With everything that’s happened in the world since Sept. 11, 2001, it’s understandable that many Americans remain unaware of one staggering fact: The alleged planners of the attacks have yet to be tried. In “America’s Trial: Torture and the 9/11 Case on Guantanamo Bay,” Lawdragon editor John Ryan pulls back the curtain on the case that was once expected to be “The Trial of the Century” but has instead been stuck in a never-ending grind of pretrial proceedings.

Drawing on ten years of firsthand reporting, Ryan documents the military commission against the five Guantanamo detainees accused of orchestrating the worst terrorist attack in U.S. history. The case has been plagued by delays, legal entanglements and the shadow of CIA torture – raising difficult questions about whether a democracy can fairly prosecute men it once subjected to severe abuse and incommunicado detention. Despite the case’s historic weight, it remains an under-reported and, at times, ignored case.

Ryan, one of only two journalists in the world to report regularly from the base over the past decade, has attended every session since October 2015. Weaving in elements of journalistic memoir, “America’s Trial” offers a rare glimpse into the surreal, high-stakes and often absurd world of Guantanamo’s legal ecosystem – where a small beach town becomes the unlikely stage for a reckoning with national trauma and moral compromise.

Lawdragon: Congratulations on the launch of the book! How did you first decide to write about the 9/11 case and its consequences?

John Ryan: Thank you. I started traveling to Gitmo in September 2015, and my first attendance of a 9/11 hearing was the next month. I went to get some color for a profile I was writing about David Nevin. As I explain in the book, he was the lead lawyer for Khalid Shaikh Mohammad. But when I got there, there were so few journalists covering the case I thought it made sense to also write some stories about what was happening. Then I went to a second hearing for the 9/11 case in December 2015, which also had a limited media attendance. So, I decided just to keep at it. After a few trips, I started becoming hooked on the story.

LD: What hooked you into it? And what kept you interested over the last decade?

JR: At first, I was hooked by trying to understand why the case was having so much trouble getting out of the gate and gaining some traction. Then I became fascinated by the bizarre mix of issues that was consuming the case, from the substantive to the mundane to the weather-related – holding the biggest case in U.S. history on a small tropical outpost brings many challenges.

Eventually, I really wanted to see the case’s main dispute play out, which involves the admissibility of evidence following the past abuse inflicted by the CIA on the five defendants before they got to Guantanamo. The defendants confessed to their alleged roles in the 9/11 plot to FBI agents on Gitmo, but that came after three-to-four years of being held by the CIA at secret black sites. The case has had so many pretrial issues – hundreds and hundreds of legal motions – but this battle over admissibility has occupied the core of the case for much of my time covering it. That’s why it’s also the focus of the book: I attempt to explain what happens when our democracy completely removes people from the law for years at a time, then attempts to use an American court of law to prosecute them.

I attempt to explain what happens when our democracy completely removes people from the law for years at a time, then attempts to use an American court of law to prosecute them.

LD: It sounds like it really tested the limits of the rule of law in this country, and following due process.

JR: There are many opinions of the court, even in legal circles, which I’ve learned in my years talking to people about the case. People in the human rights and defense communities are often quite critical of the military commissions as a cheap imitation of American justice. But other people are amazed that we would spend so much time and effort – and hundreds of millions of dollars – making sure that the accused 9/11 plotters get such a fair case, in their view. The teams are stacked with talented professionals from the civilian and military worlds, including some of the best death penalty lawyers in the country. Clearly, by one simple analysis, they are not being railroaded in this court: The government is seeking their execution, but it has yet to even get them to a trial.

LD: Where is the case at now?

JR: The case might be in one of its greatest phases of uncertainty. Three of the defendants reached plea agreements last summer with the Pentagon official overseeing the court, known in military justice as the “convening authority.” Those deals removed the death penalty as a sentencing option and were a recognition that pleas were the surest path to finding a resolution of the case, in light of all the challenges of getting to a trial. But Sec. of Defense Lloyd Austin decided to withdraw from the agreements, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit just signed off on the legality of his decision to do so. We actually thought there was a chance we’d be publishing this book right as Mohammad, Walid bin Attash and Mustafa al Hawsawi would be pleading guilty. But those defendants will now have to return to their pretrial proceedings if they don’t successfully argue on further appeal that their plea agreements should be enforced.

Another defendant, Ammar al Baluchi, decided to not enter into a plea agreement and to instead pursue the suppression of his confessions to the FBI – in other words, taking the case’s biggest pretrial dispute to its conclusion. Shortly before he retired, the judge, Air Force Col. Matthew McCall, sided with al Baluchi by suppressing his FBI statements because of his earlier CIA torture and incommunicado detention. But the government is appealing that ruling. So his case may also be mostly on hold.

Finally, almost two years ago now, McCall found a fifth defendant, Ramzi bin al Shibh, mentally incompetent to assist in his own defense – which his lawyers blamed on his CIA torture. He’s been severed from the case, but the government will try to prosecute him again at some point. So you've got five defendants on what appear to be three different litigation paths, with the amount of forward progress on any of them very difficult to predict. And we now have a new military judge in the 9/11 case, who will be the fifth to preside over hearings.

LD: You have a history at Lawdragon of covering global justice work, in Rwanda, South Africa and in parts of the former Yugoslavia. Did that background impact your coverage of the 9/11 case?

JR: Yes, I got early experience in covering global justice issues and terrorism cases as a reporter at the Los Angeles Daily Journal, which included writing articles on the prosecutions of John Walker Lindh and Zacarias Moussaoui. In the early years of co-founding Lawdragon, I got a master's degree in human rights studies at NYU’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study that focused on justice mechanisms for mass atrocities and other gross human rights violations. In addition to my academic work, I also did journalistic articles for Lawdragon on these topics. It really did help prepare me for covering Gitmo, because I researched justice systems that were new and facing immense challenges because of the staggering crimes and tragedies they were wresting with.

I researched justice systems that were new and facing immense challenges because of the staggering crimes and tragedies they were wresting with.

I think that background has given me a helpful perspective on the Guantanamo proceedings. The system is adversarial like any other American court – and the tension in court between the two sides of the courtroom can be intense – but I often see everybody as basically stuck with the same problem, trying to work it out. They’re all dealing with the same mess. I think “America’s Trial” presents that sentiment at different points. Even in phases where proceedings go smoothly, you’re going to have many stakeholders disappointed in and even angered by the process – that’s something else I learned in my studies of other justice mechanisms.

LD: Can you talk about the access you have when covering the case on the base? You said you’ve covered each hearing in person since October 2015?

JR: Yes, and I’ve occasionally covered the other cases over my 55 or so reporting trips to the base. As I explain in the book, I’m a big fan of sitting in court, even though you are in a viewing gallery behind three panes of glass and hear the audio on a 40-second delay, which is used to prevent the spill of classified information. I think watching the whole court is better than the feed that is broadcast to the media center, which is located outside of the court complex. That feed is also shown at a closed-circuit viewing location at Fort Meade, Md. Going to Gitmo also allows for real-time interviewing of the lawyers on the case, which is helpful, though the Office of the Chief Prosecutor has had a policy of not meeting with the media since October 2017. We also meet with victim family members on most trips for on-the-record discussions.

A lot of people ask me if you can go to Cuba – unfortunately, no, we are stuck on the base. But we are generally free to move about the base on our own so long as we wear our media credentials, and so long as we are not taking photography. Taking photos or videos requires the presence of a public affairs officer.

LD: Can you tell me about the use of the opening quote? It’s the line, “This town was never intended as a permanent place, it was merely part of a centuries-long journey.”

JR: At some point early in the writing process – maybe just at the proposal stage – I came across that line late at night, when reading Ted Chiang’s “Tower of Babylon.” I took a photo of the page with my iPhone, and the next morning I typed it into an excel that contained dozens and dozens of different ideas and thoughts related to the book. Most of those ideas fizzled away but that line never left me, whether I was writing parts of the book or killing time on Gitmo, or even just daydreaming in Brooklyn. The meaning is probably self-explanatory, but I hope Mr. Chiang reads “America’s Trial” someday and explains to me what I was thinking.

LD: Do you plan to continue covering this litigation?

JR: For now, yes. The next hearing is set to start September 22, but it’s far from certain if it will actually happen or what might make its way on the docket. At some point, it will be time to walk away, but it’s also far from certain when that time will come.

"America's Trial: Torture and the 9/11 Case on Guantanamo Bay" (Skyhorse Publishing) is available now on Amazon, Bookshop.org and most other online sellers.

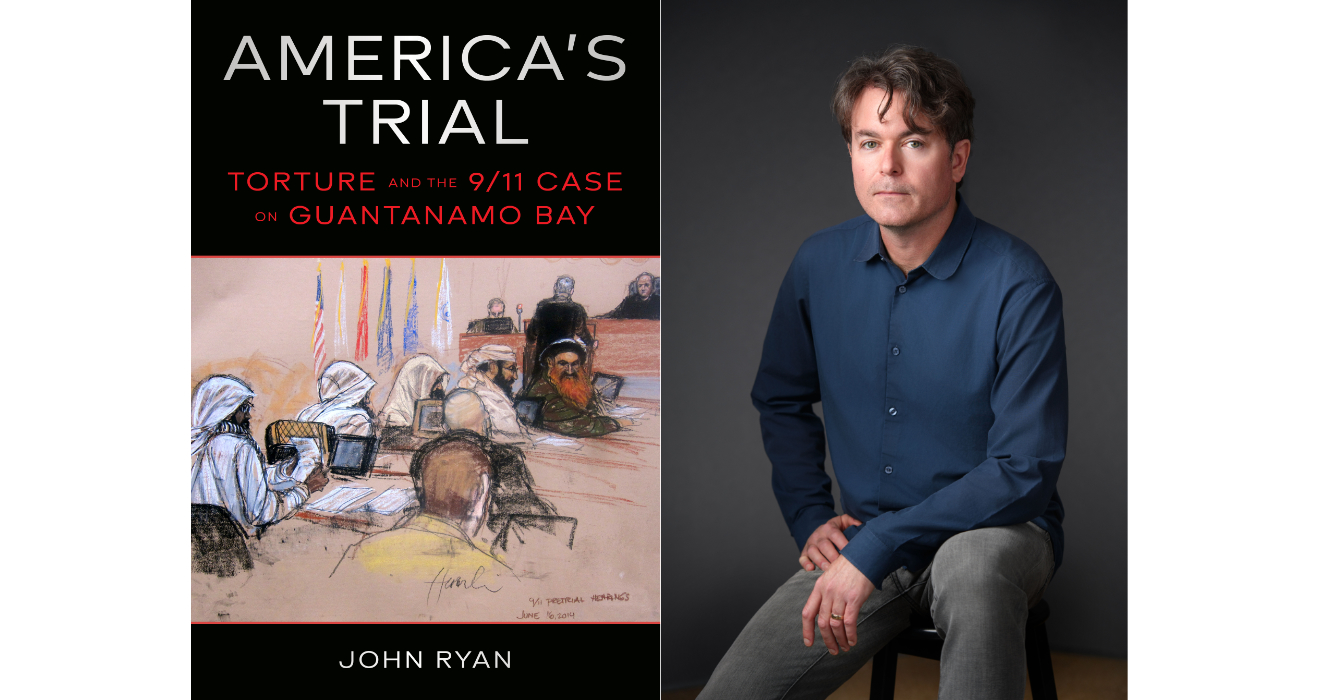

Cover design by David Ter-Avanesyan. Cover image by Janet Hamlin. Author photo by Nick Coleman.