tables, as the court is designed to try up to six defendants at once.

At 10:10 a.m., lawyers from both sides filed out of the front of the court and did not return until 10:45 a.m. Hadi, in white clothing and turban, spent the time chatting with the male translator at his defense table, occasionally smiling and laughing and regularly stroking his dark gray beard.

After arriving in court, Waits began the hearing by summarizing a handful of recent “Rule 802” conferences – private meetings between the lawyers and the judge – since the last scheduled hearing in the case in July. These involved the representational issues surrounding Hadi and culminated in Waits’ decision to remove the defense lawyers from his case.

One of his lawyers, Jasper, stood up to say that, in fact, it’s the “authority and sole discretion” of the chief defense counsel to excuse defense lawyers from the case. Waits said he did not want to have that particular “food fight” at the moment but nevertheless characterized Jasper’s position as “absurd.”

Hadi remained calm but for an apparent surge of adrenaline during his complaints about the length of time to get his case going. Hadi added that his “meetings with defense lawyers were spied on,” though he did not specify how or when.

After the hearing, a commissions spokesperson pointed out that Hadi has not filed any spying allegation before the commission, though he is allowed to.

"Although I will not comment on specific cases or on claims that have not been raised, when these types of allegations have been raised in the past, I have stated unequivocally that the prosecution has never listened to a single attorney-client communication,” Martins added in a statement. “And in those contexts I have also done my due diligence to ensure that no entity of the U.S. government is listening to, monitoring, or recording attorney-client communications at the detention facility in Guantanamo Bay."

The spying issue has hovered over the commissions since defense lawyers in the 9/11 case discovered that a smoke alarm in an attorney-detainee meeting room was actually a listening device. The matter received a good amount of media attention, including from "60 Minutes" in a Nov. 2013 segment on the commissions.

Courtroom II was built specifically for the 9/11 case. Former Attorney General Eric Holder had intended to try the case in Manhattan federal court but the plan caved under political pressure. Accused 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and four co-defendants were arraigned in a new commissions case in May 2012.

Hearings in that case are scheduled for the last two weeks of October. However, no one who traveled for the Hadi hearing seemed willing to bet the 9/11 case would move forward as planned. The case has been stalled for several months thanks to last year’s revelation that the FBI had been investigating certain members of the defense teams. The investigation created potential conflict-of-interest issues between attorneys and their clients that the judge on the case – Army Col. James Pohl – has yet to fully sort through.

The day of Hadi’s hearing became more eventful as it went on. In the afternoon, the Department of Defense announced that it had transferred one of the Guantanamo Bay detainees, Abdul Shalabi, to Saudi Arabia. The Periodic Review Board established by President Obama in 2011 to review the detention status of detainees concluded that his detention was no longer necessary, reducing the number of detainees at Guantanamo Bay to 114.