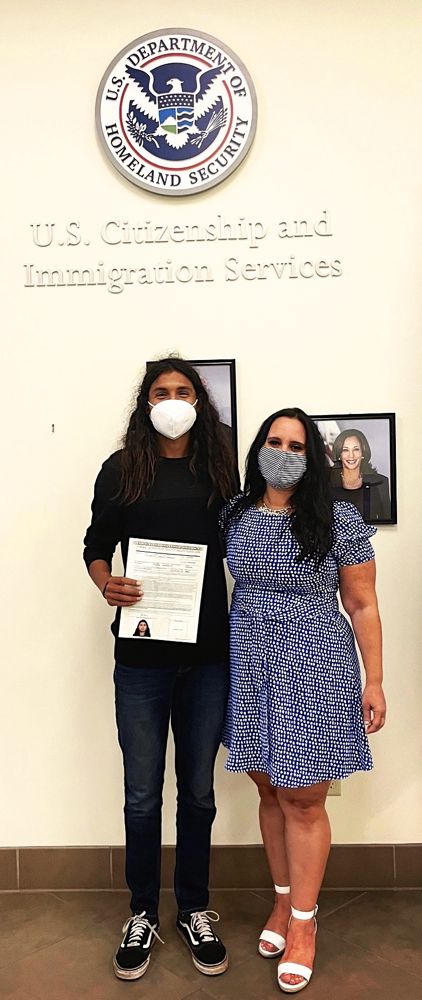

Growing up in America afforded Luis Grijalva the opportunity to become an Olympic-level runner.

But because of circumstances outside of his control – namely, those surrounding his arrival in the U.S. when he was only a year old – the 22-year-old nearly missed his chance to compete in the Tokyo Games.

The Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program that granted him temporary protection from deportation and allowed him to pursue a college education requires “advanced parole” to travel outside the U.S. and return, a process that typically takes three to five months.

Grijalva, who qualified for the Olympics only weeks before the 5,000-meter track-and-field event, was barely able to obtain his approval for the trip in time. And future athletes may not be able to do so at all, no matter how bright or promising their opportunities.

In mid-July, a federal judge in Houston shut down any further grants of protected status through DACA, a program created in 2012 after multiple failed attempts to shepherd a relief bill for immigrants like Grijalva through Congress.

“This was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” said Jessica Smith Bobadilla, Grijalva’s Fresno, Calif., based lawyer. Given Americans’ passion for sporting events, she hopes the publicity surrounding the case will push U.S. citizens who might not typically concern themselves with immigration issues to “push their senators and representatives to find a long-term solution for DACA.”

Controversial since its inception in 2012, the program previously survived multiple attacks from Republican lawmakers, persevering through even the existential threat posed by former President Donald Trump, who campaigned on a promise to wall off the southern U.S. border, and a Supreme Court challenge.

Now, DACA is in a state of limbo.

U.S. District Judge Andrew Hanen - an appointee of the second President Bush to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas - effectively blocked the Biden administration from helping childhood arrivals whose applications hadn’t yet been approved under DACA. However, he allowed immigrants who previously had received temporary protected status to retain it and obtain renewals, which are required every two years.

'Splitting the Baby'

“Hundreds of thousands of individual DACA recipients, along with their employers, states and loved ones, have come to rely on the DACA program,” Hanen wrote, staying his cancellation of that part of the program for the present. “It is not equitable for a government program that has engendered such significant reliance to terminate suddenly,” he continued, while explicitly reserving the option of shutting it down in the future.

In legal slang, the ruling amounts to “splitting the baby,” a reference to Solomon, the Biblical monarch renowned for his wisdom who once resolved a dispute about the parentage of a child by decreeing that it should be divided between the two women claiming to be the boy’s mother.

When Solomon called for a sword to carry out his judgment on the spot, the real mother agreed to give up the child to her rival rather than see him slain. The king awarded her custody.

Hanen’s ruling, while unlikely to achieve a similarly dramatic delivery of perfect justice, still avoided the more draconian options available, immigrant advocates say.

It allows at least some time for the Biden administration to pursue Congressional relief and court appeals without abruptly stripping DACA recipients of the lives they’ve been able to build by pursuing higher education and legally-recognized employment.

While both options are time-consuming and face at best uncertain odds, given the conservative majority on the U.S. Supreme Court and razor-thin Democratic control of the Senate, they are the only viable tools left.

President Biden has promised that the Justice Department would appeal the ruling and, in a statement shortly after it was handed down, again urged Congress to pass the American Dream and Promise Act, approved by the House of Representatives in March.

Only the legislative branch, he said, “can ensure a permanent solution by granting a path to citizenship for Dreamers that will provide the certainty and stability that these young people need and deserve,” he said.

Living in Fear

The bill - which would direct the Department of Homeland Security to create a streamlined system for DACA recipients to apply for lawful permanent residency, commonly referred to as having a green card – could likely be passed only as part of a budget reconciliation measure.

The method, limited to bills with an economic impact, requires only a majority vote in the Senate rather than 60-vote filibuster-proof backing, the latter of which is a near impossibility with the GOP controlling half the chamber.

“It is my fervent hope,” the president said, that “Congress will finally provide security to all Dreamers, who have lived too long in fear.”

While today’s environment is less threatening than it might have been under a second Trump administration - with Immigrations and Custom Enforcement now directed to prioritize scrutiny of recently-arrived undocumented immigrants and those who might pose national security or public safety threats rather than someone whose DACA status is in flux – even people already shielded by the program are wondering when it might disintegrate.

According to the latest statistics from the Congressional Research Service, which provides data and analysis to lawmakers, there are now 636,000 people who have met the criteria - arriving in the U.S. before age 16; being in school, having graduated from high school or the equivalent or having been honorably discharged from the armed forces; and having not been convicted of a felony or significant misdemeanors.

Some 1.3 million additional immigrants meet all the DACA requirements, including being at least 15 years old, but haven’t yet applied, according to estimates from the nonpartisan Migrant Policy Institute.

They - along with others who may become eligible after completing educational requirements, for example - are faced with a Catch-22 dilemma: Apply now, in order to be included in any future cut-off that a court or Congress might set, or refrain in case the detailed data required for approval create a greater risk of enforcement and deportation later without yielding any benefit.

Many applicants are desperate “to get documents, to get status, to be able to have a work permit, a Social Security card and to actually lawfully work, to live their lives aboveboard, be able to file taxes, be able to enroll in college,” said Jodi Zeisemer, director of the immigrant protection unit at New York Legal Assistance Group.

The organization, founded in 1990, originally focused on refugees from the former Soviet Union and has since expanded to work with a variety of immigrants, mostly in the New York City area.

Along with citizenship and green card applications, the group handles a number of DACA cases, Zeisemer said.

In addition to the personal identification information DACA applicants must provide – which includes all current and previous addresses as well as fingerprints and photographs that can enable facial recognition technology - they are responsible for a $495 fee and sometimes must pay for additional legal assistance.

No Age is Too Young

Clients who were preparing to file applications but hadn’t yet done so have begun reaching out to the Legal Assistance Group to question whether it’s still worthwhile to complete them, Zeisemer added.

“Submitting an application and paying a fee exposes them to risk,” she said. “They’re providing a lot of information to the government, so they may not want to do that.”

Further complicating the choice is that many of the potential applicants making it are only 15 years old, she said.

“It’s horrible that we force this on kids, but that’s the nature of immigration law,” Zeisemer explained. “We don’t make any distinctions: There’s no age that is too young to deport. We deport babies, teenagers, toddlers and we make them go through an individualized process. This is not the most egregious example, but this is an example of having these very weighty decisions that have to be made by people who are mentally and developmentally not really prepared to make them.”

Some of the concerns the teens are wrestling with are the same ones that kept previously eligible immigrants from seeking DACA protection in the first place, said Lenni Benson, who teaches constitutional and immigration law at New York Law School.

“I have done a lot of free clinics where I have met members of the public and I’ll go through their cases and I’ll say, ‘You’re eligible to apply; do you want to apply?’” she said. “And they’ll give me reasons why they don’t.”

One is that the program was never confidential, and particularly during the Trump administration, there was concern that the data applicants supplied might endanger themselves, or more likely, their families.

Another reason people offered, she said, was that DACA “doesn’t really give me anything. I’m self-employed, I run a business, I don’t need to work for an employer and I’m managing OK. Why would I go for this temporary program that doesn’t really give me anything? If I did end up in deportation proceedings, I could just apply then. Why bring myself to the attention of the government?”

'All I Know is the U.S.'

Indeed, the benefits of DACA have always been transient. Even when approved, it lasts for only 24 months and requires constant renewal. At present, there’s no path to either a green card or full citizenship for recipients, who must negotiate a morass of red tape just to travel outside the country temporarily, as Grijalva discovered.

“All my life, all I have known is the United States,” he wrote in an Instagram post in July. “Even though my roots started in Guatemala, I feel as American as anybody else who was born here.”

The U.S., at least officially, takes a different view: DACA, despite its benefits, denies him the freedom to leave the country and return, an ability athletes born here might take for granted.

Competing in Tokyo offered not only the honor of representing Grijalva’s home country of Guatemala but of becoming a voice for “over 600,000 Dreamers like me,” he wrote.

Grijalva is likely to face similar dilemmas in the future if he continues racing, said Bobadilla, his attorney.

“This young man almost missed his chance to get on his flight in time to compete,” she explained. “Not everything we do in life has a three- to five-month window where we know it’s going to happen, especially in competitive situations, whether they’re academic or sports or other things. This illustrated how that can lead to a really horrible result.”

Ideally, Congress will solve the dilemma by creating a path to citizenship or permanent residency for DACA recipients, she said. In the interim, solutions might include short-term approval for specified types of travel or an expedited approval process for advanced parole, perhaps requiring an additional fee.

Regardless, young athletes who qualify for the Olympics shouldn’t have to go through what Grijalva did, she added: “There will be more situations like this that come up.”