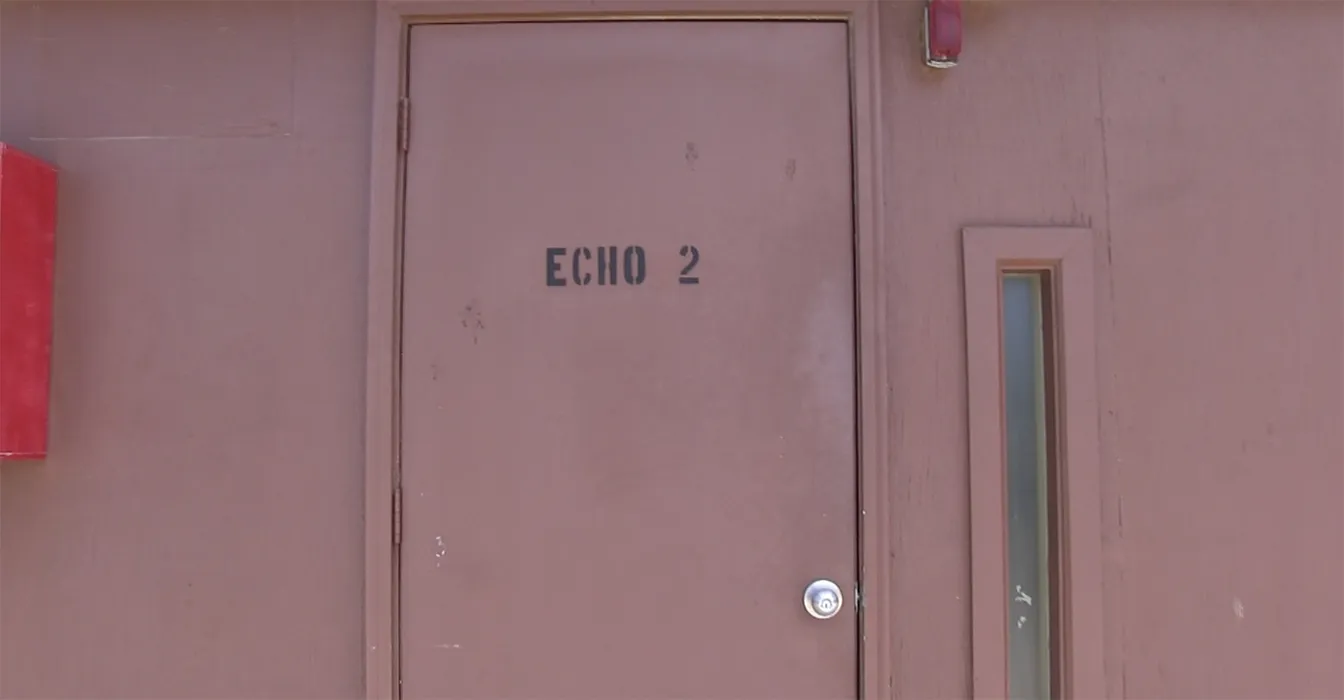

A location inside the Guantanamo Bay detention facility. A Joint Task Force Guantanamo public affairs unit approved this photo taken during an August 2016 media tour.

Guantanamo Naval Base, Cuba –The tireless pursuit for justice for the Sept. 11 attacks was underscored by the testimony this week of FBI Special Agent James Fitzgerald, who has spent the majority of his 23-plus years at the bureau working on the investigation. He logged five straight days of testimony on what has become the core dispute in the pretrial hearings in the prosecution of five men accused of plotting 9/11: whether the FBI's involvement in the CIA's black-site interrogations should disallow statements provided later, in 2007, in interrogations by the FBI.

Under direct examination by the prosecution, Fitzgerald portrayed his four-day interrogation of defendant Ammar al Baluchi at Guantanamo Bay in January 2007 as voluntary and largely disconnected from the CIA, whose personnel had interrogated and abused the defendants at black sites in the years before.

Fitzgerald testified that he started the interrogation as instructed by his FBI superiors: telling al Baluchi that he wouldn't be returned to the CIA, and inquiring if he would voluntarily answer questions. Al Baluchi did so, confirming details of wire transfers of money and other assistance he allegedly provided to the hijackers, according to Fitzgerald’s testimony. The government has previously acknowledged that the January 2007 statements are among the most critical evidence for its case against the defendants.

“I would describe it as courteous, professional, respectful rapport,” Fitzgerald told prosecutor Jeffrey Groharing on Monday.

He also testified that the CIA did not prepare him “at all” for what Fitzgerald described as a “re-interview” of the detainee, who is the nephew of accused plot mastermind and co-defendant Khalid Shaikh Mohammad.

Under cross-examination by James Connell, al Baluchi’s lead lawyer, Fitzgerald confirmed that he and his colleagues sent hundreds of interrogation questions to the CIA while the defendants were at the black sites, and that the CIA had sent cables back with significant amounts of information that is now relevant to the case.

As he neared the end of his cross-examination Thursday, Connell asked Fitzgerald whether, in fact, he had testified against al Baluchi on any topic that was not covered at some point by CIA cables from the black sites.

“I don’t know, precisely,” Fitzgerald responded.

What was less clear after a week that was both mind-numbing in detail and riveting in broad narrative was the extent to which the FBI benefited from the information elicited in the abusive CIA interrogations when orchestrating its own interrogations in 2007. Connell wants the judge, Air Force Col. Shane Cohen, to suppress any statements made during the 2007 interrogations. He claims that the level of CIA-FBI coordination during interrogations should disallow the 2007 statements as obtained by torture – even though Fitzgerald and other FBI agents did not employ any abusive techniques themselves at Guantanamo.

Fitzgerald testified that he did not recall reading much in the CIA cables and said he did not use them to structure his questioning of al Baluchi, which was based more around financial documents and photos of the hijackers. At the same time, he acknowledged that he accessed the secured CIA system that contained the black site statements prior to starting the January 2007 interrogations.

In his most dramatic exchange with Connell, Fitzgerald acknowledged that – when he was sending questions to be asked of the detainees at the black sites – he might have had some knowledge of the abusive nature of the CIA interrogation program.

“Perhaps I did,” Fitzgerald said. “I knew it was very different from a law enforcement approach.”

“Why were you willing to participate in something like that?” Connell asked.

“There were 3,000 dead people and there were a multitude of threats,” Fitzgerald responded.

His actions were “reasonable,” he testified.

The testimony by Fitzgerald, who currently heads a surveillance unit in the Boston office, consumed almost the entire second week of the three-week hearing underway at Guantanamo. In oral arguments during the first week, Connell said that the government had declassified the fact that the FBI had detailed agents to the CIA’s interrogation program and that a location on Guantanamo Bay had previously been a CIA black site. (His client did not spend time at the location when it was a black site between 2003 and 2004, he said.)

Cohen has focused the current hearing on Connell’s suppression motion as well as his challenge to the military commission’s “personal jurisdiction” over al Baluchi. Once a defendant has filed this jurisdictional challenge, the prosecution team must provide some evidence showing a nexus between the defendant and the alleged crimes – creating something of a mini-trial. Groharing’s painstaking direct examination of Fitzgerald on Monday and Tuesday was meant to lay foundation of the government's case connecting al Baluchi to the attacks to establish jurisdiction, in addition to countering Connell's arguments for suppression.

The complexity and length of Fitzgerald’s testimony highlighted the vast amount of work before Cohen, given that it's expected he also will have to hold suppression hearings for the other four defendants. (Three defense teams also have not yet filed their personal jurisdiction challenges; the government prevailed against the first jurisdictional challenge filed by Mustafa al Hawsawi.) The judge has set a trial date for January 2021 but has repeatedly stated that he is willing to change that date based on progress in upcoming months.

Witness testimony for the motion to suppress al Baluchi's statements is expected to stretch over at least the next two sessions; those two-week sessions are scheduled to start in late October and late January. On Thursday, Connell estimated that testimony from James Mitchell – the CIA contractor who developed the black site interrogation program – could itself take two weeks. It is not yet clear when other defense teams will be ready to start questioning witnesses with overlapping relevance.

Cohen, who is relatively new to the post, is also assessing whether these hearings are fair in light of investigative restrictions the government has imposed on defense teams. Throughout his testimony, Fitzgerald repeatedly said he could not provide information on the identities of CIA personnel, foreign entities that provided assistance to the U.S. or the precise origins of certain types of evidence. The government has asserted a national security privilege on those topics.

While Connell largely knew that Fitzgerald would be unable to respond to those lines of inquiry, he started the exchange to establish a record for Cohen and any appellate review. Connell occasionally stepped away from the podium to huddle with Groharing and another of the prosecutors, Clay Trivett, to determine the exact limits of what he could elicit.

While the awkward process made for more difficult viewing, Cohen told the courtroom on Thursday that he was pleased with it.

“The professionalism that was exhibited by these three gentlemen should be commended,” Cohen said.

Groharing conducted redirect examination of Fitzgerald on Friday, seeking to counter any notion that the agent may have relied on CIA black site statements for his interrogations of al Baluchi at Guantanamo Bay in 2007. Groharing inquired if Fitzgerald recalled using any statements from the black sites.

“I do not have any recollection of any statement,” Fitzgerald testified.

Connell then called former FBI Special Agent Abigail Perkins as a witness. Perkins, who is now a contractor for the Department of Energy, took notes during the al Baluchi interrogations that Fitzgerald led at Guantanamo Bay; she herself played a lead role in the interrogations of other detainees, including co-defendant al Hawsawi.

Perkins recounted with greater clarity than Fitzgerald going to a location in Virginia to access the classified CIA network that contained the information from the black sites. She said she spent a few months working at the facility before going to Guantanamo Bay in January 2007 to begin the interrogations, and that Fitzgerald was also at the Virginia facility. However, Perkins said she spent her time reviewing the materials on the three detainees for whom she was the lead interrogator.

Under questioning by Groharing, Perkins testified that she had no doubt that al Baluchi participated voluntarily in the Guantanamo interrogations. He was not confused, anxious or nervous, she testified.

“He seemed very relaxed,” Perkins said.

Additional witnesses for the suppression and jurisdictional disputes are scheduled for next week.

About the author: John Ryan (john@lawdragon.com) is a co-founder and the Editor-in-Chief of Lawdragon Inc., where he oversees all web and magazine content and provides regular coverage of the military commissions at Guantanamo Bay. When he’s not at GTMO, John is based in Brooklyn. He has covered complex legal issues for 20 years and has won multiple awards for his journalism, including a New York Press Club Award in Journalism for his coverage of the Sept. 11 case. View our staff page.